Profile By Bob Andelman

(Originally published in Tampa Bay Life, 1990)

“This is like the guy next door that you grew up with,” says Russ Albums. “If you wanted to have a best friend, this would be the guy. He’s a prince.”

It’s one of those nights.

Saturday night at Tampa’s Rock-It Club and a few hundred people are crowded together, ready to party. Pretty young women in skin-tight half shirts, mini-skirts and teased hair. Rugged young men in tight jeans, leather boots and air guitars strapped over their shoulders.

One man has brought them all together.

Unfortunately, he’s got about a million other places he’d rather be right now.

It’s not the club, the audience, the pay or anything else but him. Bobby Friss plays rock ‘n’ roll 300 nights a year — tonight he wishes it was only 299 nights.

But standing outside in the cool air after his first low-key set, Friss is mentally preparing to give his best when he goes back in, whether his heart is in it or not. That’s just the kind of guy he is.

“It’s one of those nights,” he says with a shrug, that silly grin coming up from under several pounds of blond hair. “You play the same thing so many times. I have played 300 nights a year for 15 years. So playing a Saturday night in Tampa is not an ‘I can’t wait to do it.’ ‘Cause I do it every night.

“My days for 15 years have been, get up, take care of business, take a shower and come to work and play music. Just ’cause people get revved up and say, ‘I’m going to see Bobby Friss!’ — it’s just another rock ‘n’ roll night to me.”

The grin becomes a frown. Friss — by all accounts the most professional, workman-like musician in the state of Florida — knows what he’s said is the truth but it’s also a mood. It will pass — in fact it already has. “I’m going to have to turn myself up a gear,” he says to no one in particular. “A night like tonight, to be honest, I need a kick in the ass. I came in here tonight apathetic.”

Trouble is, an average night in Tampa before his hometown fans pales after the experiences of the last few weeks. Overfl ow Spring Break crowds in Daytona Beach and Panama City. Opening gigs for Otis Day & the Nights and comedian Jerry Seinfeld. Over 40,000 people in Pensacola. “Then I come to the Rock-It Club on a Saturday night and it’s a little anti-climactic,” he says. ” People don’t understand. They work days at a computer, they slow down, take a break. I can’t do that. I’m on stage. I control the crowd. If I’m crazy, they’re crazy. If I do nothing, they sit there like flounder. I want them to have fun.”The Act

“You have to do more. Nobody is blown away by virtuousity. They work all day, they want to be entertained at night. They don’t want to see guys getting off playing guitar.”

“You have to literally reach out and strangle the audience. There’s just too many distractions. I’d love to be Bruce Springsteen, singing just my songs. But you’re the sideline at the club, you’re not the main act. That’s why I’ve become the guy who jumps on the table, slugs down a beer. Whatever it takes. I can’t stand having a room full of p eople milling around, not watching what I’m doing. The only thing worse than playing to an empty house is playing to a packed house that’s not watching. Whatever it takes, I’ll do.

“Once, a guy at a club had inversion boots. I hung from scaffolding 30 feet above the stage playing my guitar. I’ve gone across streets and stopped cars and played on their roofs while the band is playing indoors. I invited the whole audience on stage one night at the 49th Street Mining Co.

“I randomly select somebody every night and slide a Miller Genuine Draft down my guitar neck into their waiting hand. I do it every night. It’s predictable, but everybody gets up to see it. It’s like Sammy Davis Jr. doing ‘Candyman.’

ART HAEDIKE, owner, Porthole Lounge, Tampa: “He’s played his guitar in the parking lot. Once, he was singing in the john with the microphone and you’d hear the toilet flush.”

RUSS ALBUMS, WYNF (95 FM) disc jockey: “”He’ll sit down and schmooze with the audience and let them play his guitar while he has a beer.”

RICK RICHEY, childhood friend: “I rember walking through the parking lot of Mr. T’s Club 19 in Clearwater and he was standing there with his cordless guitar, wailing away. I was trying to figure out what was going on.”

“It’s a ‘slap’ society. People want something to slap them in the face. You get overlooked if you’re subtle.”

“We play about four or five originals a set and I better do some damn good cover material in between because these people are too primed to hear it.

“It’s too bad. We should be able to just play our own music. But I think even Led Zeppelin — unknown — would have a problem doing three sets of original material.

