(NOTE–We heard the sad news tonight that legendary Tampa businessman, baker, boxing promoter and entrepreneur Phil Alessi died today, Sunday, May 6, 2018. I dug into my archive for this extensive profile I wrote about Phil, published in Tampa Bay Life magazine’s June 1989 issue. There will be a lot of tributes to Alessi–a man I interviewed many times over the years–but few will have quotes from George Steinbrenner and a prescient reference to Donald Trump. Alessi was always available when I called and I will always treasure the time I spent with him.–Bob Andelman)

By Bob Andelman

October 31, 1988

At last, upscale grocer Phil Alessi’s greatest secret can be revealed: His wife shops at Simon Schwartz Supermarket, not the Alessi Farmers Market.

That’s not all. Drew Alessi has even talked to her ever-acquisitive husband about adding the neighborhood supermarket to his own stable of food stores.

“I told him once that Simon Schwartz was having trouble, that he should buy it and I’d run it,” says Mrs. Alessi.

Alessi didn’t bite at that opportunity, but the owners of Simon Schwartz would be wise to occasionally look over their shoulders. Phil Alessi is gaining on everyone.

•••

The latest surge of Phil Alessi’s entrepreneurial activities began in July 1987 with the opening of the Alessi Farmers Market in Carrollwood. Where else could you find

— and sample — angel hair pasta, kiwi jam, handmade sausages, unusual cheeses, wines, salad dressings and Phil’s favorite cannolis? Alessi claims to sell more fresh fruit and vegetables than any 20 supermarkets. And he says his seafood manager has saltwater veins.

“This operation would do well in the jungle,” boasts the 45-year-old businessman. “People would still come.”

When Phil Alessi and Mickey Duff had closed circuit rights to the Tyson/Spinks fight, New York Yankees owner George Steinbrenner changed his plans from seeing it ringside with Donald Trump in Atlantic City to hosting a private party for 100 at Malio’s in Tampa. Tampa Tribune Sports Editor Tom McEwen, who watched the short fight sitting between Alessi and Duff, later wrote a column about evening.

So successful and popular has the market become that when the city of St. Petersburg was searching for catalysts to return the glory to its downtown Pier, it turned to Alessi (and to Cesar Gonzmart, owner of the Columbia Restaurants).

Smart move. The Pier in August and drew 500,000 people in its first month and the Alessi Cafe, daiquiri bar, bakery and other food outlets there turned a profit after just five weeks. (The farmers market took more than a year.)

Suddenly, farmers markets are the cure for what ails cities all over the Tampa Bay area. There’s a deal in the works to bring Alessi’s market to downtown Tampa as part of a restaurant/nightclub complex. Brandon, Lakeland and Palm Harbor have extended similar opportunities. Alessi and concert promoter Jack Boyle (of Cellar Door Productions in Fort Lauderdale) want to build an amphitheater at the Florida State Fairgrounds. And he wants a greater presence in downtown St. Petersburg, possibly on the ground floor of the under-construction Barnett Tower.

In the meantime, Alessi plans to re-invent the main Alessi Bakery on Cypress Street in Tampa. It already operates seven days a week, 24 hours a day and has 120 employees who prepare breads, rolls and pastries for 150 wholesale accounts including Holiday Inns and the Specialty Restaurants chain. But Alessi, who owns the block across the street (he used to live there), proposes to build an enormous bakery/deli on the site, something like Wolfie’s in Miami Beach.

•••

Business is booming for Alessi. But personal setbacks have cast a long shadow over his successes.

Particularly painful was the September arrest in Tampa of his eldest son, John, on charges ranging from racketeering to trafficking in cocaine and marijuana.

John, 25, one of four Alessi children, was arrested on evidence gained through a court-authorized wiretap. He was one of 24 people picked up on similar charges, although John was described as “the central figure,” according to a Hillsborough Sheriff’s Department spokesperson. He was recorded on the telephone allegedly discussing drug deals from Miami, St. Petersburg and Ruskin to Chicago, Raleigh, N.C., and Short Hills, N.J.

Bail for John was initially set at $1.3-million, later reduced to $120,000. But Phil Alessi said no. He would not pay “10 cents” to bail out his son until John expressed remorse over his actions.

“Somebody needs to kick his ass, make him wake up,” Alessi sharply tells his lawyer on the phone, several weeks after John’s arrest. “Maybe it’s time he gets acclimated to that environment. Open his eyes.”

So for more than a month, John Alessi sat in jail.

