Before her, Cornelia Corbett’s team, the Tampa Bay Rowdies.

Behind her, a few thousand exuberant soccer fans who haven’t given up the dream.

There isn’t much to cheer on this overcast Sunday night at Tampa Stadium except that the rain has stopped. Despite the Rowdies having advanced to this American Soccer League playoff game against the Boston Bolts, only 5,000 people have come out to support the team. Even their loudest screams echo as but a whisper in the cavernous bowl, where 67,000 seats both end zones and the entire north side of the field are empty. Even the concession stands are against the Rowdies tonight; they ran out of hot dogs before halftime.

Still, Cornelia Corbett is unswayed. Watching the entire game in her now familiar position on one end of the bench beside head coach/general manager Rodney Marsh, the owner of the Rowdies concentrates her energies on the field. She winces each time the Bolts score and claps enthusiastically when the Rowdies engineer an elegant pass or steal.

The Rowdies are down two games to none after losing two straight in Boston. This game is their last gasp and before the night is over, they will have choked, 2-1.

Despite all these clouds, there are rays of sunlight for the oft battered Rowdies. Their regular season record was 12 wins and 8 losses, up from 10-10 in 1988. They won their division. An average home attendance of 5,792 was actually tops in the two-season-old American Soccer League. And while the team may lose up to $200,000 for its fiscal year (overhead from the off-season includes a reduced office staff, soccer clinics for youngsters, player tryouts, travel and league work), it actually showed a small profit of $10,000 during the team’s 20-game season.

That’s why Cornelia Corbett is smiling.

“I think we’re making headway,” she says. “Our losses aren’t as bad this year as last. It’s a minute swing: it’s possible we could make $150,000 and it’s possible we could lose $150,000.”

Corbett doesn’t know that the Rowdies ever made money not under founder George Strawbridge in the North American Soccer League (NASL), nor under the ownership troika of Stella Thayer, Bob Blanchard and Cornelia’s husband, Dick Corbett. In the heady years of the NASL, when Marsh was a star player, Gordon Jago was coach and a coterie of international stars electrified the league’s games on national TV, the Rowdies averaged 28,000 fans at Tampa Stadium. There was tremendous overhead associated with that success. But it’s a level Cornelia Corbett would like to reach. “I can’t imagine drawing an average of 28,000 and losing money,” she says.

Sportswoman, socialite, businesswoman, wife, mother of four who is Cornelia Corbett?

“She’s a mover and a shaker in our sport,” says Colin Phipps, owner of the Orlando Lions ASL team. “The average sports enthusiast sometimes gets enamored of the sport and forgets the practicality. She understands both.”

“She understands sports, which is a major plus for any owner,” says Rodney Marsh.

Born in Manhattan in 1946 to a “well-to-do” family (she’ll say only that her father is in “investments,” her mother owns racehorses and Cornelia herself has “private income”), Corbett earned a degree from New York University (Washington Square) in history. As soon as she graduated though, “Cornie” as friends and family call her went west to teach skiing in Aspen. She met Dick there in ’68 and returned with him to New York City. They married two years later.

The honeymoon was exotic and long three months of hiking and wandering through Tibet, Nepal, Kamandu and the Himalayas. “The two of us slept in mud huts with the Nepalese,” remembers Dick. “We traveled with nothing but the clothes on our backs and two sleeping bags. That trip showed she was a great outdoors lady. Leaving Manhattan, she was comfortable sleeping in a mud hut next to a campfire, crawling up and down the Himalayan range. She was a doer and great fun to be with.”

As her husband made his first million in real estate (see sidebar), Cornelia spent three years as a case officer investigating abuse and neglect for the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children. “It was interesting and pretty gruesome,” she recalls. When their first child was born in ’73, it was time for a career change. “I could no longer be objective,” says Cornelia. “I couldn’t do case work. Every child became my own.”

The Corbetts met on the ski slopes, but Dick himself a former light-weight amateur boxer with a nose broken in six places to prove it introduced Cornelia to golf and, of course, she’s been playing ever since. They take family vacations to hunt or go white-water rafting in Colorado, climbing in the Grand Canyon and camping with Wild Kingdom TV host Jim Fowler (he is godfather to one of their children). The couple is “simpatico,” says Cornelia, very upbeat.

