By Bob Andelman

Gainesville Magazine, 1980

It wasn’t had to assert yourself in the 1960s. All you needed were two things – a cause and a match. Men burned draft cards. Women, their bras. Students, the local ROTC building.

The sixties was, indeed, a volatile time, an era of almost unprecedented social upheaval and revolt. The issues are familiar: the Vietnam war, the eighteen-year-old vote, civil rights, legal abortions, to name a few. The fights were often violent and took place on a social battleground.

We had a name for those who went against the system. We called them radicals.

It’s only natural for issues to change over a twenty-year period. And they have. Black Panthers, a senior citizen’s lobby group. Students against the war are now Students Against the Death Penalty. The Gainesville Eight is almost forgotten; we now have groups like the Catfish Alliance.

Having a cause in 1980 is just s chic as it was in 1960. But a curious phenomenon has taken place. Railing against the system has become respectable. Many who were disheveled pickets and protesters long ago, are now established, three-piece suit professionals. And we have a new name for them. Yesterday’s radical is today’s activist.

These people fear the stigma of being branded a radical. And strangely enough, their fights occur within legal boundaries. They get permits for their marches. They take cases to court. They write letters to newspapers.

And today, if there are any matches being lit, it is under the feet of local politicians. The approach is different. But today’s activists get things done.

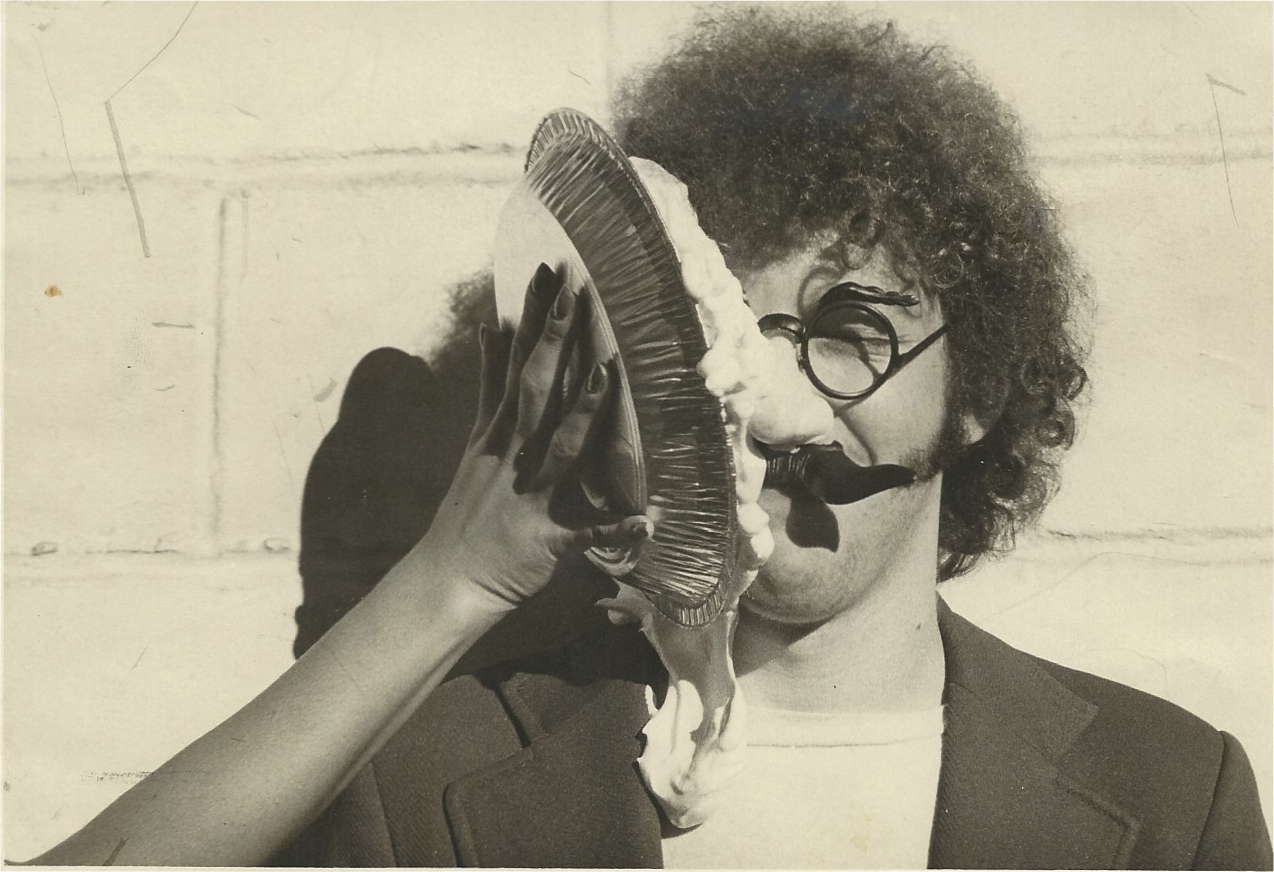

Gary Gordon, a local entertainer and member of the anti-nuclear Catfish Alliance, is the president of the newly-formed Citizens for a Non-Nuclear Future. CNNF is a splinter group of the Catfish Alliance, which was established in 1978.

