(Originally published in Pinellas County Review, September 1994)

They call it the Oba Chandler Room.

In it, more than 75,000 documents and 300 pieces of evidence are stored, helter-skelter, in thick blue binders and floor-to-ceiling metal cabinets, all relating to the murder trial which has turned the usually quiet Countryside commercial law firm of Tew, Zinober, Barnes, Zimmet & Unice inside-out and upside-down.

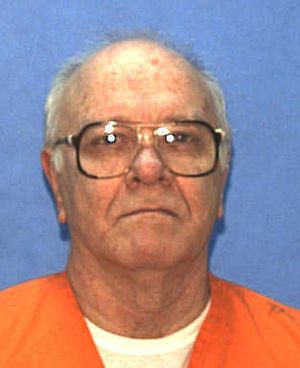

A man who has never seen the inside of this room, triple murder defendant Oba Chandler, is the cause of this tumult. Chandler is currently on trial in a Pinellas County courtroom, accused of the 1989 rape and murder of an Ohio dairy farmer, Joan Rogers, and her two teen-age daughters, Michelle and Christe. The women disappeared on June 1, 1989, while on vacation in Florida and were discovered three days later floating in Tampa Bay, their bodies bound and gagged, nude from the waist down.

Chandler’s attorney, Fred Zinober, 42, is responsible for packing this former office, as well as for dragging the firm into a case which consumed 2,300 billable hours in a year – even before Chandler’s four-week trial began on Sept. 12.

Unfortunately for the firm, it will never be able to bill its $200 per hour average rate for Chandler’s defense because Zinober agreed to accept a flat $100,000 from the state when he took on the case. It seemed fair at the time, but for those whose math isn’t strong, that’s now $43 an hour and dropping daily.

“I think, on balance, (taking the case) was the right decision,” says the firm’s managing partner, Joel Tew. “It wasn’t necessarily the best financial decision, however.”

The case promises to be the firm’s – and certainly Zinober’s – highest profile case ever. In the course of being interviewed for this story, the attorney’s secretary handled an inquiry from the Maury Povich Show. The case has already been the subject of reports on Unsolved Mysteries, Hard Copy and Inside Edition.

When Zinober, a veteran of four years in the Pinellas-Pasco Counties State Attorney’s office, joined Tew’s firm eight years ago, he was expected to become the commercial firm’s star litigator. And he has. But it wasn’t long before Zinober was itching to re-enter the criminal arena, this time as a defense attorney.

“I said, ‘Look, I really want to get back into this, just this one criminal case, let me have some fun.’ The partners said fine,” Zinober says.

Zinober took three risks eight years ago in defending John Burke, a man accused of first-degree murder. First of all, he and Larry Jacobs represented the man for free. Second, criminal defense was not in his firm’s mission. And third, he had spent the last four years prosecuting accused murderers, not defending them.

Naturally, he won the case. (And met his future wife, Dala Ann. She was the court reporter.)

“It was such an incredible rush,” he says. “Everybody said, ‘Wow, first case you’re defending, it’s a once-in-a-lifetime, you’ll never do it again.’ ”

After Burke, Zinober received permission from his partners to defend another man accused of murder. This time, he teamed with Paul Levine, now a judge. “And what do you know?” Zinober says. “The second guy was found not guilty.” So was his third client, Mark Hartsell, a man who shot a woman in the face in front of her husband and two children. He was declared not guilty by reason of insanity.

“I’m a trial lawyer, I’m not a criminal defense lawyer,” Zinober says. “I do this, quite frankly, more as a hobby to keep myself sharp and because I love it. I love the fight. And I love going to trial.”

Michael Hayes, an attorney in the Washington, D.C. firm of Dow, Lohnes & Albertson, recently worked alongside Zinober as co-counsel for Cox Enterprises in a civil matter.

“Fred is tenacious, intelligent, creative – a wonderful guy to work with,” Hayes says. “Trial lawyers have a perverse side to them in that they like a good fight. It would be a challenge to be on the opposite side from Fred.”

