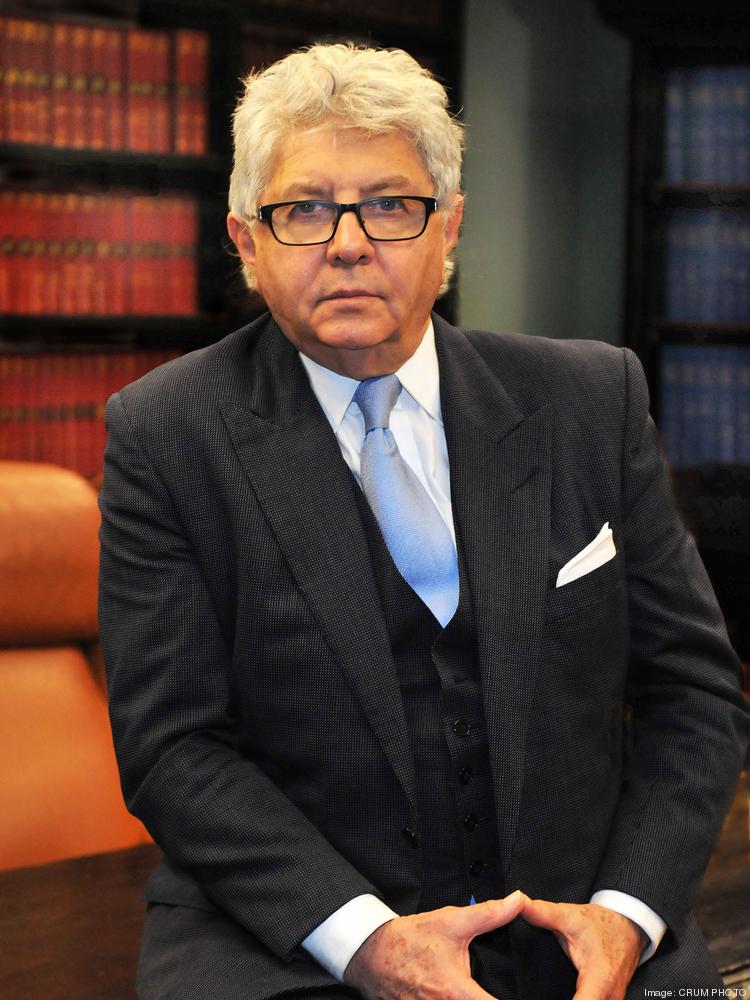

(NOTE — Even when I knew he was ailing these last few years, I somehow expected my friend Barry Cohen to live forever. So when word came on Saturday, September 22, that he had succumbed to leukemia at age 79, it was a little hard to believe. I first met Barry in 1991 when I wrote the profile below. The next time I was in his office, my mind was blown as big as the enormous poster he made of this story; it greeted every visitor to his office for years to come. It was the beginning of of an acquaintance of many years that included several more interviews, co-authoring a book that ultimately never was finished, and lots of offers to use his Tampa Bay Rays box seats. I know Barry had lots of friends, which was why it took me years to accept that he thought of me as one of them. As recently as this past year, he dropped me a note and said, “When are we going to finish the book?” I only wish we had. One more thought: I always told my wife that if I ever got in legal trouble, there was only one call to make: “Call Barry.” Rest in peace, old friend. — Bob Andelman)

By Bob Andelman

(Originally published in Tampa Bay Life, Winter 1991)

Many people see Tampa attorney Barry Cohen as an arrogant, criminal defense mouthpiece who trods through the courts much the way Godzilla toured Japan.

But not Jim and Nolia Hunter.

They turned to Cohen when their 18-year-old son, who is black, was accused of raping a white girl. Cohen was the third attorney to represent the young man, but the first to connect with both the case and the family.

“I haven’t seen any lawyer that could do what Barry Cohen did for us,” says Jim Hunter. “They wouldn’t have had the feelings or the patience. He did his homework; he did everything right. He kept my son from having a nervous breakdown. He let my son know he believed in him. He went the extra mile.”

Cohen invested months getting to know the Taylor family, getting to know their son as a human being, not a defendant. When the time came, he won quick acquittal for the Taylor’s son in a jury trial; the all-white jury needed only 40 minutes to return a verdict of not guilty.

