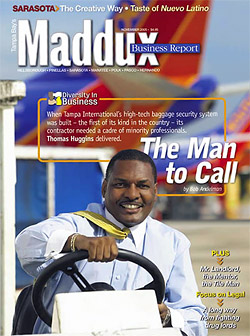

Thomas Huggins, founder of Tampa-based Ariel Business Group, featured on the cover of the Maddux Business Report. Story by Bob Andelman.

By BOB ANDELMAN

Written September 17, 2005

Maddux Business Report

Thomas Huggins knows people.

Construction people, engineers, environmental consultants, accountants, attorneys and all kinds of professional, small business people.

He’s made an entire business of knowing people, knowing people who know people, and knowing what some people are looking for in other people.

When governmental agencies and big businesses around the Tampa Bay area need to get a job done by a small, minority or disadvantaged business they often turn to Huggins’ 10-year-old Tampa consulting company, Ariel Business Group.

That’s what Skanska USA Building did.

When Skanska was preparing to bid on the design and construction of Tampa International Airport’s new outbound baggage handling system and security enhancements project in 2002, the general contractor knew that the Hillsborough County Aviation Authority required that a percentage of work on the system would be done by disadvantaged business enterprises – DBEs, in its bureaucratic lingo. (Other agencies and private companies may call them SBEs, for small business enterprises.)

“We understand that there’s more to dealing with a public entity than just building,” says Skanska Senior Vice President Jim Clemens. “You can’t follow a scorched earth policy in the local market. And there is a responsibility we have to support and understand the needs of the community. The taxpayers of this region have funded these projects. The taxpayer base is a reflection of those people in the community and therein lays the responsibility for an open-minded construction manager to ensure the work we do responds to the needs of the community. The original goal of the airport was 15 percent for this project. And we said, ‘We understand what you want to achieve.’ And we committed to a 20 percent goal right out of the chute. And we even beat that.”

Large government agencies maintain a list of certified DBEs in their area. The City of Tampa, for example, has a list of minority or disadvantaged businesses, as does the Hillsborough County Aviation Authority. The challenge for many general contractors who may not be based locally is that they are provided with a quantitative list of names and phone numbers but no qualitative information about each outfit’s capacity. Ariel Business Group – and similar consultants – adds value by providing missing background on firms they have worked with and their capabilities for tackling a particular task. Beyond that, they have often worked with additional firms that may not be on an agency’s list but that can perform a needed service.

“The outbound baggage project was a highly visible project, one that a number of firms were going after,” Huggins says. “I had a meeting with Frank Fralick, who was then the president of Skanska locally (and is now executive vice president of Manhattan Construction Company in Tampa). We talked about his desire and interest in pursuing this project and having a strong diversity of firms. He recognized the commitment of the Aviation Authority and he made a commitment to having a diverse team on this project.”

Huggins says Fralick made a decision to “do it the right way.

“There are companies that really believe they can get around the SBE requirement by filling out some paperwork and not achieving the intent of the program, which is why it was installed in the first place, to create opportunities where opportunities didn’t previously exist. Frank took the higher road.”

When Skanska won the baggage contract in mid-2002, Huggins and Ariel were immediately added to its team for the purpose of assigning $26 million (of the $130 million total budget) in subcontracting work. Individual contracts over the next three years ranged from $30,000 to $1 million. The baggage system was a design-build project that encompassed design, installation and construction.

“It wasn’t just bricks and mortar, either,” Clemens says. “It was high tech, very demanding. Our work couldn’t negatively impact aviation at Tampa International. It takes a special contractor. It’s like trying to build a new operating room at a hospital while there is an operation going on next door.”

What’s interesting is that Skanska USA Building has an office and presence in Tampa, unlike some contractors that may bid a project here but be based elsewhere.

“Do we turn to Ariel and a Thomas Huggins because we don’t know where to turn without them? No,” Clemens says. “We turn to them because they provide instant credibility in their community. They provide, in a real-time manner, which subs are capable – and which are not. Which are over capacitized and which are not. They bring a lot more to the table than a list of names. They understand the market and the firms available. Skanska knew of all these subcontractors before. Could we have done it without Thomas? Probably. But it would have made the job more difficult. He provides a service not unlike your insurance agent or attorney. He brings an expertise in an aspect of the market that we can’t provide on a full-time basis.”

Ariel started the process with a serious of informational meetings that introduced almost 40 minority and disadvantaged small business to Skanska and the dimensions of the project. Many had not worked for the airport or Skanska before. Clemens went through the project and provided background on Skanska and the scope and magnitude of the system. He also explained how, as a team, Skanska and Ariel intended to meet and exceed the Aviation Authority’s participation guidelines. (Not all the DBE firms went through this process but many did.)