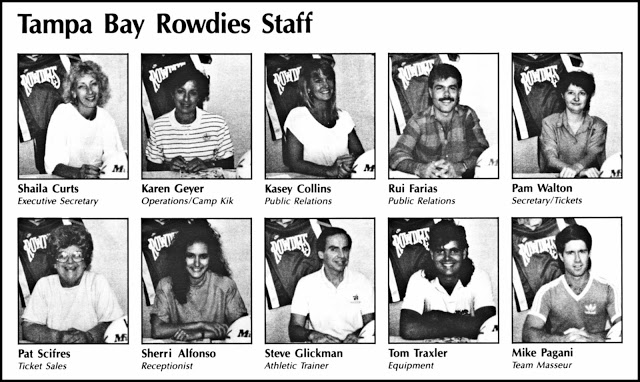

1989 Rowdies Staff

If an impression of Cornelia Corbett as ultimate sportswoman is being formed, it’s not incorrect. “I’ve been a sports nut all my life,” she says. “If I have been consistent in one thing in my life, it’s my love of sports and competition.”

Cornelia and Dick moved to Tampa in 1978. In 1984, when the NASL went under, Dick Corbett’s partners in the Rowdies, Stella Thayer and Bob Blanchard, decided to bow out as well. They didn’t know where soccer was going if anywhere and lacked the spirit and time to continue. Dick and Cornelia toughed it out although the team has nowhere to play in ’85. In ’86, Dick made his wife sole owner.

“As he has done many times in the past,” recalls Cornelia, “he said, ‘Do you want to see what you can do with it?'”

No hesitation; she said yes.

Corbett had worked in the Rowdies front office during the last NASL season, so she knew the makeup of the business. The game itself was close enough to field hockey which she played competitively from grade school through college to assure her of competency in the finer points of soccer gamesmanship. And, most of all, she is not a woman to shirk from a challenge. When Dick needed someone to supervise a brownstone gutting and renovation in New York City back in the early days, he turned to Cornelia to bring in estimates and run roughshod over the crews. When he was in-between general managers at the old Hall of Fame Inn, Cornelia effortlessly handled the job.

“I’ve stepped into gaps for him a lot of times as a caretaker,” she says matter-of-factly.

In the case of the Tampa Bay Rowdies though, what Corbett inherited from her husband was very little. A familiar nickname, one that was once synonymous with having a good time. A somewhat tired Irish melody and phrase “The Rowdies arrrrrreee …. a kick in the grass!” Westshore offices in need of repair and a fresh coat of paint. Those were just the peripherals: the team itself had disintegrated with the league. There were no players, no coach. And no league to play in.

Desperate and choiceless, Corbett entered the Rowdies in the American Indoor Soccer League. The team played indoors at the Bayfront Center Arena. Despite a 21-21 record and a playoff berth, fans knew this was not the old kick-in-the-grass and they stayed away in droves.

The 1987 season was the first to offer promise to soccer fans. Corbett entered the Rowdies in the start-up American Soccer League (ASL) and quickly found herself the Grand Dame of the game, having had as much or more experience than most of the other owners in the 10-team league. She was called upon for opinions and rose immediately to the league’s executive board. The Rowdies’ first season in the ASL was a flat 10-10, but the team led the league in attendance.

Rodney Marsh runs the game side of the Rowdies; Cornelia Corbett handles the business. She says, contrary to public opinion, husband Dick is completely out of the team’s operations.

Finding a woman running a professional sports franchise is still unusual. Marsh says male team owners around the league found they had quite a capable associate in Corbett, however someone who knew their business better than they themselves did.

“There are a lot of ethnic owners in soccer and many of the meetings get personal,” he explains. “She comes in with a very cold, calculated, detail-oriented business concept. They were a little overpowered by that.”