Outside of the criminal realm, Zinober has also helmed several high-profile civil cases, including a concerned citizens group supporting former St. Petersburg Police Chief Curt Curtsinger’s attempt to get his job back after being fired. Later, when Curtsinger ran for mayor and lost, Zinober unsuccessfully challenged the results of the election.

Ironically, many of the police officers he represented in trying to return Curtsinger to police chief are now detectives working to convict Oba Chandler in the Rogers triple-murder. It’s a challenge he anticipates with a certain glee.

“Cops are pretty good,” Zinober says. “They respect you if you beat them. They’re tough, and if you can beat them or be tough against them, they’re the kind of guys that when they’re in a jam, you’re the kind of guy they come lookin’ for.”

Certainly he enjoyed a better relationship with the police when they both worked the same side of the legal fence. For instance, as lead trial assistant for the state attorney’s office, he and Jim Hellickson (now working against Zinober on the Chandler case) prosecuted Richard Rhodes. He’s on death row now, convicted of strangling his girlfriend in downtown Clearwater’s old Edgewater Hotel just before the hotel was demolished and the debris removed to a local gun club. Several weeks later, Rhodes’ girlfriend was discovered, her body badly decomposed. The prosecution’s case was made on “very meticulous circumstantial evidence,” Zinober says.

“I get really fascinated by circumstantial evidence cases,” he says. “(In the Rhodes case,) we got an anthropologist from the University of Florida to reconstruct how the bones were broken. See, the cause of death was strangulation. You had a body that had decomposed for 3-1/2 weeks. The bones had totally been crushed because they brought the backhoes in to demolish the building. We reconstructed the cause of death as manual strangulation because the hyoid bone – this little bone underneath your jaw – was broken. And even though every other bone in her body was broken, the only way that one could have been broken was by manual strangulation.”

The tale of Zinober’s dissection of the Rhodes case doesn’t end there, though.

“I get into these things,” he says. “(Rhodes and his girlfriend) were last seen in a bar by the bus station. That was the last time she was seen alive. Well, I wound up dressing down one day and walking around the seedier part of town, going in and out of all the bars, seeing what things were like, reliving what these people were going through to get a sense of what really happened. Had a few beers, talked to the people. Not doing any investigating, just trying to get a sense of ‘what would it be like?’

“When you’re trying a case,” Zinober says, “what you’re trying to do is reconstruct everything to the jury. And the best way you can do that is be a part of it yourself. It’s easy to get them to picture in their mind what happened if you can picture it in your own mind.”

He put this notion into practice again for the Chandler case. When depositions needed to be taken in Orlando, Zinober stayed in the same hotel where Joan Rogers and her daughters spent their last night before driving to Tampa.

“I got a sense of, this was the last place they had been before they came to Tampa and were killed. What is it that they saw? It’s kind of like you’re living a true crime novel,” he says. “You read through all these reports – I can’t put them down. ‘Well, what happened next? What did they do next? What did they see?’ ”

When he’s not working a murder case, Zinober usually has his nose buried in true crime books. His tastes run to Vincent Bugliosi and Joe McGinness; he also enjoys John Grisham’s works of crime fiction. He and Jim Martin, Clearwater lawyer and fellow veteran of the state attorney’s office, recommend books to each other.

“Jim made a good comment. He said, ‘The true life situations are so much more interesting than fiction.’ Which is true. If anybody wrote these things and said it was fiction, you’d say, ‘This could never happen.’ But when you read the police reports, you go, ‘Gee, whiz, this really did happen.’ And it’s even weirder than somebody could write about.”

Along the lines of switching from fiction to non-fiction, Zinober says the jump from criminal prosecutor to defender wasn’t as difficult as he imagined. He credits his ease with the two years he spent in New Hampshire in private practice before joining the state attorney’s office in 1982.