Ariel had a continuing responsibility to the project from pre-start until closeout.

“We try to be proactive as opposed to reactive,” Huggins says. “We recognize the challenge of the larger firms. They inherently have budget issues and scheduling conflicts. We’re real cognizant of those issues. As we work with the disadvantaged companies, we want to be sure the DBE firms have the capacity to do their portion of the work. Being proactive, we want to ensure that we’ve covered the areas that potentially may be of concern: Can the company perform? Is there a need for performance bonding? Payment assistance? Our goal is to get the participating firms to look at (using DBE companies) as a process, not a project. They should be incorporated in the process of doing business.

“We not only are matching firms with capability,” he continues, “but we also are there to anticipate any conflicts, mediate any issues and alleviate problems. The goal is, get the project done, so everybody makes money and everybody walks away happy. This is business driven. The contractors are in it to make money. The subs are in it to make money. It’s only good in the end if everybody is happy. And that’s difficult to achieve in the construction business.”

Construction, as anyone who has ever hired a contractor for something as simple as a home renovation or as complicated as building an office tower, is a tough business. An awfully tough business.

“It’s a dog-eat-dog business,” says Huggins. “My passion for the subcontractors trying to enter it is you can be a great tradesman but you have to understand the business – the administration, the financial, the management aspect. All those components are critical in escalating your business. They’re critical to your overall success.”

The challenge for Huggins and his DBE network is in constantly upgrading not just their trade skills but also their industry savvy in ways that make them indispensable beyond earning set-aside project budgets.

“The majority of the minority subcontractor firms that worked on the airport project liked working for the contractor because of the relationships that developed,” Huggins says. “They were not easy contractors but they were fair; the contractors I talked to felt that. Skanska demanded performance; they demanded the best out of the subs. The subs respected them not only for being demanding but also being fair and respecting them.”

Clemens says the feeling was truly mutual.

“We got enthusiastic subcontractors that wanted to work, wanted to learn,” he says. “Because of that we achieved an even greater percentage than the goals for using disadvantaged businesses. We grew as a family on that project. All the ethnic and race divides withered away. Thomas and his leadership allowed that to occur.”

Skanska subsequently used some of the subs that Huggins introduced it to on other public – and private – projects in Orlando, Ft. Lauderdale and Miami-Dade.

The bottom line, of course, is the impact the DBEs have on the general contractor’s ability to profit from a job. But Clemens insists the equation isn’t that simple.

“Beyond the bottom line, we are helping to grow and cultivate in the Tampa Bay area a group of new and rising stars in the construction field,” he says. “We may not see immediate effects in economic aspects, but the market and community sees the creation of jobs and the stability of the competitive marketplace being improved. It isn’t all ‘Great Society’ stuff. It creates more qualified subcontractors, not just more qualified disadvantaged minority subs. These are newly confident people available to the airport five years out. The next group of subs will be stronger and better positioned as a result of these programs.

“My mission statement is to satisfy my customer,” Clemens continues. “My client is the Hillsborough County Aviation Authority. Their interest is that the tax dollars that they use to fund projects provides a benefit that transcends back to the community at some level. That is my job. Yes, we’re in business and business is capitalistic and there is a profit motive involved. But at the end of the day, the way I’m graded is on the level of client satisfaction that I bring. And I need to meet, at the most basic aspects, the goals my customer establishes for disadvantaged participation. I have it in a contract. For me to be profitable and not meet those goals, they won’t have me back.”

So what did the companies Huggins recommended do?

“A little bit of everything,” according to Clemens. “We had contractors that installed the baggage conveyor systems. We had electricians, welders, plumbers, excavators and underground utility providers. It wasn’t a bunch of guys who pushed brooms and threw out the garbage.”

And not only was the baggage system completed on time in April 2005 and work well, it won a major industry award. The National Construction Management Association of America gave Skanska its 2005 Project Achievement Award in the category of “Public Project with a Construction Value Greater than $100 million.”

“It’s a fantastic honor,” Clemens says.

• • •

Thomas Huggins gets high marks from everyone with whom the Maddux Business Report spoke. Huggins, 45, is a past-chairman of the Tampa Urban League and current chairman of the Hillsborough Community College Board of Directors, having been appointed by Gov. Jeb Bush in 1999.

He truly is a people person.

“He’s just a real easygoing guy,” says Mary Hall, legal affairs director for the Tampa-Hillsborough County Expressway Authority, another Ariel client. “And he’s got a good team. In all this time, I’ve never seen him not have a suggestion or a solution. He’s a good team player.”

That view is echoed by Skanska’s Jim Clemens.

“Our relationship has grown to be very friendly,” Clemens says. “We went from working associates to friends. He’s a great guy, hard working, whose career reflects his personality and work ethic, which is refreshing in the construction business. He has a very high threshold for dealing with difficult situations.”