When it was over, Cohen encouraged the young man to go to college, which he did. Because the Hunters did not have the resources of a wealthy chiropractor, Cohen allowed them wide latitude in paying his bill.

“He left his mark,” says Jim. “I think everybody should know about Barry Cohen.”

“Perry Mason can’t light a match to him,” adds Nolia.

o o o

Barry Cohen is one of the best criminal defense attorneys money can buy in the Tampa Bay area. He is our Ellis Rubin, our F. Lee Bailey. His court appearances attract other lawyers to the gallery as spectators; his unconventional, bump-and-grind legal maneuvers are the stuff of legend.

“He’s not just a Cadillac. He’s a Rolls-Royce,” says friend and fellow attorney Bennie Lazzara Jr. “If people can afford it, (they) drive a Rolls-Royce. It’s a fine car.”

As automobiles go, Cohen himself drives a gold Porsche. He’s earned it and more, with fees estimated in the legal community to be at the top of what criminal defense attorneys can earn on Florida’s west coast. Still, the car is his only visible sign of opulence. He lives in waterfront Redington Beach condo and dresses nicely but is no trendsetter, preferring jeans or sweats and a T-shirt whenever decorum allows.

Personally, Cohen is at once charming and defensive, funny and brilliant. He’s the kind of uncomplicated guy with whom it is easy to feel comfortable and share stories, yet a lifetime might not be enough to see his true self revealed. He’ll answer every question put to him, but he has a politician’s gift for answering with a deflecting question instead of an answer. And given the chance to ask the questions, he is innocent, curious and unrelenting. “Why?” “What do you mean?” “When?” “Who said that?”

Friends in the legal community suggest he is less a naturally gifted jurist than a bulldog in the legal stacks with a tremendous memory and a private eye’s sense of intrigue.

Of course, he sees himself as possessing a brilliant legal mind.

“I wanted to be a lawyer as far back as I can remember,” says Cohen, who used to skip classes at Plant High School to attend jury trials. “I remember seeing great lawyers and feeling someday, when I grow up, I’m going to be like them.”

In his own mind, Cohen would rather work out of the limelight. But in reality, he seeks it out as often as it finds him.

“He’s a colorful person by design,” says George Tragos, president of the Florida Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers. “Everybody’s got their own method of marketing and his is to be colorful.”

Cohen is probably hell to work for, although his first wife keep his books through much of their marriage and last year he married his office manager. He is always in the middle of a controversy, everything is an emergency and everyday life with and around him is chaotic. During the months of research spent on this profile, Cohen went through three personal secretaries. Former employees say only those with tough hides and extraordinary resilience survive the Cohen rollercoaster for any length of time.

“He’s the first guy there to commend you if you do a good job,” says one, “and the first to chew you out if you screw up. You either think he’s a great guy or an asshole.”

o o o

Underestimating the lengths to which the 52-year-old Cohen will go to win a case – especially when money is no object to the client – is a mistake many a prosecuting state and U.S. attorney has made over the years. Cohen might have made a good tax lawyer; he’ll find and wring every loophole in the statutes to defend his clients.

Like the time a decade ago he enlisted Mark Ware, then a 17-year-old office clerk, to go undercover and learn the truth behind a young woman’s allegations of rape against a young Tampa attorney. “He gave me strict instructions not to coerce her in any way,” recalls Ware, who is now a public defender in Dade City. “I tried to get her to open up. It wasn’t hard. We were lying around (the beach) and she said nothing really happened. She was being forced to press charges by the prosecutor and police. She said she wanted to tell someone. I said, ‘I have a friend who knows Mr. Cohen.'”

Ware led the woman to Cohen. Charges against the attorney were dropped but the prosecutor filed a grievance against Cohen with the Florida Bar.

“I considered that creative lawyering, creative fact-finding,” says Cohen, “and I offered no apologies for it.”

Steve Rushing – now a Pinellas County Court Judge – was the investigator for the Bar on Cohen’s case. He asked Cohen why he hadn’t told the Bar he was using Ware in an undercover role.

“Because I didn’t want them to know,” said Cohen.

Rushing cleared the lawyer.

In his 1990 defense of Dr. William LaTorre, the St. Petersburg chiropractor accused of four counts of vessel homicide following a boating accident, Cohen hired University of South Florida sociologist Harvey Moore to determine whether a change of venue was appropriate due to extensive media coverage. Then he used Moore to conduct shopping mall surveys and mock juries to identify issues that would be important to the jury in evaluating the charges against the chiropractor.