“He’s had trouble with the law in a lot of things,” says Alessi, following his telephone conversation. “Four years ago, I told him that if he ever got in trouble with the law that was drug-related, I would never help him. … My ex-wife said, ‘What are people going to think?’ and ‘How embarrassing.’ I don’t care. It doesn’t matter what it does to our business, it doesn’t matter what they think of us. What matters to me is John. I love him — he’s my son and I’m going to do the best thing for Johnny.”

John has been arrested nine times since 1982 on charges ranging from driving with a suspended license and possession of drug paraphernalia to strongarm robbery, possession of cocaine, aggravated assault with a firearm and resisting arrest with violence. This is his first time behind bars. (In other cases, charges have either not been filed or he has been given probation or community control.)

People who know him call John Alessi “Mr. Personality.” His stepmother, Drew, says that John is “absolutely delightful.”

“But he doesn’t have a whole lot of depth,” she adds. “I used to tell Phil that what terrifies me about Johnny is, he’s not immoral, he’s amoral. We have an 8-year-old. If (John) had ever offered (drugs) to his brother, I’d be on him with all fours. That really frightens me.”

Of Alessi’s other children, Dina, 23, runs the Alessi Bakery on Cypress. Phil Jr., 21, oversees the bakery at the Pier. John, Dina and Phil Jr. are from Alessi’s first marriage. He married Drew 14 years ago and they have one son, Jason, the 8-year-old.

Only John has given the family cause for concern.

“I can sit down with Johnny for four or five hours and he’ll explain things, why he did ’em,” says Alessi. Then his son will insist he’s going to get a frest start, get on the right track. “He’ll say, ‘Yeah, Dad, but I’m not going to start this Monday. I’m going to start next Monday because this week I’m going to a concert in Miami.'”

Father and son had a deal last spring where Alessi would back John in a business to manufacture and sell cannoli shells on the wholesale market. After three months, John lost interest. He worked sporadically in the farmers market, but was frustrated that he was expected to work his way up from the bottom and not receive special treatment as the boss’ son.

“I tell Johnny that I find it ironic that your brother and sister came out of the same environment you did. So let’s stop making excuses. Look in the mirror and say, ‘I, John Alessi, am the reason these things happen.’ When you do that Johnny, then you have a start on being an asset to society. Until that time, son, you’re not ever going to be a success.”

•••

Last summer, Phil Alessi had problems of his own.

The New Jersey Casino Control Commission questioned his familiarity and contacts with the late Santo Trafficante Jr., alleged to be the head of organized crime in Florida until his death. They used Alessi’s visits to Trafficante’s home — despite the baker’s steadfast insistence that he was simply delivering cannolis to a sick friend — as a reason to deny Alessi’s bid to promote boxing in Atlantic City.

“That was bullshit,” says Mickey Duff, a British boxing promoter who also manages John “The Beast” Mugabi and has co-promoted more than 25 bouts with Alessi. “To attach him to crime is ludricrous. He’s not short of money. His income is visible, not invisible.”

Alessi’s first response was to let the issue drop. “It was a very innocent sitution, a situation that I was insensitive to,” he says. “I’d known Santo for 25, 30 years. My impression was that he admired what I did. That was genuine. I never recognized him as the character he was. He was a very kind man, always saying to me, ‘Never get involved with undesirables.'”

It was Duff who convinced Alessi to fight for the New Jersey license.

“I told him, ‘It’s a slam on your character,” says Duff. “He was getting a bum rap. If you walked into an Atlantic City casino and shot off a gun, it’d be even money you’d hit a gangster.”

“It wasn’t a matter of the license anymore,” says Alessi, “it was my integrity that was questioned. You talk about my family, gosh, they’ve all worked hard. I wasn’t going to let them take away from that. They said I’ve dealt with guys in boxing that were associated with the mob. What the hell do I know? A guy might (manage) a boxer, the guy fights for me so I pay the guy. They tried to create a scenario … It’s stupid. They were really pulling at straws. They came down here and scrutinized my whole life. The scrutinized my bankers, they went into my safety deposit boxes, scrutinized every company I have. They tried to associate me with drugs because I’m in the fishing industry and I have my own boats. Now, isn’t that ridiculous? I’m not hiding anything.”

On the strength of depositions from Tampa beer distributor Art Pepin, former FBI special agent Phil McNiff, Santo Trafficante III, nephew of the reputed mafioso and Tampa Tribune Sports Editor Tom McEwen attesting to his good character, Alessi was awarded the license he sought.