“The bands in Tampa Bay playing one or two nights a week — I guarantee they’re doing day jobs and starving.

“I run a business. The band is on salary. As soon as I decide we’re only playing originals, only playing concert-type shows, I take away the tightness of the band. In order to sustain their lifestyles, the guys would have to get day jobs. That’s what breaks up bands. Some weeks you don’t work, you work one night. The music becomes a sidelight. Right now, this is what we do. No distractions. During the day, we write, we record. We work on furthering our careers.

“Stranger and myself gross the most money among bands in town. That’s not to say there aren’t a town of other bands that aren’t as good as we are or better. The thing is, we’re the ones playing cover songs on Tuesdays and Wednesday nights. These other bands don’t want to do it. That’s great, but they’re not going to have the big money, they’re going to have to get a second job.

ART HAEDIKE, Owner, Porthole Lounge, Tampa: “When they say Bobby Friss cleans up at the Porthole, they’re right: we have him sweep up and he washes my car.

“He’s a good, consistent act. One of the best, if not the best, rock ‘n’ roll entertainers in Tampa Bay. Bobby works the crowd. A quick wit, lots of extraneous stuff. He gets more money than most of the other bands that play here. Maybe they haven’t rubbe d elbows with the right people yet. But they’re probably the best club act working. The nights are a little better when he’s around.”The Studio

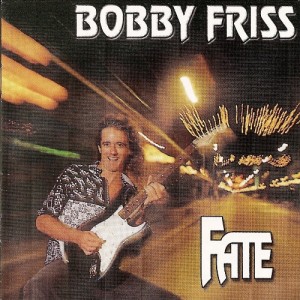

Returning to the studio early in 1990 to record his second album, Friss took a long hard look at his first effort and decided it wasn’t the best he could be. There were only a few songs — “Long Way Down” and “Can’t Come Back,” which has become a local radio staple — that he is fully satisfied with two years later. It is driving him to do be more critical this time around.

“I learned a lot,” he says. “There’s good parts, but I don’t think, overall, the songs hold up.”

There are two roadblocks for Friss on his new record. First, because of his budget limitations, he must once again produce the album himself. Despite the engineering expertise of Morrisound Chief Engineer Jim Morris, that can be a drawback in the experien ce department. “I know what sound I want,” says Friss. “But I don’t necessarily know how to get the sound.”

Another problem is time. Being on the road five days out of every six cuts into available recording hours. That’s why the first album was done over four months instead of four weeks. “I just go in and do it when I can,’ says the guitarist. “It’d be nice to go in and do a month straight but I can’t afford the time.” When he’s on the road, Friss reviews tapes, making notes and plans for alterations.

Friss will rarely sample a new song in a club before it’s been recordedIt’s His Band

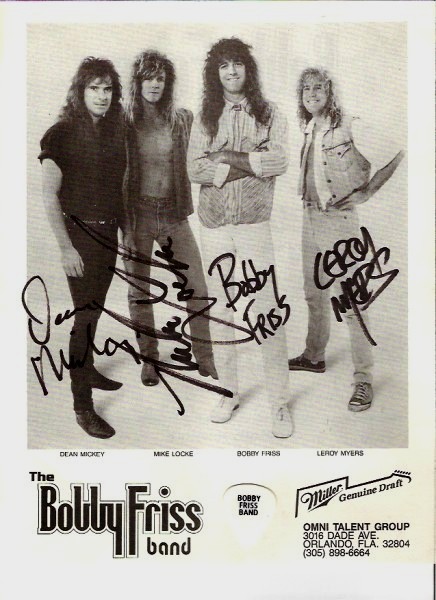

Note the name of the group: The Bobby Friss Band.

When he first formed a quartet in 1983, one thing was established from the beginning: “It was going to be my band,” says Friss. “I make the decisions, the song selections.”

Friss likes to be in control. He follows and believes strongly in his own muse, to the point of writing and composing almost all of his band’s original material. “We haven’t collaborated that much because if we get a record deal, I’d like to get it with my material,” he admits. “Not so much for my ego, but I’d like to show I have that capability.”

“My career is directed. I know what I’m doing.

Family Ties

Friss’s older brother Jay — a.k.a. “Ray Blade” — is the drummer in the Johnny G. Lyon Band.