The outrageousness most people remember Cohen for is the full-page ad he purchased on March 2, 1986 in the Tampa Tribune at the height of then-U.S. Attorney Bob Merkle’s campaign to indict State Attorney E.J. Salcines. The gigantic type read: “Merkle’s McCarthyism mentality is a threat to innocent people.”

“During the Robert Merkle years, Cohen was at his prime,” says reporter Kevin Kalwary, who has covered the attorney for 15 years, first at the Tribune and now at WTSP Ch. 10. “That ad certainly was a new one for the legal community. He was going to fight in the courtroom, in the office, in the streets, in the media. He was fighting for E.J. Salcines everywhere.”

Although Cohen admits to going undercover himself at times — “sitting in a barber shop, next to someone in a tavern, infiltrating their circle of friends, acting as an orderly in a hospital — I haven’t done that — asking someone, ‘How’d that happen?'” — he says there’s more to his career than blue smoke and mirrors.

“I don’t think tactics have anything to do with successes I’ve had,” says Cohen. “I like to think my commitment to my clients and my relentless preparation and my own advocacy skills are what permit me to be successful. Not the tactics people talk about. I’m a creative lawyer. And that’s an example of it.”

o o o

B.C. knows prosecutors.

He was 17 years old when fate found him sitting in a Tampa courtroom, listening to his younger sister Hope give testimony about a teacher she felt was unfairly dismissed. But it wasn’t his sister’s emotional report that riveted young Barry. It was the performance of prosecutor Paul Antinori. Barry even sent Antinori a letter: “When I get out of school, I’m going to work for you.”

Upon graduation from Mercer University Law School (Macon, Ga.) in 1966, he appeared in State Attorney Antinori’s office without an appointment, without even a resume.

“Paul said, ‘Where’s your resume?’ I said I don’t need a resume. I’m going to make a damn good trial lawyer,” says Cohen.

“He said, ‘You and I have a destiny together,'” confirms Antinori. “And I said, ‘I think you’re right.’ So I hired him.”

They left the state attorney’s office together and formed the firm Antinori, Kazin, Cohen & Thury. It wasn’t meant to last. Cohen’s thirst for criminal law was unquenchable; Antinori wearied of it. They separated. To this day, there is a tentativeness in each’s polite tone when asked to speak about the other.

Criminal work proved to be Cohen’s calling.

Over the years, the biggest, most controversial cases have come his way because of his reputation for doing whatever it takes to protect his clients’ interests.

“When somebody comes to you to represent them,” says Cohen, “they’re putting their life and freedom in your hands. It’s the biggest compliment a lawyer can receive. I take that very seriously. I take the highest probability of winning. I want the client walking out the door with me. I don’t want to look in the client’s children’s eyes and say,’I’m sorry.’ I sure as hell want my lawyer over-prepared if my freedom is on the line.”

o o o

Dr. William LaTorre met Cohen met professionally — at LaTorre’s St. Petersburg chiropractic office. “I hurt my back playing racquetball and he did a few adjustments for me,” says Cohen.

LaTorre needed Cohen’s services following an Intracoastal Waterway boating accident at Indian Rocks Beach on May 27, 1989. LaTorre’s 35-foot cigarette boat struck a craft half its size which crossed its path, killing four teenage passengers in the smaller boat. “When one of the boaters started calling (LaTorre) a murderer at the scene,” says Cohen, “his wife Wendy called me.”

Pre-trial publicity in the case rose to a deafening roar with accusations flung to and fro. Emotions were pitched against LaTorre in Pinellas County; clearly, the public believed, the chiropractor was guilty of vehicular homicide.

Once the case began, Cohen deflected media attention from his client. One witness claimed to have been conned by Cohen and a private investigator. Another begged a judge for relief from Cohen’s mercenary questioning during a deposition. And in court, Cohen dropped the biggest bombshell: at least two of the teenagers in the boat LaTorre hit had been drinking beer and smoking marijuana before the accident occurred. This put into grave question the lone survivor’s testimony about whether the accident occurred in open or restricted waters, a crucial point in the case.