“He’s a friend of mine,” says McEwen. “I was surprised that so much was made of it. He works his ass off.”

•••

Alessi got interested in boxing by going to closed- circuit TV bouts with his father. But partner Duff thinks that being a boxing promoter appeals to Alessi on a much different level than making money or simply being a fan of the sport.

“He likes the limelight, as all entrepreneurs do,” says Duff. “You can open 10 stores and nobody will know you’re alive. But you make somebody an offer of $1-million to fight

somebody and hold a press conference, you’ll be in all the papers.”

•••

To look at Alessi would not bring thoughts of pro boxing to anyone’s mind. He’s a big man, of course, 6-foot-3 and 235 pounds (down from 300 a few years ago). But there’s no

doubting he grew up on a cannoli and Cuban bread diet although he’s no longer the fat, hustling kid with the big mouth a lot of native Tampans remember from his youth.

“I try to watch myself because I do a lot of sampling to get a true taste of something that’s special,” says the admitted foodaholic. “Whether it be any creative formulation — a steak sandwich, brittle — I’ll taste it.”

Dinner with the Alessis is usually found on the road. Since the days when Drew was involved in day-to-day business, before Jason was born, they have rarely supped at their modest Spanish-style home in Palma Ceia.

Drew and Phil met in 1971 when he owned a nightclub called King Arthur’s Lounge in Tampa and she worked there as a cashier. They married 2-1/2 years later and although the honeymoon was hardly romantic, it was pure Phil: “We spent a week in New York looking at bakery equipment,” recalls his bride.

In the early days, Drew played devil’s advocate to her husband, the eternal optimist.

“Everything can’t be that good,” she’d tell him. But usually, things went Alessi’s way. “Now I don’t need to play that role.”

•••

Notes on Phil Alessi:

He is a registered Democrat.

His friends include Tom McEwen, restaurateur Bern Laxer, developer Dick Beard and automobile dealer Frank Morsani.

He often describes himself as “retired.” According to his wife, that means the business day starts at 7 a.m. instead of 5:30. It still ends after 6:30 p.m.

He’s a lousy, nosy restaurant diner, always poking around in the kitchen, looking for new recipes and asking about volume. On the other hand, friends say he picks up checks faster than anyone else they know.

Relaxation comes on a fishing boat off Cortez every Friday afternoon with friends and family. Exercise comes occasionally on a stationary bike at home.

When he wants to get your attention or make a point, he flails his arms, slapping at the intended listener’s arm.

One of four children, he is the only one who doesn’t have a college degree. Two of his sisters — twins — are school principals. The third is a teacher. His brother is a pharmacist. Phil dropped out of Tampa Jesuit High School.

His automobile of choice is the Lincoln Town Car. He drives it about 40,000 miles a year going back and forth between his businesses.

He’d rather watch a good boxing match than eat a Napoleon, but with cannoli, it’s a close call.

•••

Alessi’s taste buds were educated long ago to know good from bad. His grandfather, Nicolo, began baking for the people of west Tampa in 1925. The work later fell to Alessi’s father, John, and his brothers and sisters. The Alessi Bakery business grew over the years, but nothing like it would when Phil bought out the family in 1972 at the age of 29.

Before that happened though, Alessi had a lot of living to do.

As a teen-ager, he spent a summer vacation at Clearwater Beach catching and selling pinfish for bait. (He now owns nine commercial boats and sells 100,000 pounds of grouper and snapper per month). After quitting school, he hit the road with pal Sam Costa, bowling over local yokels.

“We made a lot of money. Sam was the bowler — quiet. I was the big mouth, the promoter, braggish, carrying the big bag of money that everybody wanted to take away,” he says.

(The two now share ownership in a West Palm Beach bowling alley and plan to build one in Tampa. Alessi has a 190 bowling average.)

Returning to Tampa, Alessi and another pal, Rico Urso, promoted concerts by Al Green, the Drifters and others.

“We brought the original Drifters into the old Palladium Ballroom,” he recalls. The ballroom was not far from the site of what is now the Tampa Bay Performing Arts Center. “That was a Saturday and it was the first concert I ever did. Sunday, we went out in the woods, Thonotosassa. Thirty years ago, that was the sticks. We had a joint pack-jammed. All of a sudden there was a raid — they were selling moonshine in the back! So Rico gives me a bag of money and a gun and he says, ‘Anybody comes in that door, shoot ’em!’ ‘My God,’ I said, ‘Anybody comes in that door I’ll probably shoot myself.'”