His younger sister, Susie, is a schoolteacher.

His father Dick — “the oldest rock ‘n’ roller in the universe,” according to Friss — is the night auditor at the Paradise Lakes nudist resort in Land ‘o Lakes. He is also the older gentleman at every Friss Band show wearing a black satin “Bobby Friss Band” jacket.

“They say you must be proud,” says Papa Friss. “But if your kid is in sports or music, you go see them play. If you’ve got a kid who sells socks at Maas Brothers, you don’t go see him work. I’ve got a daughter who teaches school but I’ve never seen her teach. But why should I sit home and stare at a TV when Bob’s in town? I t’s entertaining.”

Dick and Bobby’s mom, Jackie — who lives in Rochester, N.Y. — were divorced in 1973.

Michele Wyatt, Friss’s new bride, met the musician in Michigan when he was managed by her brother Warren. Warren was reportedly not too happy with the arrangement at first. The Wyatts have a third sibling, Brett, who is quite close to Friss. Growing Up

Music wasn’t Bobby Friss’s first love. That would be sports — particularly basketball.

“Bobby’s an obsessive kind of guy,” says his dad, Dick Friss. “He was not a natural athlete, not gifted. But he forced himself. He shot baskets until after dark. He’d shoot and shoot and he made varsity at Largo High. He was never going to be a built-in basketball player, but he forced himself to get better by persistence. The same thing with the guitar. Nobody said, ‘We want you to take up the guitar.’ He went into room his with a Sears Roebuck guitar and just practiced.”

Dick says his youngest son was not the kind of boy to announce his intentions to the family — he’d just go out and do things. Like the day he took up pole-vaulting. “I said you’re a what? A pole-vaulter? He said running around a track eight times wasn’t a s much fun.” Or when the Largo Sentinel hired him to write about sports at his high school and the family found out about it by accident — seeing his byline in the newspaper. Friss was paid by the inch, so he wrote about everything from badminton to tiddylwinks, including describing his own play in basketball games — “Friss scored 10 points” — in the third person. “That’s just the way he’s always been,” says Dick, laughing.

“I was really into sports as a kid,” says Friss. “I didn’t pick up the guitar until I was 17. I missed the Beatles and Motown — I had to go back to them because I was out shooting baskets.”

Rick Richey has known Friss since they were in 7th grade together. He remembers when his pal would take his guitar out to Indian Rocks Beach every summer night and sit on the seawall, playing for the passing crowd. And Richey was road manager for the first Friss band, U.S. Steel, which played its one and only job at an apartment complex dance.

Not that Largo teen life was all dribble and strum.

“My senior year in high school I was not in the crowd I needed to be in,” says Friss. “”Let’s just say I was experienced with everything. It wasn’t a healthy environment. I was probably hanging out with people who are doing the same things now they were then.”

“By his own smarts, he rejected the things many people find it hard to reject,” says Dick.

After graduating from Largo, Friss packed a pillowcase full of clothes, grabbed his guitar and hitched rides north to Michigan. He moved in with family and eventually enrolled in journalism at Central Michigan University. If he didn’t apply his basketball intensity to studying, he at least invested his time well in practicing the guitar.

“I didn’t know anybody and the winter cold was ungodly,” says Friss. “I stayed inside and played and played. That was the year that secured my love for music — there wasn’t anything else to do.”

Higher education lasted less than two years, but Friss went on to a higher calling. He formed his first band, Force, and toured with it for six years from Michigan to Florida. He left the group in ’81 and spent six months seeking work as a songwriter in New York before relocating to Orlando. The Bobby Friss Band was formed there in 1983, although all the faces save Friss’s have changed through the years.

As Real As It Gets

In 1981, the Rolling Stones were the first rock ‘n’ roll band to have corporate sponsor — Jovan. Since then, it’s hard to find any act on the road that isn’t shilling for some product or service. Paul McCartney does it for credit cards; Tina Turner does it for cars. So it wasn’t too surprising that when Miller Beer was looking to make a long-term promotional investment in its Genuine Draft brand years ago, it searched the country for young musicians with bright futures who needed a leg up. For 10 years now, the brewery has provided promotions and music equipment for bands such as the Fabulous Thunderbirds, Del Fuegos, the Rainmakers and, since 1987, the Bobby Friss Band.