Roy Wegerle, Tampa Bay Rowdies, 1989

Linda Powell, director of operations for the American Soccer League, says Corbett has earned the respect of her counterparts. “She’s been in the sport longer than most of the owners,” according to Powell. “She is very concerned that the franchises run professionally and that her colleagues also run their franchises professionally.” Corbett was chair of the league’s marketing committee at one point and currently sits on the executive committee.

“Our club is as professional an organization as you can have,” reiterates Marsh. “We are in the lead at everything we do, whether it’s player salaries, medical care, uniforms, stadium and travel arrangements. It’s a real first-class organization.”

A first-class organization maybe, but operating on a shoestring.

Corbett runs a very lean operation. In-season, the Rowdies only have 10 full-time employees. The league has a player salary cap of approximately $75,000 an average of $250 per game, per player which controls costs and quality. Many players have second jobs which sometimes interfere with practices and even games, but in a nickel-and-dime league, the Rowdies cope.

Off-season, players receive no pay and the administrative staff is reduced to a bare bones four. “We’ve got a lot of people who are very loyal,” according to Corbett. “Our receptionist, Pat, has been with the team since 1975. Every August (when the soccer season ends) she says, ‘See you in January.'”

To reduce stadium costs, Corbett has explored playing in a smaller facility. A more intimate, contained facility would also boost morale and give the impression of fewer empty seats. The Florida Suncoast Dome has been discussed, partly because soccer youth leagues and Rowdies fan support has always been greater in Pinellas County than Hillsborough, but the team has objections to the artificial turf planned there.

ASL administrator Powell says none of the teams in the ASL are profitable yet.

“We told people when they came in: Don’t expect a profit in two years,” she says. “One of the goals of the league is to keep losses minimal. This is a growth industry; we are still growing. There is going to need to be an upgrading where we can pay players a living wage and keep them with the teams. Then we can build them up within the community.”

When the Rowdies were a bigger deal to the Tampa Bay sports public, the team began a commitment to building soccer in the community through youth leagues and summer camps. While times are tough now for the professional team, amateur soccer in the Bay area is thriving so the Rowdies have maintained their efforts with teen-agers. By operating clinics for the kids featuring Rowdies players and by offering deeply discounted season tickets to youth soccer league members, the team hopes to develop a new generation of loyal fans who will grow with the Tampa Bay entry in the ASL.

“We’ve instituted a program where, when kids join their league, we offer them a $10 season pass that will allow kids to get in for $1 a game,” says Cornelia Corbett. “We are trying to reach out and give the benefit to the kids who play the game. We’re working closely with all the youth leagues.”

The athlete in Corbett sympathizes with Tampa Bay area youths who need more places to play amateur soccer.

“The need for fields in unbelievable,” she says. “Your senior divisions can rarely find fields to play on. I get discouraged the United States has more soccer players than any other country, more than England, Brazi, Argentina, Germany. And yet the facilities aren’t there. In Tampa Bay alone there’s 20,000 kids playing the game. To me, politically, you multiply that by moms and dads, that’s quite a political force.”

Donna Salzer is administrator of the Florida Suncoast Soccer League and state registrar for senior division soccer players. She thinks Corbett’s vision of a brighter day for soccer in this country is accurate.

“The group born in the ’60s is going to make soccer American,” says Salzer. “When they have children, they will grow up with soccer. I’m close to 50. Our generation didn’t get introduced to soccer until their 30s. My son is 21 he’s played for 15 years. He goes to all the Rowdies games and can relate to it. We have to allow these kids to grow up. Soccer is going to catch on.”

As Corbett and the entire league waits for the next generation of fans to mature, they are faced with other stumbling blocks before the American public can be expected to open its arms to this very European sport. Soccer needs television exposure and knowledgeable, colorful announcers to bring it to life and explain the nuances. A likely merger with the Western Soccer League in 1992 could create new media opportunities. But this is a low-scoring game so fans need to be trained to appreciate the action and defense. And there is nothing like an eclectic, talented player to add a little zing to the field of play. Pele brought it from Brazil and Franz Beckenbauer brought it from Germany to the old NASL. The Rowdies of old had three players Marsh, Tatu and recently retired Steve Wegerle who could charge up a crowd.

None of this is news to Corbett or Marsh, of course.