(Alessi Promotions had a piece of the action when Frank Sinatra, Liza Minnelli and Sammy Davis Jr. played the USF Sun Dome last fall.)

•••

Phil Alessi could never be satisfied with just one business.

At 18, he opened his first bakery independent of the family — Phil’s Bakery. Then came several Cakebox Bakeries and independent sandwich shops. Along the way he developed the interest he and his father shared in boxing into yet another career: boxing manager, promoter and gym owner. (The last Alessi Gym closed in October.)

At 27, he announced his intentions of being a millionaire before he was 30. He was.

When Alessi took over the old family operation, he changed his own stores’ names to Alessi Bakeries. Fire closed the original bakery in west Tampa and Alessi made the Cypress store his main location. He later closed the smaller outlets, a precursor to the development of the Alessi Farmers Market in Carrollwood and Pier shops in St. Petersburg.

In addition to all these businesses, Alessi also manufactures rum balls for a mail-order company in Wisconsin, wheels and deals in real estate, builds boats, has the concessions rights at the USF Sun Dome and Florida State Fairgrounds, promotes tractor pulls and monster truck shows across the country, has exclusive rights to closed-circuit televised boxing in Florida (the Mike Tyson-Michael Spinks bout grossed $2.3-million), sells boxing packages to the USA Cable TV network and represents a growing stable of professional athletes, including local baseball stars and Olympians Ty Griffin and Tino Martinez. He employs nearly 800 people.

New business ideas occur to Phil Alessi faster than Mike Tyson can swing his fists. “Phil works so fast, he may have had two or three meetings on something and he’ll come to me and say, ‘Here we go,'” says Rudy Rodriguez, the man whose job it is to track and organize the ever-growing Alessi empire.

“A lot of times,” says Alessi, “I’m involved in 10 meetings a day and they’re all different. I have to get adjusted to every one of them: the bakery department, the bottom line in the meat department, creativity in the concession business, whether to send our boats to Santo Domingo. The people I deal with in our boat business aren’t interested in the bowling alley. The people in the bowling alley aren’t interested in the festive marketplace and the people in promotions aren’t interested in the farmers market. I have to keep everything in perspective.”

•••

To every successful man, there are limitations and Phil Alessi has a few. He’s nearsighted. He’s a diabetic. And he has learning disabilities that have made reading and writing a tremendous chore.

“I’ve never written a letter in my life. I might mess up my grammar or something. It doesn’t matter. But if you’re trying to be perfecto, you let somebody do it who’s good. I have people who can write some of the finest letters on earth,” he says.

Asked if he reads much, Alessi says he listens to tapes of authors reading their books aloud. That’s where he learned about J.C. Penney, Henry Ford, Harvey Firestone, Bill Lear and

Albert Laske.

“I used to read things four or five times to make sure” he understood them, admits Alessi. “Some people can read things one time. Things that are very important to me, I want to make sure I comprehend it right. I’ll read it again. I do what it takes to make sure I understand exactly what I’m reading.”

Rudy Rodriguez, Alessi’s right-hand man, was unaware of his boss’ specific learning disabilities.

“You know, as far as writing business letters, I can’t say. Part of my job is to handle his business correspondence. If he had lunch with George Jenkins (founder of the Publix Supermarket chain and an Alessi hero), he’s not going to write a letter, he’ll pick up the phone and say, ‘George, I had a great time.’ He’s on the phone constantly,” says Rodriguez.Part of Rodriguez’s job is to boil down contracts to the real nitty-gritty.

“He likes to cut through the B.S. of a three-page contract,” says Rodriguez. “He’ll say, ‘Rudy, what does this mean to you?'”

•••

Almost daily tours of the bakery, farmers market, Pier and fairgrounds give the entrepreneur a chance to see and be seen.

Employees — and there isn’t one he doesn’t seem to know by name — get greeted with a “Hiya, Ed, how we doin’?” It’s a cheery Southern familiarity and pleasantry.

On a recent inspection of his operation at the St. Petersburg Pier, Alessi is introduced to Arnold Breman, who is having lunch with his family at the Alessi Cafe. Breman, director of Ruth Eckerd Hall in Clearwater, is ecstatic.

“I shop at your place all the time,” says Breman, referring to the Tampa farmers market. “You have to open a place in North Pinellas.”