At twenty-seven, Gordon has plunge deeply into his second major cause. A devout activist in the anti-Vietnam War movement of the early 1970’s, Gordon shares many characteristics with other individuals spear-heading causes in the 1980’s. Today’s activists are optimists and idealists, he claims, people who can mix their opinions with a pragmatic understanding of politics.

According to Gordon, there is a framework of four problems peculiar to cause activists:

Few people know there is a problem; activists feel something can and must be done.

Once confronted, people don’t agree on something being a problem.

People know there is a problem and don’t care.

People don’t see that an answer to the problem is possible.

“What we’re dealing with is not only letting people know, but helping to change their minds,” says Gordon.

“I take a lot of strength from the Abolitionist Movement. That feeling of knowing that something took forty years and wasn’t resolved. . . that can give you some sort of perspective.”

Mark Davis, twenty-five, editor of the Florida Non-Nuclear Network Newsletter and a founder of the Catfish Alliance, is probably least-known for his apparent work, the outside mural of the Lone Star nightclub.

The activism movement, Davis insists, “calls to the floor, once again, the question of who’s in charge, who’s making the decisions, how the decisions are made, and how these decisions affect people. That’s the case of the civil rights movement, the women’s movement, and one of the cores to the anti-nuclear movement.”

Davis also defends the composition of the anti-nuclear forces. “There aren’t any members who have any far-out spiritual or political views. They’re just people; we all have jobs.”

As for the born again anti-draft movement, time has taken its toll. A legal network formed at the height of Vietnam draft registration and evasion has now broken down into myriad of anti-military lawyers and military grievance counselors. In the advent of renewed registration it could be re-formed, but few (if any) barristers are giving up established practices in anticipation of its arrival. “There isn’t much we can do about registration until it comes,” says one.

The Coalition Against the Draft formed in late January after President Carter’s reversed position of favoring registration of nineteen and twenty-year-old American youth.

Jim Zimmerman plotted bombing targets for military intelligence during the 1960s. Enlisting immediately after high school in 1963, he began to hear government explanations of the Vietnam campaign which didn’t coincide with what he was doing, or what was going on. “The war was one big lie. It kind of turned my head around.”

After his tour of service in Vietnam, Zimmerman joined the Vietnam Veterans Against the War in his native Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. Zimmerman was involved in publishing a newspaper supporting Reverend Phillip Berrigan, who was accused of “conspiring to kidnap Henry Kissinger” in 1970. Amnesty and community criminal justice programs occupied Zimmerman’s interests until 1977, when he left Harrisburg for Gainesville.

Now thirty-five, Zimmerman has a draft-age brother. “They’re not going to tell him the same things and get away with it,” he says. “I’m going to continue to speak out and do what I can to change that.”

Gay Liberation, a noticeable community voice not too long ago, has slipped from easy visibility. A task force once operating at UF “deactivated” about nine months ago, shortly after its faculty advisor quit.

The management of the Oaks Six Theaters anticipated some gay protest over the recent showing of Cruising, a film which depicted Al Pacino a detective hunting a homosexual murder in New York’s heavy-leather world. No protest occurred, but the theater was prepared.

“We had a security guard here the first week, but I guess the gays here just don’t care,” muses an assistant manager at the Oaks.

(Gainesville Magazine was unable to locate a spokesman for the gay movement here in Gainesville.)

Students Against the Death Penalty, headed by Don Mackel, has had its share of times. Problems with University of Florida Student Government and the Gainesville Sun may have prevented the group from receiving the attention Mackel feels is warranted.

With the newspaper, “it’s a real Cold War thing. The Gainesville Sun has a real ban on covering anything that has to do with us.” Mackel admits, though, he is unable to point to any specific reasons for the “ban,” and the Sun (whose editorial position has long opposed capital punishment) denies the charge.

As for SG, “Who has time to spend with all these snot-nosed white kids arguing about things in a room and building we can’t even control?” Mackel asks.

The protest against capital punishment is, he admits, “crisis-oriented” often depending on an execution to increase public interest.

“We’ve been stressing the ongoing campaign. Within every execution there’s some kind of quirk. We want to keep pressing on that.”

The development of an organizational structure was a problem for this group, whose size fluctuates with time between executions. Five service coordinators now handle demonstration permits, press releases, and preside over meetings.

“Students are reluctant to protest,” says Mackel. “It takes a structure. If they feel they’re all alone, they’re not as prone to protest.”

Mackel recently took part in a march of more than 5,000 people in Greensboro, North Carolina. They were protesting the Klu Klux Klan, after KKK members allegedly shot five members of the Communist Worker’s Party outside a nearby factory.

Founded in 1972, the Gainesville chapter of the National Organization for Women will change presidents in April. Leaving is June Hain, leader since May, 1979, and entering is Sharon Bienert.

Hain, twenty-three, chose to become involved with the women’s movement because “I hate to see people sitting around complaining about things and not doing something. People like that frustrate me.”