“When you’re a prosecutor,” Zinober says, “you see (crime) from the victim’s perspective and the defendant is kind of an impersonal name, a file. When I left the state, I was one of these guys who said, ‘I’ll never represent a criminal.’ I said, ‘Joel, I don’t have any desire to represent any of these dirtbag criminals. Don’t worry about it.’ But criminal law is in your blood. And I kind of eased into it because of the first guy I represented, John Burke. I was totally convinced that this was the aberration. This guy was getting screwed and he needed me to protect him. I’d always been real good on protecting other people. Then the more I talked to people I felt well, what they’re saying makes sense. Maybe the way the evidence looks isn’t right. Maybe there’s a reason the evidence looks the way it looks. When you start actually meeting these people and defending them – and some of them have even done some really kind of screwy or bad things – I don’t have a problem with it at all.”

That might disappoint James T. Russell, the long-time state attorney for the Sixth Judicial Circuit, who hired Zinober as a prosecutor in 1982.

“Mr. Russell has always been like a father to me,” Zinober says. “I mean, I’ve gone my rounds with him, too; I’ve been yelled at more than once by him. Russell was just a brilliant guy. Tough, fair – he ran that office the way that office should be run. I missed my own farewell party because I was in Russell’s office till 8 o’clock talking about the Bears and the Giants. He was that type of guy.

“One time, we were prosecuting a guy by the name of Athanasio John ‘A.J.’ Maillis,” Zinober recalls. “A.J. had been probably the No. 1 confidential informant in the history of the CIA for Operation: Grouper, this big thing they had in the Bahamas. When he got out of the CIA, he wound up being one of the top cocaine traffickers in Tarpon Springs. Russell warned the federal government: Put the wraps on this guy. The intelligence on this guy was A.J. was doing a lot of coke. Russell kept saying to the feds, ‘Get this guy out of here or get him under control!’ They wouldn’t do it. So finally Jimmy said, ‘I’ve had enough of this shit.’ The sheriff’s department made a case. It was a tough case, two keys of coke. Beverly Andringa and I prosecuted the case. The CIA was not happy, the federal government was not happy. They sent some people down to see if there was something that could be done and we said no. Then somebody pretty high up in the CIA came down and we had a meeting in Russell’s office. Everybody else had this fear of the CIA. Russell just sat there. I’ll never forget him looking at the CIA people and he unleashed on them like he used to unleash on us when we screwed up. He said, ‘You people have forgotten where your responsibilities lie! You put this drug trafficker in my community and now you have the nerve to come down here and complain?’ He blew them over.”

The opportunity to defend Oba Chandler came in a phone call from the judge in the case, Susan Schaeffer, last October.

“I had heard it was this massive case,” Zinober says. “I had heard about ‘The Wall,’ the euphemistic expression for the wall of reports down at the St. Petersburg Police Department. I heard that it was an overwhelming amount of paperwork. Now, paper doesn’t scare me as much as it might a normal criminal practitioner because in commercial work, I’m used to paper. I knew it was going to be a lot of work. I don’t think I knew how much work it was going to be.”

Zinober discussed the case with the three attorneys who preceded him, public defender Ron Eide and criminal defense attorneys Tom McCoun (now a judge) and Bob Dillinger. Then he appeared once more before his partners, seeking their counsel and support.

Partner Andy Salzman said, “This is one of those cases that may come along once in your life. The question is, do you let it go by?”

Zinober, a film buff, answered by recalling Ann-Margaret, of all people, in Grumpy Old Men. “Ann-Margaret said, ‘The only things in life you regret are the risks you don’t take,’ ” Zinober says. “Which is true.”

The firm – not without its share of dissenters, admits Joel Tew – agreed to support Zinober one more time. “There was a disagreement among the partners as to whether it was something we should get involved with,” Tew says. “But everyone has since pulled together and supported Fred in this.”

Very little work had been done when Zinober finally cleared his desk and began on Chandler’s case in earnest last April. By August, he was so focused on the case, the rest of the world just slipped away.

“I’m the type of guy who will put milk in the cupboard,” he says. “I’m not allowed to drive when trials are going on, people have to drive me around. I focus around the clock. I’m thinking of this case all the time. I dream about the case. My wife is sick of me thinking about nothing but this case.”

His work habits at the height of a murder case are maddening, not just for his family but for the 14 lawyers and other employees of his firm. “He expects the people who work with him and for him to be the same way he is,” Tew says. “And he’s liable to show up at 2:30 a.m. to work. He dreams it, eats it and sleeps his practice. We just leave him alone and let him do his thing. He couldn’t change if he wanted to. That’s Zinober.”