“It’s a Catch-22,” says the team owner. “Soccer will not succeed without mass media. Media will not get involved until there’s 10,000 people in the stands.

“I also think the quality of the product (was better) in the late ’70s,” she continues. “We had a lot of Europeans coming over. Now you can only play two visa players. I know how fickle the American fan is it would be lovely to have a charismatic hero. I never saw Rodney play but I did see Tatu. Tatu did terrific things and he would score. You can play to the crowd when you can back it up with ability. I just don’t think we have Americans with the personality and confidence to do that.”

“You have no argument from me,” says Marsh. “For any sport to succeed, the quality has to be there. What is quality? Star players.”

Marsh also notes the inconsistency that has developed in fan support between the Rowdies and Tampa Bay Bucanneers football team.

“We had a seven-game winning streak a team record. We ended 12 and 8 and we still had 5,000 people. If the Bucs did that, they’d have 72,000 people in the stands. We need to have a winning season to maintain our crowd. The Bucs need to have an ordinary season to improve their crowd.

“At the end of the day,” concludes a hopeful Marsh, “soccer in this country will be enormous. Staggering. But whether or not that will be in my lifetime, I don’t know.”

There are precious few women in ownership positions with professional sports franchises. Cornelia Corbett is one; Marge Schott of the baseball Cincinnati Reds and Georgia Frontiere of the football Los Angeles Rams are the only others.

You can bet neither Frontiere or Schott is working indefinitely without salary or income from their teams as Corbett does.

Equally as rare in professional sports are owners who watch their teams compete from the players’ bench the way Corbett does. Home or away, her players know she’s going to be seated beside them from the opening buzzer ’til time runs out.

“It is very difficult to be in an owner’s box when family is there and you’re entertaining guests and friends to really be able to watch the game without offending someone,” according to Corbett. “Also, I find for me you’re quite removed when you’re high up. I prefer to be close-up. Corbett arrives at Tampa Stadium for 8 p.m. home games by 6:30 p.m. She’ll check in on the owner’s skybox, the V.I.P. and media boxes. Then she tours the stadium, checks the placement of sponsor banners on the field and visits the entrance gates for a fix on attendance. Last stop is the visiting team’s lockerroom. “If there’s any trouble-shooting or decision-making to be done, I’m available,” she says. “But by ten of eight game time I move down to the field.”

She says that sitting on the bench evolved from road trips with the team. “Where else are you going to sit and totally concentrate?”

It would be every armchair quarterback’s in this case, armchair goalie’s dream to sit on the bench of a favorite team and shout encouragement and advice. Corbett knows she walks a fine line between being a knowledgeable, influential fan and being considered an interfering, know-nothing, rhymes-with-rich.

“You have to restrain yourself,” she says. “I don’t think it’s the owner’s place to be coaching, making comments, or trying to second-guess your coach.”

During the Rowdies-Bolts playoff game, Coach Marsh frequently whispers to Corbett, who sits beside him, describing finer points of the action or simply expressing his frustration. After just a few minutes of observing the two, it becomes obvious that just because he is seated beside his boss and a lady at that, Marsh and his players do not weigh the invectives they sometimes spew at referees and players.

During the Rowdies-Bolts playoff game, Coach Marsh frequently whispers to Corbett, who sits beside him, describing finer points of the action or simply expressing his frustration. After just a few minutes of observing the two, it becomes obvious that just because he is seated beside his boss and a lady at that, Marsh and his players do not weigh the invectives they sometimes spew at referees and players.

“The players on this team have shown enormous respect by treating her the same way they’d treat anyone else,” says Marsh. “It’s almost like she wasn’t there; they treat it normal. I’m pleased they do that. I’d hate for them to be looking over their shoulders.”

‘

Close quarters during the heat of battle has helped Corbett come up to speed on the game of soccer and given Marsh the full confidence of the boss. The two from all appearances share a mutual trust and working relationship. It’s also a teacher/pupil relationship at times, with Marsh the teacher, Corbett the pupil.

“Over the last three years,” confirms Marsh, “she’s really digested a helluva lot. Her understanding is very complete.”