A jury acquitted LaTorre in less than an hour. Triumphant, LaTorre took the jury to lunch and later to a pizza party – a flamboyance which aggravated many people who didn’t believe the verdict and gave more credit to Cohen’s flash than LaTorre’s innocence. Relentless and apparently guileless, LaTorre even went on a public relations tour managed by Hill and Knowlton which included such bizarre scenes as an appearance on local cable television to promote boating safety.

Winning the six-week LaTorre case – one of the most expensive in Pinellas history – was surely one of Cohen’s greatest victories. Behind the scenes, however, a furor was erupting over Cohen’s bill for services rendered — $1.7 million — and LaTorre, who already paid almost $1-million, filed suit.

“I’ve cashed out my life insurance policies, my pension — I’ve got nothing left but my practice,” says LaTorre. “He’s forcing me into personal bankruptcy. I exhausted every dime I ever had to prove my innocence and then my attorney says I owe him another $700,000. I said Barry, I don’t have anything else. This fee is exorbitant! You worked real hard, you won. It’s not something another lawyer couldn’t have done. But you did great.”

Cohen was surprised by LaTorre’s suit.

“The written contract between us is the best evidence of what happened,” he says. “There is no cap on the fee. It was an engagement fee of $500,000 and an hourly fee ($350 per hour in court, $275 otherwise) if it went over that. It says there’s no oral agreement outside the contract.”

Few — if any — lawyers in town will suggest that Cohen over-billed his client.

“The fee sounds like a lot of money,” acknowledges attorney Nick Matassini, “but he gave that man his career back. Had he been convicted, all that would have come to a standstill. The guy is young — he’s got another 20 years that he can thank Barry Cohen for.”

“God bless him,” says George Tragos. “God bless Cohen for getting a fee like that. If you can get it, go for it.”

LaTorre agrees that Cohen is a great lawyer but adds that his former counsel is “a horrible businessman.”

“He was a patient and a friend,” says the chiropractor. “As a man, I felt like he duped me. We shared a lot of private things in our lives. For 19 months we bonded like you wouldn’t believe. And I loved him. Now for him to force me into personal bankruptcy — C’MON! A million bucks is a lot of money in anybody’s view.”

“Bill is a businessman,” answers Cohen. “He prides himself on being a good businessman by capitalizing on my being a bad businessman. He thinks he can negotiate his fee. He didn’t care too much about my business acumen when he was in the ambulance at the scene of that tragedy. My position is, I didn’t try to negotiate his sentence. He could have done 10 years, 60 years. He’s not interested in negotiating his sentence, I’m not interested in negotiating his fee.”

(LaTorre dropped his suit in October. Within hours, Cohen counter-sued for the outstanding balance, legal fees from LaTorre’s suit, interest and penalties.)

o o o

A recent case found Cohen in the unaccustomed position of representing the victim of crime. He was retained by the 21-year-old Clearwater woman who alleges she was raped by up to five young men on April 27 at the home of Tampa Tribune President James Urbanski. (One of the alleged attackers is Urbanski’s son, Mark.)

The woman was the subject of fierce pre-trial attacks by one of the defendants, Carl Allison, and his attorney, Frank Vaccaro. Vaccaro described the alleged victim as “scurvy,” his client called her a “blatant whore” and Vaccaro announced his intention to “assassinate” the woman’s character at trial.

Her family complained to Cohen that she was being raped again, this time in public. Cohen sent a letter to Vaccaro asking him to cease and desist. “He engaged in a course of conduct I felt was bizarre,” says Cohen. “I wrote him a friendly letter, asking him to get help.”

Vaccaro instead stepped up his barrage, now including Cohen in his verbal assaults.

Cohen sent a second letter, this time more pointed. “To permit your client, whose judgement you have reason to question (to say the least), to go on public television and call my client ‘a blatant whore,’ is professionally unconscionable,” read the letter, in part.

Vaccaro responded to Cohen on Aug. 1 by sending a rambling, six-page, single-spaced, typed letter by messenger that sets forth in excruciating detail Vaccaro’s education, qualifications, hard knocks, mortgage and financial data. A postscript added even more scurrilous attacks on Cohen’s client. He wrote, “As to my verbiage of assasinating (sic) her character, that was too kind. Her character, and I know what it is, and you know what it is, and you know what I know about her, and I know what you know about her and you know what the government knows about her, ha!”