Student apathy was one of the most frustrating blocks for Gainesville NOW, which operates out of an office in the J. Wayne Reitz Union.

“A lot of students live for Frisbee and disco, and that’s about it. They don’t realize how much could be lost if they don’t get active.

“People don’t have to get as involved as I have,” says Hain, “but every little but helps.”

Looking at NOW retrospectively, Hain notes the difference between the local and national organizations lie in emphasis. In Gainesville, communication can be a problem as people join for a year and then move on. The middle-class orientation of national NOW has “missed out on a lot of traditional women,” such as secretaries and nurses, says Hain, who believes the group should further spread it scope to include student activists.

President-Elect Sharon Bienert, twenty-six, argues that local communication is a problem in Gainesville. “Townspeople feel that what NOW is doing isn’t real. I think that’s a sad mistake.”

Bienert, like Jim Zimmerman, fought against the Vietnam War from Pennsylvania. Her battleground was Lancaster; her friends were Quakers. She spent the mid-Seventies in Europe, but Bienert carried her activism along, fighting for various Third World causes.

“If we don’t change society, it’s going to be hard to survive in the future,” she says. “I don’t think we can separate the issues,” she says. “That’s real apparent with the draft.”

NOW, due to the Carter proposal to draft women, has often demonstrated side by side with members of the Coalition Against the Draft, and Bienert notes that crossovers between the two groups are not uncommon. Bienert also point to an individualistic aspect of group movements like NOW and CAD.

“If people stop noticing you,” she says, “some people drop out.”

Of course, not all activists maintain top positions in cause-oriented groups, and not all have the time to make a part or full-time careers out of political involvement.

Twenty-two-year-old Keith Wolff, for example, feels there’s a strong need for people like himself in the Environmental Action Group at UF. “Whether it be five minutes a week or twenty hours,” Wolff sees himself and others capable of making useful contributions despite time restrictions.

An interest in camping and hiking moved Wolff to join EAG.

“Sometimes I feel I should be more involved than I am,” he says, “but I don’t tend to be moved to a cause because it’s a cause.

“Some people are just naturally drawn to causes. There will always be people protesting something. . . they’ll scream before other people scream.

“I hear the screaming getting louder,” says Wolff.

Dr. Mac Steen, a graduate of the Emory University School of Dentistry, was uninterested and inactive during the heyday of Vietnam protests. Busy with football, Steen admits now he was “just along for the ride in those days.”

After graduating from Emory, Steen and his wife joined the Air Force and spent four years in Europe. Returning stateside in 1978 was “quite a shock” for the Steens. They took an interest in the anti-nuclear movement and joined the Catfish Alliance in its infancy.

“We all took on assignments to educate ourselves. I took on Crystal River, partially because I was actually considering setting up a practice down there, but I was a little concerned about the nuclear plant,” says Steen.

Steen was further alarmed when he was given a tour of the plant. The company guide was hardly enthusiastic about safety procedures, and Steen lost his enthusiasm for the town. Shortly thereafter, Three Mile Island broke down, and Steen was cemented into the movement.

Today, Steen, like Keith Wolff, finds the demands on his time too great to continue the ten-twelve hours per week he had been putting into the Alliance. Four or five hours is now his average, mostly with Citizens for a Non-Nuclear Future.

Solutions to the problems which activists deal with in the Eighties will come from building up, not tearing down, institutions, most agree. The radical stance of the Vietnam era activists has been replaced by a pragmatism that runs through each of the contemporary movements.

Gary Gordon feels that talking, reading and writing are his key instruments. “I think it is important that ideas be put down.

“There’s a lot of reasons to be proud of this country. . . People are very eager to defend what they’re proud of, and sometimes that makes them very gullible,” says Gordon.

Stressing his confidence in the American educational and political institutions, Gordon is at odds over how long he will remain politically active.

“I don’t know if I’m always going to have the stamina to be as heavily involved as I am now, but once you develop a consciousness for this kind of stuff, it’s real hard (to quit).”

Gordon believes that long-term activists face the possibility of three brick-wall syndromes: burnout, disillusionment, and something he calls “co-optation.”

Burnouts suffer from the social work syndrome, he explains. They see poverty on a daily basis, and after several years they give up.

Greater militancy, Gordon claims, is often adopted by those activists who have found little satisfaction – or achieved solid results – through their current methods.

“Co-optation is another word for ‘bought off’,” he says. “People who were involved in President Johnson’s war on poverty are examples of this. The people leading the movement were hired by the government, turning into bureaucrats forced to defend a system which put bread on their own tables. These people felt a lost sense of idealism.”

Nonetheless, Gordon’s personal enthusiasm for political and social involvement hasn’t faded over the past decade.

“One of the greatest things you can do is to be an activist, to educate yourself to have opinions, and to speak out,” he says.

Don Mackel echoes the sentiments of many activists who cite the “screaming” they hear, and the coping they must do.

“There are so many pressing things right now,” he says. “You watch the news and you scream. For awhile there, I was so crisis-ridden. . . now it’s just something you wake up to and deal with.”

Keith Wolff points to his constant reading on environmental issues and smiles.

“Undeniably,” he says, “there are answers.”