“It’s a validation of his talents that Miller would pick him up,” says Bill Templeton, editor of Players magazine in St. Petersburg. “He’s paid his dues here, always ranked as one of the top bands in town. When people see him, they know they’re going to get the goods.”

“You play for eight or ten years without corporate sponsors and you know the daily grind of paying $4 for a guitar string,” says Friss. “Then they come in and say we’re going to give you strings, instruments, guitars, posters — all these things that otherwise come out of my pocket. They step in and become big brother. There’s no cash exchanged — just equipment and promotion.”

The promotional boost is probably the best part. Each year, all 26 bands in the Miller Network attend a seminar on upcoming promotions, expectations, and public relations. They are skillfully taught how to talk to disc jockeys, reporters, club owners and fans. Then the Miller machine guides them from city to city with local advertising, parties, in-club posters, glossy pictures suitable for autographs and plenty of media contact. Friss has also recorded nationally broadcast radio commercials in which he sings the brew’s jingle and is I.D.’ed as “Florida’s Bobby Friss Band” at the end.

Miller has been a dream come true for Friss’s agent, Omni Talent vice president Rick Young. “He’s very easy to book,” according to Young. “He’s popular in nearly every city in Florida. Miller’s been very helpful with that.

“I go to Louisville, Kentucky to do a one-nighter and the PR people at Miller have already set up interviews with two radio stations,” marvels Friss. “They usually play a song or two off our record. Here I am, unsigned to a record company, getting airplay on a major station.

“Advertising money talks,” he adds, referring to the power of the beer company’s enormous marketing budget and its potential to pull dollars from uncooperative media.

Is there a downside for Friss?

“If there is,” he says, “I haven’t seen it. At no point in the night do I hold up a beer and say, ‘Let’s have Miller Geunine Draft.’ That’s not what they want you to do. They want to be associated with you. (The audience) will figure if you’re affiliated with it, it must be good. And if it wasn’t a good beer, I wouldn’t drink it.” (Trivia: While in Michigan, Friss was a Stroh’s drinker; prior to the Miller deal, he preferred Budweiser in Florida.)

What does Miller get out of the connection?

“We feel the Bobby Friss Band has a lot of potential,” says spokesperson Mary Houlihan. “We want to help Bobby as much as we can. We think he’s going places. Miller wants to take the burden off promoting their tours. If they’re going to do six weeks of one-nighters, it takes their concentration off the music. We want them to do what they do best — perform their music.

“Miller is looking for a positive lifestyle association with these bands. They’re looking for people to go out, have a good time listening to the bands and the want Miller Genuine Draft to be a part of that. We don’t want them to be salesmen for the beer. One mention would be nice.”

“They’re trying to promote their Miller Genuine Draft Beer,” says Friss. “They’re looking for men 18 to 35.”

Participating bands don’t have to do much once they’re chosen for the Miller program. They place a banner behind them that reads “Miller Presents … ” They are introduced on stage the same way. They are not asked or even encouraged to shill for beer, although if they drink on stage or in a club, the company prefers they be seen with Miller products.The Studio

Drums make a variety of noises depending on how, where and how hard they are hit. Cymbals are even trickier.

Friss is behind the sound board in Morrisound Studios’ main recording studio, listening to drummer Leroy Myers bash the skins and cymbals. Neither is happy with the “crash” coming off the cymbals so they load up in Friss’s band and head for Thoroughbred Music on Hillsborough Avenue. This rock ‘n’ roll supermarket is to musicians what Home Depot is to handymen and Workplace is to small business people: Mecca. The Friss party immediately gets sidetracked by amps, the guitar museum, friends and fellow players.

“It’s a sweetheart isn’t it?” says Friss, caressing a ’62 vintage Stratocaster guitar. “It’s like Christmas everyday here.”

Morris, checking out amplifiers, says working with Friss in the studio is a unique experiencing. “He knows exactly what he wants,” says the engineer. “He’s one of the few self-produced artists who knows what he wants. He makes my job easier. He’s businesslike, efficient. It’s not a party. We get down to work and get results. He’s a very directed guy. I imagine he’s that way about the rest of his life. Planned out, doesn’t leave a lot to chance.”

Eventually, the group catches up with Myers in the drum department and Friss narrates the play-by-play.

“We’re in the drum department,” he begins. “This is the least interesting part of the place. It’s guys who beat on plastic and metal for a living. They pretend it’s music, but we know it’s just noise. Drummer are just diddlers … ”

Myers takes three cymbals at a time into a sound-proof room and Friss, Morris, Brett Wyatt and I make the mistake of following him in. Stick in hand, Myers bangs on each one numb to the Crash! in the rest of our ears.

“They all sound the same to me,” says Friss.

“They’re all different!” protests Myers as Friss laughs.

Myers has lasted longer than any other player in the Friss band — six years. They met as rivals in a Michigan “Battle of the Bands” competition in ’79. Years later, Myers was vacationing in Florida when Friss called. Now, when the band hits the road, Friss and Myers are roommates. (Myers likes his hotel rooms freezing, Friss prefers moderate.)The Next Day

Returning to Morrisound for the last time before the band hits the road for most of April, Friss is concerned about a ballad he has recorded, “Lonely One.”

“It’s still got some holes in it,” he complains to Jim Morris. “It’s hard to believe we have as much as we do in there — it’s still empty.

“It’s good to have some holes,” rebuffs Morris. One recurrent critical blast against Friss is his habit of putting to much sound on his recordings. He’s not from the less is more school of thought.

The Kids

Christmas, 1985.

Rock radio station WYNF and the old Mr. T’s Club 19 sponsor a benefit concert for the Children’s Home of Tampa — a residential treatment center for abused and neglected kids — featuring local bands and master of ceremonies Bobby Friss. They raised $5,000.

For Friss, it was a major turning point: the star turn helps break him out of the pack of club bands and begins his association with the Children’s Home. The connection has grown from playing and organizing the annual holiday show to regular trips to the non-profit’s villas, where Friss plays his guitar, shoots baskets and presents youngsters with a positive role-model. It has also put him in a position to rub elbows with the Children’s Home’s better-known benefactors, including the Bullards and Steinbrenners.

Friss donated proceeds from the song “Suzie Darling” off his first album to the Home. And he’s hoping to organize a “Christmas in July” concert to benefit the Home this summer.

“I did it at first because it made me feel good, giving something back. At Christmas, it’s nice to think about other people,” says Friss. “Now it’s just part of me. It’s not, oh, I gotta do my Christmas thing. I go out there all the time. I break the stereotype of what a guy with long hair who plays in a band can be. They don’t need me to tell kids right and wrong. They like me to come out and be a friend. I like to go because the kids are cool.”

“The kids love him,” says Michele Pernula, public relations coordinator for the Children’s Home. “Your initial thought of a rock ‘n’ roller is not Bobby Friss, other than the long hair. He’s just been a wonderful person, a great role-model for the kids, too. He tells them to keep hanging in there, work hard, and you’ll do well.

Year-’round involvement is important to Friss, because it helps dispel the notion he’s involved just because it makes good P.R. For instance, while he has a basketball court in his own backyard, he prefers to play at the Home.

“I use it all the time,” he says. Then, laughing, “I helped buy it.”

Birdies and Bogeys

When he’s in town and not recording, Friss hits the links with WYNF (95 FM) air personality Russ Albums and Greg Billings of Stranger.

“He’s got that rock ‘n’ roll swing,” says Albums. “It’s a pure powerfade with a grunt like you heard when (boxer) John Mugabi gives you a punch in the solar plexus, a rush of wind like Hurricane Elena through your ears. Then we go looking for the ball.”

On a good day, Friss says he’ll shoot a 90, but 100 is more likely. “I just haven’t turned the corner,” he says. “I’ll shoot a couple good holes, then I fall apart.”

They play “wherever they want to comp us,” says Friss. “We’re fortunate. We have a lot of golf courses that like my music and Russ’s show.”

Golf has been good on the road as a soft public relations tool.

“Most DJs seem to play,” says Friss. “A lot of club owners play. It’s good to get to know people on a more personal level.”Mr. Business

There are three bottles of Miller Genuine Draft beer in the Friss refrigerator and one well-aged bottle of Seagram’s Wild Berry wine cooler. Bobby Friss may have his drinking tricks on stage, but at home, he’s stone cold sober.

