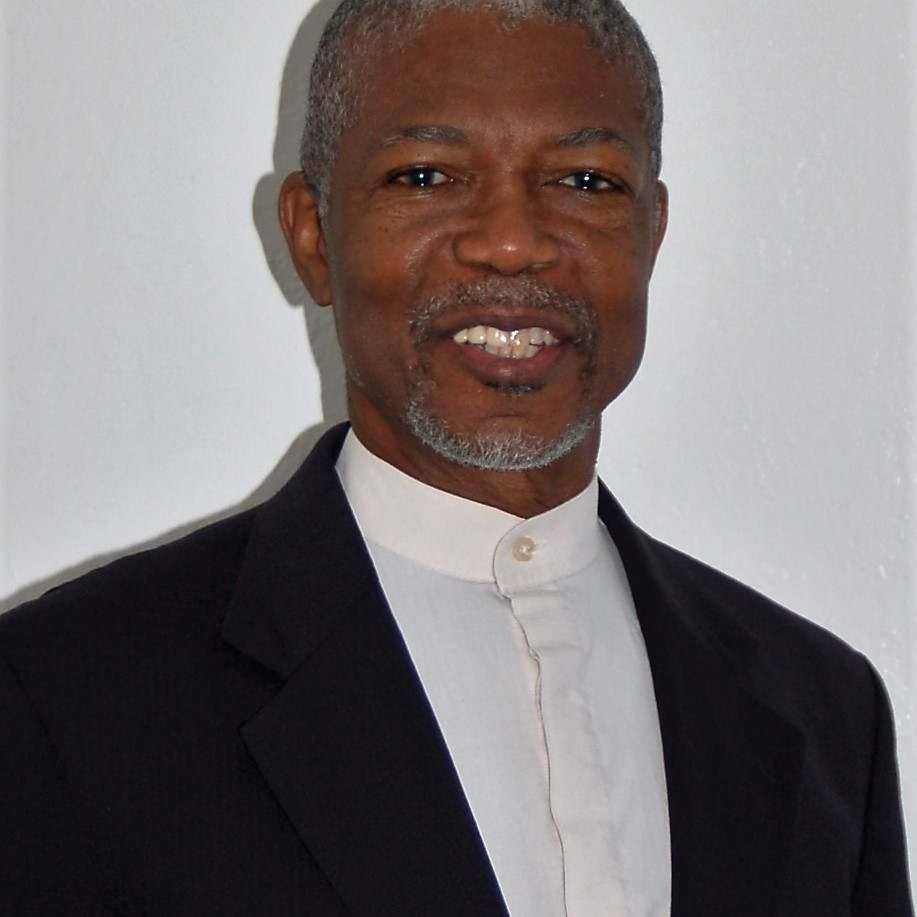

Imam Askia Muhammad Aquil as he is today (2016)

By Bob Andelman

Originally published in Tampa Bay Monthly, May 1987

It was a Sunday afternoon in late 1973, near what was then the African People’s Market on Central Avenue in Tampa.

“Somebody got shot in a bar or something, and there was some degree of disturbance,” says Askia Muhammad Aquil as he remembers the day.

Aquil was known as Otha Favors in those days. This particular Sunday, Favors would fear for his life.

“Because we (the Black Students for Peace and Power) were labeled as a militant organization, (the police were) watching us. Around dusk, I walked out of the door of my business on Central. A police car was there. They searched me. I had done nothing.

“I had a copy of Dick Gregory’s (book) No More Lies in my pocket. The officer threw it on the ground, put me in the back seat of the car. They rode me around for an hour or two. By then it was dark. The officers were really hostile. I’d been reading about things in other cities where people were found by the sides of the roads. After an hour of being parked in the back of the police station, they said all right, you can go.”

No harm came to Favors that day. His arrest was just one episode in a series of threats, harassment and intimidation by local police under the heading of “field interrogation” that African-Americans had to endure just a decade ago.

Relations between law enforcement authorities and the man who became Askia Muhammad Aquil in 1976 have improved drastically.

The converted Muslim is now perceived in a different light.

Instead of wearily fighting the establishment, he, like many activists of yore, has become a 20th-century turncoat. He has joined the enemy.

“I guess it is a turnabout from when he was known as Otha Favors,” remarks Bobby Bowden, manager of community affairs for the City of Tampa. Bowden got to know Aquil when Mayor Bob Martinez appointed Aquil to serve as co-chairman of the Community Awareness Task Force last year.

“He has a genuine concern for this community,” according to Bowden. “He has thought it better to work within than outside.”

“He has a very good relationship with the chief of police and the sheriff. He’s a well-rounded individual and I think he put all of his energies in a positive fashion to see things shape up in the inner city.”

WHAT MAKES A militant?

Otha Favors was a student at Gibbs High School in St. Petersburg, involved in church and neighborhood activities. He once considered a journalism career and spent a summer as a St. Petersburg Times intern, His life, by all standards, was simple and carefree.

The day Martin Luther King was murdered in 1968, a tremor went through young Favors.

“I was confronted with my own need to be involved and accept some social responsibility.” Favors took up the banner of black power and black nationalist issues while getting his associate’s degree at St. Petersburg Junior College.

Transferring to the University of South Florida in Tampa, Favors saw an ad in the Black Panthers’ newspaper offering a guide for establishing black studies programs on college campuses. Favors ordered it and worked with other students to apply it to USF.

On the day they decided to present the curriculm to the president of the university, the students walked toward his office. As Favors put it. “He saw us coming and locked the door,” thinking trouble was brewing. The group had to slide the proposal (which became the current Afro-American studies department) under the door.

“That’s how I got the label ‘militant,” Aquil says, noting a Tampa Tribune headline referring to him that way. “I hadn’t burned any buildings, shot anybody. We said the education we got was lacking.”

“Quite a few of the people that were involved in the ’60s are still around doing different things. Very few are active on the same level as 18, 20 years ago. Alot of ’em got stirred up over Vietnam. After it was over, they went home. There were still civil rights, education and employment problems that were not addressed.

“In my opinion, there is going to be a resurgence of activism, even though it’s different issues and different people. I don’t think the activities will be of the same high intensity, seemingly threatening, explosive incidents we had (in the ’60s),” said Aquil. now 38. “There are some issues we need to march and protest, but there are more constructive ways.

“Part of what we were trying to assert in the ’60s was that (First Amendment) right. We African-Americans were denied the right to free speech. That degree of progress has been made. People can speak freely and protest without being afraid of being attacked by dogs,” he says.

Aquil lists political, economic, educational and cultural gains as priorities for the African-American community agenda in the ’80s. ·

“We cannot attempt to function in the ’80s the way we did in the ’60s. If we do, in the year 2000 we’ll find ourselves with the same problems.”

Increased employment of teenagers is high on Aquil’s list of social cures.

“So much of the crime (and) drugs being done by teenagers are economically motivated. The business community is largely ignoring what is a very large problem. These teenagers are unemployed, day after day, week after week, not having the opportunity to do an honest day’s work, get a paycheck and buy some of the things that other people do.”

One of the few regrets Askia Muhammad Aquil has in his life is that he never finished his bachelor’s degree. He now works as an advertising salesman. When he was younger and had the time and money, something more important came up.

“I could have money in the bank and still be a second-class citizen,” he says. “A slave’s first responsibility is to fight for his freedom. The other things, you fight for as you go along.”

The Party Authority in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware and Maryland!

The Party Authority in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware and Maryland!