But what is Huggins actually like as a man?

He’s been married for almost 20 years to his wife, Belinda, with whom he has two sons and two daughters. The oldest son plays football at The Citadel.

“Thomas is a pretty good guy,” says his friend of six years, Rea Remedial Solutions, Inc. President Kevin Simmons. “When I started my business – I used to work for Westinghouse and decided to open my own environmental firm – I met Thomas. Our firm was getting qualified to work for DOT through its bonding program and Thomas was running that program through Florida A&M University. I took the certification course through Ariel in St. Petersburg and Thomas taught the class. After I got certified by DOT, I came back and taught some classes for him. He gave me the old pitch about giving back. Thomas is good about being sure that those people who get help getting a leg up help the next guy.”

Simmons, who is African-American and the majority owner of his Valrico-based environment construction and engineering and assessment firm, has since worked on two projects referred by Ariel at Tampa International Airport, one for Skanska and one for Beck. He is currently working on another Ariel arranged assignment, the Selmon Crosstown Expressway expansion.

“Thomas has been a real proponent for minority business,” according to Simmons. “He’s done a real service in terms of helping small and disadvantaged businesses establish themselves through the cities, counties and state. He has a heartfelt view of helping and it comes out. He has made some introductions for us. By being the liaison for Beck and Skanska, it’s his job to understand the capabilities of those businesses. Once he knew what we could do and what they need, he was instrumental in getting us that introduction. “

Okay, okay, he’s a great humanitarian. But what’s he like?

“To be honest with you, Thomas is kind of a dry guy,” says Simmons. “There’s no wild side, no wild story to be related. He’s very into politics; he’s an African-American Republican. And he’s proud of being able to say it. A lot of African-American Republicans keep that to themselves.”

• • •

Like a lot of successful businesspeople in the bay area, Thomas Huggins relocated to Tampa from somewhere else; in his case, it was Charleston.

Huggins, who is originally from Green Cove Springs, Florida, received a degree in business and finance from the College of Charleston, SC, where he also played basketball.

Arriving here, he spent his first days working in the payroll accounting department of Hardaway Construction during its construction of the new Sunshine Skyway Bridge. Nights he worked for the St. Petersburg Times in it printing plant, folding and processing newspapers.

In 1983, Huggins was hired by Community Federal Savings & Loan, the only African-American, multicultural bank in the city at the time. From there, he worked for consulting firms such as Boone, Young & Associates and Laventhol & Horwath doing small business consulting. At each firm he worked with the U.S. Department of Commerce.

“During that time, we worked a lot with small businesses, particularly construction companies, on major projects in the area,” Huggins says. “We worked on diversity issues, primarily business related, and minority business development programs. We were versed in the procurement and contracting arena and some of the challenges minority businesses were facing at the time.”

Huggins’ responsibilities included assisting small businesses with financing, developing business plans, and obtaining financing through the Small Business Administration and local banks. “We were identifying contracting opportunities for small businesses with the government and private sector. We educated them on the procurement systems and entering the construction arena. At the time, I managed a five-person staff that provided those services,” he says.

Fees at both consulting firms paid by small business clients were offset by the Department of Commerce’s Minority Business Development Agency. The idea was giving small, disadvantaged and minority businesses a better opportunity to compete for both jobs and access. “DOC’s goal was to have an avenue where minority business would receive technical assistance to promote business development,” Huggins says. “They wanted them to get the same assistance offered to mainstream firms through CPA firms. That is otherwise prohibitive to small business, so the DOC contracted with firms to provide that assistance at a subsidized rate. So instead of $200 an hour, the firms that came in might pay $100 or $75 an hour.”

As it turned out, the DOC indirectly subsidized Thomas Huggins’ future as well.

“I gained a tremendous amount of experience,” he says.

No surprise then that when Boone closed its Tampa office in 1996, Huggins went out on his own and hung a shingle as the head of Ariel Business Group.

“I felt that there was a niche, a void, in the area as it relates to the emerging business market,” he says. “Businesses that are under $2 million in revenue needed managerial and organizational assistance, all the way down to individuals that were micro-businesses in needed of assistance in starting a business.

“And,” he says, laughing, “I needed a job.”

Huggins felt it was the right track for him; when Boone shut down, he didn’t apply for any other jobs with existing firms. “This was the direction that I was led to go,” he says. “Being a spiritual man, this is where my prayer was. I asked for direction and guidance from God and this was the direction that he led me.”

Seems logical. But when you say you’re a “consultant,” there are a lot of consultants that do a lot of things. To provide some credibility early on,

Huggins’ goal was not just be another consultant working from home, going from one client to another.