Alessi tells Breman that he has talked with developer Charles Rutenberg about doing just that, although nothing is firm. Then Alessi turns the tables, complimenting Breman on

his facility and says he’d like to promote some concerts there. The two exchange cards and promise to get together soon.

Later in the day, walking through the farmers market, Alessi talks about creating synergy among his employees and about creating “win/win” opportunities for himself and his business partners.

“Win/win is longevity,” he believes. “When you make money with people and they make money with you, they keep banging at your door. There’s opportunities coming to us every day that, when I was young, I’d give my right arm to have. Today we turn ’em down. We don’t have time.”

He points to the olive salad in the deli and notes that it comes from his aunt’s own recipe. And that he was making deviled crabs when he was 8.

In the bakery, time stops.

“I still love the bakery as much today as when I was 6 years old. It still smells good. … I still create things. I go to my people and I say, ‘This is what we’re going to do.’ They don’t tell me any more that they don’t think it can be done. I’m pretty convincing.

“They know that I know every product,” he says of the people working in this department. “If something is wrong, they know that I know who is responsible. I can look at every product we have and evaluate it immediately.”

Alessi’s advice to newcomers at the market bakery is to try Robert Jorge’s cakes.

“He’s got this flair,” says Alessi. “He’s — I guess — a replacement of me. He comes up with different things every day.”

Jorge says he’s learned a lot from the boss. “I haven’t met anybody who has such respect for quality,” says the master baker. “He knows exactly what he wants, how he wants it.

“When he’s in doubt about certain things, he samples,” adds Jorge. “And when there’s something that looks good, he’s there, believe me.”

•••

George Steinbrenner was introduced to Phil Alessi several years ago by the Tribune’s Tom McEwen. It seems that the owner of the New York Yankees and chairman of the Board of American Shipbuilders in Tampa had the closed circuit television rights to a couple of Muhammad Ali fights late in the champ’s career and McEwen suggested to Steinbrenner that he give this young fella Alessi a shot at co-promoting.

“Pretty soon,” says Steinbrenner, perhaps overstating the case, Alessi “became one of the biggest boxing magnates in the country.”

Last year, when Alessi and Mickey Duff had closed circuit rights to the Tyson/Spinks fight, Steinbrenner changed his plans from seeing it ringside with Donald Trump in Atlantic City to hosting a private party for 100 at Malio’s in Tampa. McEwen, who watched the short fight sitting between Alessi and Duff, later wrote a column about evening.

Put Steinbrenner in Alessi’s corner.

“I’m a great admirer of his,” says the Yankees owner. “I like guys who are doers. He sets his mind to do something and he does it — with quality. He’s in a city of doers and he is certainly right at the top of the list. He’s a fine young man.”

•••

Nicolo Alessi would probably have been surprised to see all his grandson has done in 45 years, making the Alessi name as well known and respected as any Lykes, Ferguson, Thayer or Gonzmart.

He is one of a generation of young businessmen — Trump, Ted Turner and others — who have taken modestly successful family businesses and carried them in directions that previous generations couldn’t have dreamed possible.

“The heritage is something,” says Alessi. “I cherish that. When I was young, I hung around with a lot of kids who did a lot of bad things — drugs, stealing, breaking and entering. A lot of my friends did that. But the one thing that always kept me from doing that was my family. My mom and dad and his father and mom, his brothers and sisters worked so hard that I didn’t think I was entitled to abuse that hard work and reputation that they had.

“Now I feel that I have contributed to that reputation,” he says. “The good Lord has given me a knack. And he’s instilled in me ambition and the ability to do things nobody else has done.

“I love what I do. I’ve turned losers into winners by sheer persistence. I have a philosophy that you never lose until you quit.”

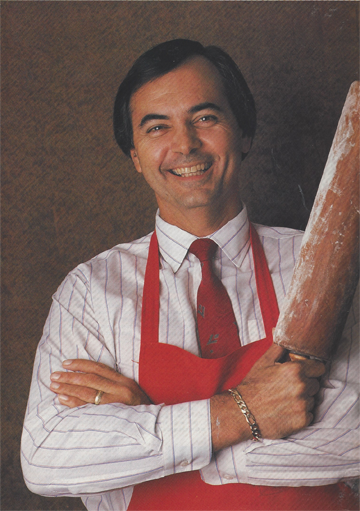

Phil Alessi (Photograph by Chris Coxwell for Tampa Bay Life)

Phil Alessi profile by Bob Andelman for Tampa Bay Life, June 1989