“I ask Rodney to keep me informed about players, but as general manager, he makes those decisions,” explains Corbett. “We might discuss it so I understand his reasoning, but it’s never to overrule him. It’d be pretty stupid of me to second-guess Rodney Marsh. There’s a very clear delineation. He knows me well enough to know when I ask a question, I’m not questioning him, I’m looking for information. After two seasons, I don’t ask as many questions as I used to. I’ve come to understand how he thinks and the quality a certain player brings.”

There must be less stress-inducing things a bright, active woman like Cornelia Corbett could do besides operating a money-losing, under-attended soccer team, right?

“I love it,” she answers defiantly. “How can you not love it? You’re involved with something you love to do, sports. And steep it with a firm business policy. For two hours on a Saturday or Sunday, I have the passion that sports take. But Monday through Friday, during business hours, it runs as a business.”

How Florida’s Pro Soccer Teams Fare

Team, ’88 home attendance, ’89 home attendance

Tampa Bay Rowdies, 55,130; 57,922*

Ft. Lauderdale Strykers, 53,580; 43,073

Orlando Lions, 27,100; 27,614

Miami Sharks, 11,620; 8,164

* Tampa Bay holds the single-game attendance record, 19,211, on July 4, 1989.

Statistics provided by the American Soccer League.

Sidebar:

Dick Corett’s International Dream

Development deals can take a long time to work out. There’s land acquisition, financing, permiting, sales and marketing. Not to mention 95 percent luck.

Even so, Dick Corbett’s International Plaza a 135-acre, mixed-use project planned at the intersection of Westshore Blvd. and Columbus Drive near Tampa International Airport has been a long time coming. First announced in 1983, the property received its DRI in 1985. Corbett has made little visible progress since, except for demolishing the Hall of Fame Inn, which was once on the site.

“It’s moving more slowly than I would like, frankly, because of the softness of the office and hotel market,” he says. “You’d like things to happen tomorrow. Developers would like things to happen today. But the frustrations of the permiting process in the state of Florida requires a lot of patience.

He says the speed of development is about to shift to a higher gear.

“My first step was to build off-site roads,” according to Corbett, who describes the current $4-million widening of Spruce Street/Columbus Drive as a joint effort between the city, state, Metropolitan Insurance and International Plaza. “Patience and prudence has been a good policy in this case because the off-site roads should be completed first so you have good access. This is an example of good planning. Once roads are in place, things will happen quickly.”

Construction will be completed in March; around that time Corbett expects to break ground for interior site work. Build-out is expected to be fully completed by 1997.

Building in Tampa is nothing like what Corbett was used to after two decades in the Manhattan real estate business. “It’s not at all the way it was when I was in New York, where things would happen quickly,” he says. “You would make decisions and have things done within 12 months. There you had tax abatement, tax incentives. The city would offer developers incentives to build. They helped make business happen. It was a strong, pro-business attitude.”

Dick Corbett has had what many would call a charmed life of being in the right place at the right time, meeting the right people and saying the right things.

He was president of his senior class at Notre Dame in 1960, the spring presidential candidates John F. Kennedy, Richard Nixon, President Dwight Eisenhower and a future pope all spoke to students. Corbett says he was fortunate to meet and introduce all four “it was an incredible year.” Kennedy had the most powerful affect. Corbett changed his career plans, joined JFK’s campaign and was a manager based in Chicago.

Kennedy’s November victory brought a young Corbett into the White House to work in congressional relations. He helped pre-screen other potential political appointments. While this was an education in and of itself, he decided to return to school in 1962 and earned an MBA at Harvard.

With a no doubt impressive Rolodex of contacts and an equally impressive resume, Corbett found a position with Joseph P. Kennedy Enterprises in Manhattan. He spent a decade with the Kennedys, buying and selling real estate, making more contacts and setting up lucrative deals for himself on the side. During that time he hit the campaign trail with Robert F. Kennedy; “I was eight feet away from RFK when he was shot,” says Corbett, pausing. “At that point, I left politics.”

Corbett says he left Harvard in ’64 with $5,000 in debt. Six years later, through shrewd real estate deals, his net worth was several million dollars. — Bob Andelman