Vaccaro also included several copies of Cohen’s second letter and 13 differently defaced versions plus copies of Vaccaro’s degrees and honors, marked-up pages from “Torts Cases and Materials,” Webster’s New World Thesaurus and the Florida Statutes on defamation and libel with messages to Cohen such as, “Boy you are really stupid!” and “Barry Be careful-smart guy!!-Me!”

Cohen told police that Vaccaro threatened “to do me Sicilian-style,” a not-too-subtle suggestion of potential physical harm. Cohen carried a gun for protection and asked a friend to stay at his Redington Beach condo with his wife and stepdaughter for their safety whenever he was away. Five days later, as a result of Cohen’s complaint, sheriff’s deputies took Vaccaro into protective custody against his will for psychiatric evaluation.

“For some reason,” says Vaccaro, “(Cohen) perceived a threat. But I didn’t threaten him. I wouldn’t do that. I in no shape or form threatened him.”

On his release three days later, Vaccaro resigned as counsel to rape case defendant Allison.

“I don’t think my zealous representation has hurt (Allison’s) case,” says Vaccaro. “I would submit it has helped it. Until I began, these boys were punching bags in the press. We took a zealous defense. I think that probably assisted him.”

The rape trial is tentatively scheduled for February. Cohen — who plans to launch a civil suit against the five young men implicated in the rape — admits he was sorry to see Vaccaro step aside.

“He generated a lot of bad feelings toward his client. There was enough bad publicity that (Vaccaro’s client) passed LSD to my client and shoved a bottle and (other objects) up her vagina when she was passed out. My intuition is he did his client a tremendous disservice. I would probably have preferred him in the case. He was burying his client,” according to Cohen.

o o o

Tampa welcomed the Cohens — including Barry’s younger sisters Cynthia and Hope — in 1941. They lived on Watrous Avenue, a far cry from the polish and splendor in which Cohen would later raise his own family in Culbreath Isles.

As their only son grew up, Irving and Rhea Cohen were by Barry’s side everyday, working side by side in a series of family businesses. When it was the car wash and 12-stool restaurant, dad was the cook, mom the waitress and Barry the dishwasher. Later, they opened Hope Salvage together.

Irving was gushingly proud of his son, and he could often be found sitting in the courtroom when his son handled big cases.

“I was always very proud to have him there. It was the greatest feeling in the world to make him proud. When my dad died in 1975, I lost my best friend,” says Cohen. “For years, I was at his grave every week.”

That closeness is a relationship Cohen maintains with the three children he and ex-wife Marcia have — twins Kevin (a senior at Mercer Law School) and Steven (studying for a Ph.D in psychology at Pepperdine), 26, and first-born Geena, 28 — even though the family was run like a branch of the judiciary.

“We had trials, family meetings where you could say whatever you wanted,” recalls Geena. “Dad was the judge. If the issue was who did something, we’d be granted immunity. And instead of being grounded, we’d have to write essays: ‘Why I Love My Brother.’ ‘Respect.’ ‘What My Brother means to Me.'”

As recent history demonstrates, even when Cohen tries to leave his work at the office, it sometimes threatens to follow him home.

“One time, a guy escaped from jail and he came to our house. He had dinner with us and then my dad took him back,” says Geena. “When dad was a prosecutor, a guy he put in jail threatened him and escaped. The family hid out at the beach for a few days ’til he was caught.”

If one of the children called him at work, secretaries were instructed to interrupt no matter what and put them through. One year, Cohen had to make an early exit from a father-daughter dance, disappointing Geena. He swore next year would be different. But sure enough, a judge insisted Cohen be in his Ft. Lauderdale courtroom the night of the dance.

“Counselor,” said the judge, “I don’t set my calendar around school dances.”

“Your honor,” said Cohen, “I don’t mean to be disrespectful, but I won’t be trying a case in your court that day. I’ll either be at the dance with my daughter or I’ll be in your jail.”

Marcia often brought the children to court to see their father work. The Tampa Tribune once printed a picture of each of the boys struggling to carry dad’s briefcases on the way out of one of Arden Merckle’s many trials.

During important trials, Cohen would sometimes get home long after the twins went to sleep. He’d tip-toe into their room, kiss them goodnight and inevitably, Kevin would wake up and ask, “Did you win yet?”

Cohen and Marcia divorced in the mid-1980s after more than 25 years of marriage. They are still fairly close; Marcia continues to maintain and update her ex-husband’s scrapbooks, for instance, as she has since he began his career in the state attorney’s office.