“He’s almost a poster boy for the ‘Say No’ syndrome,” according to his father. “He uses (alcohol) in his act, but not in his personal life. You can’t be as busy as he is and be in a fog all time.”

That must be a significant difference between Friss and other local band leaders because virtually everyone interviewed about the musician commented on the sober focus he keeps on business matters.

“He’s been the most business-oriented musician for both the band and the club,” according to Art Haedike of the Porthole. “It’s always been, ‘What do we need so we can both make money?'”

Friss — whose band can draw anywhere from $500 to $4,000 for a night’s work — takes his role as benevolent dictator (his brother Jay jokingly refers to the position as “D.H.” — “Designated Hitler”) seriously. He is responsible for a six-man, full-time payroll — paid weekly in cash, incidentally, because that’s the way the band likes it. The four musicians and two roadies working for him rely entirely on the popularity and market value of the name Bobby Friss.

In the early days, Friss followed a simple philosophy: “In tune, on time, with clean hair.”

And forget about hoping to die before he gets old. This is a home-owning man getting married this June 17 with plans to have children and a future.

“Being 34 — if somebody else started working with a firm at 21, they’ve got 14 years of pennies put away by now. I don’t,” he says. “I’ve got to be prepared for that. But a guy in my position is always thinking you’re going to make that big jump, that you’re going to have so much money, which keeps you going, I guess.”

Leroy Myers says his boss is shrewd.

“We get more airplay than we probably deserve around here,” says the drummer. “That comes down to the fact that Bob, on a daily basis, deals well with people. I’m sure the disc jockeys and club owners see him differently than guys in younger bands who come in and say, ‘Hey, dude,’ and ‘Mind if I smoke a joint?’ They see him as an equal, a guy running his own business.”Yesterday, Today, & Tomorrow

“He just needs that one break to make it to the big time,” says friend Rick Richey. “There’s no one more deserving than Bob.”

“In the nine years I’ve known him, he’s really changed a lot. If you really want to be successful at something like music you have top be single-minded and directed. But he has a good balancer and hasn’t lost that direction. He’s always looking the step ahead. He might be happy where he is,” but he’s not satisfied,” says Michele. “He’s never content to pat himself on the back and say, yeah, I’m doing okay. I think that’s why he’s making progress. And he’s very talented.”

“I like my house. I like being with Michele. This number one in my life. My number two life is being on the road,” says Friss. “But if I get a record deal and it means six months on the road opening concerts for Whitesnake, you can bet your ass I’m going to do it! When you get your shot, you have to take it.”Back to Work

Break over. Back to the stage of the Rock-it Club.

Steeling himself, doubts are dispelled and the party animal is back. As Friss makes his way back to the stage, he autographs pictures for his fans, shakes a lot of hands and says hello to a lot of people whose faces he can instantly attach to a name.

As the red LED crawl for “Ruben’s Bail Bonds” — “Traffic-Criminal-Narcotics … 24-Hour Service … 3 Generations of Successful Bail Bondsmen” — goes across the ceiling of the dance floor, Friss comes clean with the audience.

“I’ve got to admit when I came to the club, I could’ve cared less. Then I started to think about how lucky I am. I’ve got a great band, we’ve got a new album, I’m healthy, I live in the greatest country in the world — what do I have to be pissed about? I feel a little like Jimmy Stewart. I’m the happiest, luckiest man alive! This is the greatest night of my life!”

And he means it.

FRISS BITS

Home: North Tampa

Age: 34

School: Largo High

Love Life: Married girlfriend of nine years, painter Michele Wyatt, on June 17

Guitar: Fender

Professional Secret: Is a Bucanneer season ticket holder; schedules concerts around football games

Personal Flaw: “He doesn’t have a lot of patience with hammers or screwdrivers,” according to Michele.

Conversational Tip: “When I get with my close friends we don’t talk about my last gig. We talk about their kids or Michele’s art classes.”

Listen For: Many Friss songs contain Tampa Bay references. On his new album, the song “Welcome Home” mentions Lowry Park and playing pool at Mr. Stubby’s in Clearwater

Kicking Through the Ashes: My Life As A Stand-up in the 1980s Comedy Boom by Ritch Shydner. Order your copy today by clicking on the book cover above!

The Party Authority in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware and Maryland!

The Party Authority in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware and Maryland!