“I wanted to develop a business,” he says.

In the early days, Ariel consisted of Huggins and a part-time administrative support person. Today, he still runs a lean operation, helped by a vast computer database and a staff of five, including Melanie Mitchell, who was the project manager on the airport and expressway jobs.

“Relationships are important,” Huggins says. “The real issue for us is understanding the needs of the client, understanding the individual finance-making industry and what their likes and dislikes.”

Over time, Huggins broke Ariel up into three service areas:

• Management, advisory and program administration services;

• Corporate and diversity training to senior level management and governmental agencies – “We’ve not only worked for government agencies,” Huggins says, “but they’ve asked for our help on the public policy side to develop minority policies”;

• Work with individual firms to do contract compliance and small business outreach on construction related projects.

“On the emerging business side,” Huggins says, “we still work with individual small businesses with revenues below $1 million that seek assistance in procurement and understanding the government bureaucracy, as well as individuals seeking financing.”

Ariel’s annual revenues are in the “mid six figures” according to Huggins. He bills clients by the hour for services rendered, using the same time-tested approach as lawyers and accountants. The amount is not, he emphasizes, based on the DBE budget for a project. And Ariel does not charge the SBE firms it introduces to its clients. “That’s considered double-dipping and I wouldn’t do that,” Huggins says.

His goal, he says, is to see his small business clients outgrow him.

• • •

The Tampa-Hillsborough County Expressway Authority – the government agency that operates the Lee Roy Selmon Crosstown Expressway and the Veterans Expressway – hired Ariel Business Group as its official small business enterprise authority for construction of the new $400 million expansion of the existing Selmon Expressway. It was one of several consulting firms that responded to an RFP for an SBE consultant.

“We were centered on getting as much of the construction work distributed to small businesses as possible,” explains the Authority’s legal affairs director Mary Hall. “We’re a small agency. We couldn’t by any stretch license or register or maintain an independent contractor list the way city or county do. Our board decided that if a company is on the list on any governmental agency in a seven-county area they could be on our database. Ariel was hired to try to get the word out that these jobs are available through the authority and they’ve been pretty successful.”

As it did with the airport project, Ariel participates in weekly expressway construction meetings with the major contractors to keep abreast of performance and evolving needs.

“The firms say, ‘Over the next two weeks we’re working on whatever.’ Then Ariel goes back to their database and tells companies what is coming up this week,” Hall says. “The small companies wouldn’t have known about us because we’re not typically in the construction business. They can’t bid these huge jobs; they have to be subs.”

Ariel impresses its clients on both ends by staying involved in the process.

“Sometimes they come up with issues we don’t hear about, such as delays in payment,” Hall says. “They act as the SBE’s representative and they get through some sticky issues that always resolve satisfactorily. One time, for example, there was a delay in payment to a sub. That’s a hardship. Once the general contractor confirmed the work was satisfactory, we expedited payment to the sub based on Ariel’s intervention. They work closely with our project accountant. That’s how they track the SBE participation. We have a reporting system that involves everyone.”

The Expressway Authority requires any contractor with which it does business to follow its SBE policy. “Whenever they have any work effort, they’re encouraged to look for SBE firms. Our construction policy requires that the contractor have a similar policy to ours; most of them already do,” Hall says. “We don’t just say it and let it sit on the shelf. We require they participate.”

• • •

There’s something different about Thomas Huggins from other small business enterprise consultants that Jonathan Graham has worked with before.

“He’s professional,” says the Graham, of Horus Construction Services in St. Petersburg. “I’ve dealt with Thomas for about four years. We had an opportunity through him with the Hillsborough County school district. We also worked with him on a Palm Beach contract.”

The mark of an effective SBE consultant is that the agency or company that hires him or her has the power to enforce participation.

“If they’re just there as a show – ‘We, as a corporation, do outreach but the construction managers do what they want,’ there’s no value,” Graham says. “But if they want to take the advice of the consultant, such as Thomas, it’s a good thing. But we’ve found people want to work with people they know. Big companies know majority subcontractors. They don’t know minority contractors. People put up a front, ‘We’d like to work with minority contractors’ but they don’t know them and don’t take chance to get to know them.”

Kevin Simmons says that when it comes to opening his network, recognizing or seizing opportunity, Thomas Huggins doesn’t see people of color, sex or ethnicity, just opportunity.

“He’s been a real incubator for getting women-owned or (non-disadvantaged) small businesses started. He’ll say, ‘Here’s a good accountant.’ Or they say. ‘Thomas Huggins from Ariel said to see you.’ Or Thomas will call in advance and say, ‘This guy is coming to see you; he needs help.’ It’s a nice little network.

Ariel Business Group Website

(This version of the story may be somewhat different than the published version.)