The second Mrs. Cohen, Terryn, 35, married Barry in September 1990. She was his office manager at the time; today she’s a full-time student at Stetson University College of Law, pondering whether or not to follow her husband into criminal practice. This is the second marriage for both; Terryn has a 7-year-old daughter.

Terryn knows she is married to a Type-A workaholic. He’s the one she calls “Mr. Cohen,” a throwback to their employer/employee relationship.

“Every now and then I say, ‘Mr. Cohen, if you see Barry, will you tell him I miss him?’ That’s rare, but when it happens, it means I’m lonely,” she says.

“Last week,” confirms Barry, “I was in a meeting and she called me and said, ‘If you see Barry, tell him to call me.'”

“There ARE two personalities,” says Terryn. “I can see the change come over him in the morning. In one minute he’s my husband, talking about home and family. Then a cloud comes over him and he’s at work. He’s ‘Mr. Cohen.’ Or we’ll be at dinner and I’ll say, ‘Where did you go? Come back!'”

o o o

Down the road, Barry Cohen sees himself continuing to do the white collar criminal defense work upon which his success and fame is based. But he also seeks to evolve his business into a 60/40 mix with civil litigation, which requires a different kind of pressure.

“The criminal practice — the stress of it catches up with you after a while. You really need a diversion,” he admits. “A lot of people, when they have a real serious civil problem, they want someone who they perceive as being aggressive and not intimidated.”

One possible direction is political, although Cohen — a card-carrying Democrat — won’t be pinned down as to whether he’s interested in elective or appointed office or the politics of power brokering.

“I’m getting real concerned with the way we’re going as a society,” he says. “I’m feeling a little selfish having not done anything to improve it. I may start doing more to fix things. Sometimes I think if I was independently wealthy, I’d run for governor or U.S. Senate. But I’m not and I don’t plan to.”

He’s also intrigued by the potential of welcoming daughter Geena into his firm as a partner one day. “She wants to try some cases with me; we’re looking for the right one,” he says. “We’re too alike to work in the same office together — we think — so we want to try it on and see how it fits. I have my own style of preparation; she has hers. We’re going to see how the two match.”

Geena, who is in her fourth year of practice, is no hurry to rush home to Tampa.

“Everywhere I go, I’m ‘Barry Cohen’s daughter,'” she says, awash with pride and a need to stand alone. “Right now, dad and I are both headstrong and have a real good relationship we don’t want to jeopardize. A lot of things need to settle before I make my decision.”

If such a partnership does come to be, Geena has a name picked out:

Cohen & Father.

“He laughs,” she says. “But he doesn’t like it.”

SIDEBAR:

The Fine Print

RESEARCHING the past clients of Barry Cohen produces a rogue’s gallery of the bay area’s most colorful defendants:

— Henry Hill. A hired hand in the beating of Tampa lounge owner Gaspar Ciaccio over gambling debts in 1970, Hill rose to national prominence in Nicholas Pileggi’s book WISEGUYS and the 1990 movie, GOODFELLAS.

— Arden Mays Merckle. The former Hillsborough County chief justice stood accused of violating the civil rights of Boca Raton real estate broker and former football star Jack Harper. Cohen represented him in four major related cases over nearly a decade.

— Floyd Price. Price was accused of the strangulation murder of 20-year-old Deborah Jean McCartney after she was found in a Kissimmee drainage ditch. The case was re-told in CONFIDENTIAL DETECTIVE magazine.

— Jerry Bowmer. A Hillsborough County Commissioner involved in one of the region’s most celebrated influence selling scandals.

— Ira Amazon. Amazon was accused of stabbing to death his next-door neighbor and her 11-year-old daughter in 1982. Conviction was a foregone conclusion due to Amazon’s confession; Cohen kept his client off death row by pleading successfully with the jury for life in prison.

— E.J. Salcines. The long-time Hillsborough County state attorney was the subject of a three-year witch hunt led by then-U.S. Attorney Bob Merkle from 1984-86. But a federal grand jury failed to hand down any indictments in its investigation of alleged public corruption.

— Elvin Martinez. The state representative was charged with tax evasion.

— Gary Sheffield. The Milwaukee Brewers third baseman — and nephew of New York Mets pitching ace Dwight Gooden — retained Cohen as counsel after his second run-in with Tampa police officers in 1990.

end