Dala Ann Zinober, his wife, wasn’t initially thrilled with his choice of client, this time around.

“Let me put it this way: my wife understands,” Zinober says. “At first, I have to admit, she was a little bit concerned about this. She said, honestly speaking, ‘Gee, Fred, do you really want to take this case?’ But she sees how I feel about it and it gives her some pause. I’m fortunate in that she’s been through the court system. She’s a court reporter so she understands. She’s a very conservative person, the type I would not want to have on a jury if I were defending somebody.”

Order ‘Death Cruise’ by Don Davis from Amazon.com by clicking on the book cover above!

Zinober says his client has been “very easy” to work with. More importantly, Zinober – despite 17 witnesses who say his client confessed the murders to them, plus physical evidence – believes he has a winnable case.

“Oh, absolutely,” he says. “No question about it.”

Would he have taken it even if he wasn’t convinced it was winnable?

“I doubt it,” he says. “Quite frankly, the challenge was one of the reasons I took it in the first place. And if I didn’t feel it was a winnable case, that challenge wouldn’t have been there. There’s no question in my mind this is a winnable case. It’s not an easy case. At all. Sometimes I feel like I’m fighting the Russian army with a water gun. But I’m not afraid of that.

“I’m here to defend a guy’s life. But sometimes it seems everywhere you turn, people are looking to knock you down. You have people saying, based on what they read in the newspaper, ‘How can you defend this man?’ The press – my case is getting hammered in the press. Sometimes you just feel you’re fighting everybody.”

His partner, Joel Tew, says it’s not hard to see why Zinober feels this way.

“Based on the number of prosecutors working against him, frankly, Fred needed an O.J. Simpson team with him,” Tew says.

Instead, he has two part-time investigators and two paralegals.

“Sometimes it feels I’m fighting insurmountable odds,” Zinober says. “Sometimes I feel like I’m some ‘Man of La Mancha.’ I identify with a guy going up and fighting a windmill. It’s an awesome responsibility. You’re the one, in the end, people look to. If he winds up suffering the death penalty, you’re the one questioning yourself for the rest of your life. ‘Have I done everything? Did I make sure the guy got a fair trial?’ ”

Order ‘The Profiler: My Life Hunting Serial Killers and Psychopaths’ by Pat Brown with Bob Andelman, available from Amazon.com by clicking on the book cover above!

BAY LAWYER FILE

Name: Fredric S. Zinober

Title: Attorney; Tew, Zinober, Barnes, Zimmet & Unice

Birthplace/date: August 2, 1952, Queens, N.Y.

Spouse’s Name/Occupation: Dala Ann Zinober, court reporter

Children: Tina and Luke Chaffin, 17 (twin step-children); April Lynn Zinober, 4

Pre-Law: “My father was editor of an automotive magazine in New York for 30 years, and my mother is an elementary school teacher. My primary pre-law activity, outside of academics, was sports. I was a linebacker on my college (Middlebury College, VT) football team, and was an infielder/defenseman on the lacrosse team.”

First Law Job: Clerked for Rockville, MD, attorney Charlie Shaffer before graduating from Catholic University of America Law School in 1980

Subsequent Career: Associate, Cleveland, Waters & Bass in Concord, NH, 1980-82. Hired as assistant state attorney by Pinellas-Pasco prosecutor James T. Russell. Joined Tew, Zinober, Barnes, Zimmet & Unice in 1986.

Biggest Victory: “The not-guilty verdict by reason of insanity in the Mark Hartsell case. Prior to this, it is my understanding that it had been over a decade since a man was found not guilty by reason of insanity on a first degree murder charge at trial.”

Biggest Disappointment: “Every loss I have ever had is equally disappointing.”

Lawyers Most Admired: Albert Krieger of Miami; Bobby Lee Cook of Georgia; Terrance McCarthy, federal public defender of Chicago

Favorite Law-related Book: Blind Faith by Joe McGinness

Favorite Non-law-related Book: Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoevsky