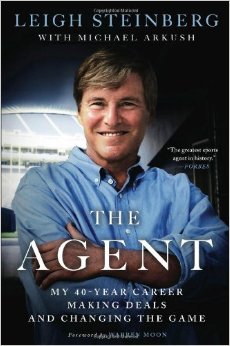

Order ‘The Agent: My 40-Year Career Making Deals and Changing the Game’ by sports agent Leigh Steinberg with Michael Arkush, available in print or e-book from Amazon.com by clicking on the book cover above!

By BOB ANDELMAN

(Originally published in Gallery Magazine, Spring 1994)

Vince Lombardi never met a sports agent he liked. Or one with whom he’d negotiate a deal.

According to legend, when a popular Green Bay Packers player showed up in Lombardi’s office with an agent to renegotiate his contract, the coach looked the outsider up and down. “Who’s this?” he asked.

“My agent,” said the player.

“Wait here.”

Lombardi disappeared into an adjacent room and was gone for about 30 minutes. When he returned, the puzzled player and his agent said they were ready to get started.

“We have nothing to talk about,” Lombardi said. “You’ve been traded to Washington.”

Agents and players in all four major team sports have changed dramatically since Lombardi’s day. The collapse of the reserve clause and rise of television, unions, collective bargaining agreements, collusion, salary arbitration and free agency have forever changed the leverage of athletes dealing with management.

Prior to free agency and salary arbitration, there were no real agents in baseball except for a superstar using a manager for his speaking engagement or endorsements. The reserve clause in baseball bound a player in perpetuity to a club. If an agent said he wanted $80,000 instead of $30,000, management said, “He can shovel coal! I control his destiny.” But when free agency and arbitration came into the picture, players needed somebody to prepare their case and negotiate. Free agency became a cumbersome process for players. They’d have to call around, make appointments, play one team against each other. Agents came on the scene and intervened almost overnight.

In the National Football League, it wasn’t until the collective bargaining agreement of 1975 that the right of representation was guaranteed.

“Up until then,” says Berkeley, Ca.-based agent Leigh Steinberg, “it was the Wild, Wild West.”

Steinberg, who represents more NFL quarterbacks – 23 – than anyone else and who negotiated five football deals in 1993 alone worth $80 million, leads the life other agents dream about. For one thing, he’s made quite a handsome living by consistently signing the best pigskin talent straight out of college. For another, he’s almost as famous as some of his players.

He’s not the only agent whose reputation made him a recognized name in sports household. Others include David Falk (Michael Jordan’s man), Jim Neader (Dwight Gooden) and the late Bob Woolf (Larry Bird). But despite their renown and success, there’s debate over the impact they’ve had on the games themselves, good or bad.

“I think they’ve had an enormous effect,” says Orlando Magic General Manager Pat Williams. “Over the last 20 years, they became the comparable businessmen to the owners on the other side of the table. It’s not the players – the agents control everything that happens on the other side of the table. Their job is to drive the toughest bargain they can.”

NFL Players Association Executive Director Gene Upshaw steered his players union through the legal morass of the reserve system during the late ’80s and into the promised land of free agency. But he doesn’t rank agents on his list of the high and mighty in sports.

“Their power and influence is in their clients,” Upshaw says. “And they can’t operate unless we say so. No agent ever obtained free agency. The union did. And no agent can make a player better than he is.”

Early on, the agent field was full of unaccredited shysters, eager to scam a few thousand bucks off unsuspecting, uneducated, athletically gifted youngsters. Today, player representation is a higher art, characterized by stable, recognizable faces and typically controlled and certified by the player unions. In the NFL, in fact, clubs are restricted by the new collective bargaining agreement from negotiating with any agent who has not been certified by the NFL Players Association.

Of the four major leagues – NFL, NBA, NHL and Major League Baseball – only the latter has yet to require agent certification. No doubt it’s coming.

“I am not anti-agent,” Pat Williams says. “The good ones are good for the game. They know what they’re doing, they know the industry. They’re doing what they have to do. Could the player do it alone? No.”

o o o

Twenty years ago, average player salaries in sports were stuck in the low five figures. The concept of New England Patriots QB Drew Bledsoe signing a $4.5 million bonus the day he joined the Patriots didn’t exist. The dynamics were different. And agents were luxuries.

Now sports dollars are so big, the contracts so complicated, agents have become necessities. “Dealing with the type of money we’re dealing with today, you definitely need one,” says Upshaw, who never had an agent during his playing days. Today, in fact, most general managers would rather negotiate with an agent than a player. Athletes who represent themselves get emotionally involved in the process, which can be disruptive for all concerned. It’s not the best thing for a player’s ego to hear he’s not the best at his position anymore or that the team doesn’t need him anymore.

“I have not dealt with a player in 25 years and I’m grateful,” Williams says. “They wouldn’t know what to do. You couldn’t get a deal done. They’ve got to have a rep. And after a player signs, they need someone to help with taxes and finances. That’s very important. If their finances are messed up, their head is messed up. If the player has someone taking care of that, it’s a plus.”

In the early 1960s Los Angeles Dodgers pitchers Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale decided to negotiate as a team, demanding $120,000 each under the direction of agent Bill Hayes. They want comparable pay, which the Dodgers didn’t like. Drysdale was great, but Koufax was greater, and the greater attraction; he was the one who put asses in the stands. In the end, Koufax got more than Drysdale, but they both earned more than Los Angeles would have paid otherwise.

Hayes was the first agent taken seriously by baseball. “It was the first union in baseball, but it was only two players,” says Andy Zimbalist, Smith College economist and author of Baseball and Billions.

Koufax and Drysdale’s strategy worked well for their day, but imagine them, or Mantle, Mays, Ruth, Tittle, Cousy, Russell or Howe with proper representation under modern free agency. Those guys were little more than chattel under the old system and were paid as such. They were owned in perpetuity by their teams. Fans today complain about players hop scotching from team to team, lacking franchise loyalty, but barely two generations ago, athletes had little to no control over their career destinies. If they played the game, they danced the owners’ tune.

Why do players make so much money now?

“The agents facilitated it but you have to give a lot of credit to the player associations,” says St. Petersburg, Fl.-based agent Jim Neader. “Before them, the owners had the leverage. They could pay you or not pay you. It’s like the Ralph Kiner thing. He hit 50 home runs and the Pirates wanted him to take a pay cut because they could finish last with or without him.”

Order ‘Ahead of the Game: The Pat Williams Story’ by Pat Williams with Jim Denney, available in print or e-book from Amazon.com by clicking on the book cover above! Mr. Media Interviews

Free agency has meant the gradual control of player destinies shifting from teams to the athletes themselves. And that, in turn, has increased competition for their services, creating opportunities for the agents to answer the question: How high is up?

“We wondered how high was up when we heard of the first $1 million contracts,” says CBS-TV college basketball analyst Billy Packer. “Now there are $20 million contracts. Now we have a rookie in the NBA signing for $70 million.”

Television dollars pushed those figures into the stratosphere. NFL teams, for example, jumped from earning $2 million annually, each, on national TV contracts, to $19 million each in 1989 and $40 million each in 1993, according to Steinberg. “That’s an expansion of 20 times in 20 years,” he says. “The percentage of the gross dollars in football that the players get – in 1982, it was 55 percent. To trigger the salary cap this year, the figure was 67 percent. That changes the whole face of what goes on.”

Agents negotiate bigger and better deals, taking approximately 5 percent off the top for their trouble. They also safeguard their guys, insulating them from the negative posturing management sometimes takes. Oral agreements still happen; high-tech negotiations via telephone, fax, pager, modem and satellite are becoming rote. “We finished (Dallas Cowboys QB) Troy Aikman’s first negotiation with Jerry Jones over a big-screen television set with them on a link-up in Dallas,” Steinberg says.

Many factors influence the success of an agent in getting the highest salary, signing bonus and incentives for a client. Two of the most significant are the unions’ relatively recent ability to disclose player salaries and the creeping impact of salary caps.

Salary caps changed the game just as things starting getting out of hand. Instead of simply seeking the separation of the owner from his wallet, players are finding themselves competing with teammates for a finite piece of a juicy pie. To sign a new impact player, general managers are asking current players for givebacks and concessions so as not to exceed the cap. They pose this question: Do you want to win or just get rich? In the ultra-competitive world of sports, there can be only one answer. It may not be what the players union had in mind, but it’s definitely happening.

“The cap is an artificial formula. It’s just a way of valuing contracts,” Steinberg says. “I put three ‘disappearing years’ in Drew Bledsoe’s contract. He signed a 6-year contract and got a $4.5 million bonus to sign. The Patriots only had so much room under the cap. In order for Drew to get $4.5 million, we need enough years for the ‘vision’ of it to be $7 million. If, at the end of three years, he’s played 50 percent of the plays, the last three years go away. We used the salary cap to give him the advantage of a huge bonus plus the advantage of getting out of his contract early. That’s because bonuses count differently against the salary cap than salary does. Under the cap, he gets $750,000 a year.”

Confused? Get in line.

“I don’t think a lot of people understand the caps,” Pat Williams says. “We spend a lot of time on education, explaining what can and can’t be done.”

o o o

Pat Williams has negotiated contracts with two of the NBA’s biggest stars, Shaquille O’Neal (Orlando Magic) and Julius “Dr. J” Erving (Philadelphia 76ers). The situations – and the agents – were generations apart.

Dr. J’s agent, Irwin Weiner, a colorful, flamboyant, archetypal agent thrived in the old smoke-filled rooms of yore. And when the 76ers acquired Erving from the New Jersey Nets, Weiner had his tiger by the tail.

“We bought Julius from the Nets for $3 million,” Williams recalls. “Part of the deal was that we had to get him signed.

“The numbers were huge,” he says. “That was the biggest deal cut to that point: $3 million to buy him, $3 million to sign him, $500,000 a year for six years. It was unprecedented.”

Fitz Eugene Dixon, Jr. had just purchased the 76ers and was not yet well versed in the sport, according to Williams, then the team’s general manager. Here’s the conversation they had about Dr. J:

WILLIAMS: “Fitz, Julius Erving is available.”

DIXON: “Who’s he?”

“He’s the Babe Ruth of baseball.”

“How much will it cost to get him?”

“Six million dollars.”

“Pat, are you recommending this deal?”

Williams gulped hard.

“Yes sir, I am.”

“Then go get it done.”

Fast-forward to 1992. The Orlando Magic won first pick in the draft and opted for Louisiana State University center The Shaq, clearly the man of the moment, a player who could transform the expansion franchise into a playoff contender.

“We knew it was going to be a tough signing. And it was,” Williams says. “Fortunately, his people were perceptive to know of our cap situation. But that was a very tough, intense signing.”

Leonard Armato represented Shaq. It was the first time he ever did business with Williams, but not the last. A year later, when the Magic miraculously won the top pick for the second consecutive year and chose Anfernee “Penny” Hardaway, he was represented by Armato.

o o o

Over a 16-year NFL career spanning three careers, Gene Upshaw’s timing always seemed slightly off. He was drafted in 1967 (first round, 16th overall), just after the merger of the NFL and the old AFL. There was no competition left for his services following the draft; he could either take the Oakland Raiders offer or leave it.

Order ‘Why Men Watch Football: A Report from the Couch’ by Bob Andelman, available in e-book from Amazon.com by clicking on the book cover above!

“Then, the year the WFL came along, I was already under contract,” he says. “And by the time the USFL came along, I was too old.”

But Upshaw, whose fame as a player has been eclipsed by his legendary stubbornness and success as executive director of the NFL Players Association, isn’t really griping about his compensation as a player. Upshaw felt that for the time, Raiders owner Al Davis treated him and his teammates fairly.

“I would negotiate my contract and Art Shell’s contract at the same time. I always figured whatever I was making, he should make,” Upshaw says. “Al Davis never let you get to the end of a contract anyway. He’d always bring you in and pay you more money. He believed in seniority. When I got there, nobody was going to make more money than Jim Otto. Later, no one made more money than me and Shell. And if Davis drafted somebody he had to pay more money to, he’d bring us up.”

When the opportunity to sign Ted Hendricks presented itself, Davis went to his players and warned that landing Hendricks would upset the team’s salary scale. “If that will improve the team, go ahead,” the players told the owner.

Another mark of how things change: Davis would only negotiate a player’s base salary. Upshaw says the man didn’t believe in incentive clauses.

“He said, ‘I expect you to do well. I expect you to go to the Pro Bowl. That’s what I’m paying you for,'” Upshaw recalls.

END, PART ONE

Part Two: War Stories

No two sports agents have exactly the same relationship with their clients. Some do straight contract negotiations and nothing more. Some handle client investments, everything from stocks, bonds and insurance to opening eponymous restaurants and sports bars. Some develop endorsement deals and give ongoing career advice. And some become more like family.

“Sitting with Troy Aikman the night of the San Francisco playoff game, when he’s been knocked senseless and doesn’t know where he is, doesn’t fit in any of these categories,” says Berkeley, Ca.-based agent Leigh Steinberg.

Another Steinberg QB snapshot from the 1993-94 NFL season: Jeff George’s tempestuous holdout from the Indianapolis Colts.

“Publicly, I had to defend my client,” Steinberg says. “Privately, I don’t ever think that sitting out a contract that’s already been negotiated is ever a good decision in a short career. In conflict resolution, my least favorite decision is having a player sit out of camp. When Jeff didn’t report to camp, the team said, ‘We don’t know where he is.’ That created a Howard Hughes flakiness that wasn’t there. Jeff was in the midst of a 6-year contract, of which he played three years. But it wasn’t about redoing the contract. He wanted to be traded.”

George eventually reported, enjoyed a fair season, and was traded to the Falcons in the post-season.

St. Petersburg, Fl.-based agent Jim Neader also provides a very personal service with no secretaries, no associates, no gophers. “I’m involved in every facet – management, taxes, travel,” he explains. “If the air conditioning unit goes out in my guy’s condo, I make sure it gets fixed. I prefer doing it all myself. I think it’s good for the clients; they only work with one guy.”

When Neader’s most high profile clients, New York Mets pitcher Dwight Gooden and his nephew, Florida Marlins right fielder Gary Sheffield, scrapped with the law, or during Gooden’s drug treatment, Neader was on the scene, acting as spokesman, protecting his clients’ interests. Damage control is a never-ending job with multi-million-dollar performance and endorsement deals flapping in the breeze. “Everybody has to deal with adversity. Their problems appeared to be worse than they were,” Neader says. “Gary’s weren’t that bad. And Dwight – he’s really an exemplary citizen now.”

o o o

In 1983, the average NFL salary was $100,000. In 1993, it was $750,000. Those numbers draw a lot of wannabes to the agenting business. But it’s very hard making a full-time living as a football agent. Expenses for newcomers are exorbitant; the odds of wooing and winning the rare athlete who will make a roster and survive the minimum three years it takes an agent to turn a profit, remote. It’s a good sideline though, for attorneys, accountants and professional managers, and it’s exciting for anyone lucky enough to score even one pro client.

Agent fees, however, are dropping. The reasons are simple: first, the players unions demand it; and second, competition for players is fierce.

“We urge players to negotiate commissions,” says Michael Duberstein, director of research for the NFL Players Association. “The problem is that they’re recruited by agents. They’re in the mode – recruited by high schools, by colleges – they don’t realize sports after college is a business. They think it’s a privilege to be recruited.”

Unscrupulous agents once pulled up to 12 percent from unwary athletes. In the 1980s, the top rate in the NFL was down to 5 percent; it’s now creeping to an average of 4 percent according to Duberstein and others.

“In basketball,” says Gary Woolf, president of Bob Woolf Associates, “there’s a maximum of 4 percent, and that’s going down. Players are being represented for 2 or 3 percent. There’s a downward spiral. But the money is greater, so there’s a good reason for that.”

“The vast bulk of players just won’t want to spend that 5 percent anymore,” says Andy Zimbalist, Smith College economist and author of Baseball and Billions. “There will be people who will be able to crack the major league level by offer 2 and 3 percent fees. The area of agency is ripe for a lot of competition.”

o o o

The agents whose names every sports fan knows – Steinberg, Neader and David Falk (Michael Jordan) – don’t hang around the schools any more looking for the next phenom. But that doesn’t stop the top talent from finding them: Steinberg alone represented four of the NFL’s No. 1 draft picks from 1989-93 (Aikman, Jeff George, Russell Maryland and Bledsoe).

When the annual college drafts roll around, it’s not just the student-athlete and his father in the hunt for representation. He’s helped by uncles, coaches, lawyers and alumni. “You’re not just meeting Drew Bledsoe,” Steinberg says. “He had a screening process with Oklahoma lawyers who grilled us for hours.”

One of Steinberg’s latest clients, Ohio State defensive lineman Dan Wilkinson, knew enough about the agent process before the draft to call several lawyers and make “who’s who” inquiries with the NFL Players Association – “things that were not the norm when I began,” Steinberg says.

Michael Duberstein’s NFLPA research department takes responsibility for certifying and regulating 800 player agents (only 300 of whom actually have active clients) and reading every NFL contract. His department also meets with college players each year, preparing them for representation by professional agents. He says today’s agents are generally consistent in the quality of work they provide, in part because of the association’s guidelines:

o Agents must be certified to represent NFL players

o Agents must have a college degree or equivalent work experience

o Agents must have a working knowledge of the NFL collective bargaining agreement

o Agents must use a standard contract, provided by the NFLPA, to form agreements with players

“I wish certification were stricter,” Gary Woolf says. “We need a high level of ethics and code. If they can’t meet that, they don’t belong in the industry.”

Agents don’t have to be lawyers – although many are – because the various players unions and/or management typically use standard employment contracts. No agent writes an NFL contract; the league uses the same contract for every player. The agent fills in the annual salary and incentives. Even incentives have been standardized.

“The role of the college player should fall in two areas: finish school and make a pro roster,” Duberstein says. “The agents’ job is to get a contract.”

“We start the process at the combine,” says NFL Players Association Executive Director Gene Upshaw. “From that point on, cradle to grave, we try to help the players any way we can.”

Duberstein stresses that a kid just out of school must be comfortable with his agent and trust his judgment implicitly. Because if a negotiation with a team begins to sour, the team will inevitably try an end run around the agent, warning the family that if their collegiate all-star doesn’t accept the team’s latest offer, he’ll be pumping gas come opening day.

o o o

Some men become athletes. Some know, by their teens, that dream won’t become real, so they turn their love of sports into coaching, management, broadcasting, sports writing – and agenting. The latter may be the least profitable path. Start-up expenses mount and only a small percentage of blue-chippers make it into the pros. For the agents on top of the pyramid, however, it’s champagne and caviar.

Leigh Steinberg celebrated his 20th NFL draft as an agent in 1994. He met his first client, first-round, No. 1 draft pick Steve Bartkowski, as an undergraduate dorm counselor while in law school. The timing couldn’t be better; the nascent World Football League was competing with the NFL, running up salaries for the first time in years.

“We got lucky and Bart got the largest rookie contract in NFL history,” Steinberg says. “It eclipsed Namath and Simpson, $400,000 for six years. His bonus was $250,000. His salary was $40,000.”

o o o

Jim Neader became an agent when his pro hockey career crashed the boards during Minnesota North Stars pre-season camp in 1978. The Stars were staying in the same hotel as the Minnesota Vikings. Of the football players Neader met, he struck up a particularly good rapport with Paul Harris. Neader, holder of a masters degree in business, was already thinking about a new career.

“I could see I wasn’t going to make it,” Neader recalls. “I told (Harris), ‘If I get cut and you need an agent . . . ‘ Three weeks later, he got cut. He hired me and we got him on an NFL team, the Bucs.”

Neader’s stable grew slowly, focusing on football and baseball players close to his home in the Tampa Bay area. His second client was Guy Hoffman, a one-time pitcher for the Chicago White Sox and a Bradley University fraternity brother of Neader’s. Next came Lloyd Moseby, the Toronto Blue Jays No. 1 draft pick in 1978, followed by Neader’s most notable and notorious client, New York Mets ace Dwight Gooden.

“I followed his career at Hillsborough High School,” Neader says. “I didn’t say a word to him until his senior high school season was over. Then I met with him and his dad.” Gooden signed on with Neader in time for the June 1982 draft and they’ve been together ever since. “I believe in him and he believes in me,” Neader says.

Neader hasn’t hung around the schools in more than eight years and he’s very selective about taking on new clients. He almost took on a new football player a few years ago, but the feeding frenzy of would-be agents/sharks ended that deal before it happened.

“There was a prospect my brother knew from high school. Good player, small town setting. I heard the guy was a potential draft pick. My brother talked to him, said, ‘After the season, talk to Jim.’ The season ends and my brother schedules a meeting. The week of the meeting, the guy cancels. He was deluged. Eighty inquiries, 20 visits. Some major agents, from all around the country. Five years ago, it would have been different for him. I don’t think the outcome would have changed. I never met the guy; he never got drafted. Signed a free agent contract; never played in the NFL.”

o o o

The late Bob Woolf may well have been the most successful, best-known and beloved sports agent of all time. His sports clients included Larry Bird, Carl Yastrzemski, Joe Montana, Julius Erving and Vinny Testaverde; his entertainment clients included Larry King, Gene Shalit and New Kids on the Block. He negotiated big deals with Donald Trump, Ted Turner, Roone Arledge and Red Auerbach. He even wrote a well-received book on negotiating, Friendly Persuasion (Berkeley).

Woolf’s first client was former Boston Red Sox pitcher Earl Wilson. Wilson wasn’t allowed to bring anyone else into his negotiating sessions, however – not his wife, not his best friend, and certainly not Woolf. If he had a question, he had to excuse himself from the table, walk down the hall and call Woolf from a pay phone.

Times have certainly changed. And while Woolf is gone, his Boston sports management firm, Bob Woolf Associates, continues under the aegis of his son, Gary, 28. Although Gary did his first professional contract more than a decade ago while an undergraduate at Harvard and was perhaps the youngest agent in sports at the time, he hasn’t exactly followed in dad’s footsteps. He’s a behind-the-scenes player at the firm, which also employs his mother and sisters.

“With the passing of my father, people wondered which direction the company would go,” Woolf says. “But we had already been planning a new direction because my father had been planning to step back. In some ways we’ve become a better company. When my father was here, he was the most important person in the company. We don’t have another Bob Woolf. Now we have other agent who have stepped up, agents who are maturing into bigger roles.”

Woolf says representation can be very gratifying.

“In two or three years, a young athlete will make decisions affecting the rest of his life,” he says. “We’re involved in guiding them through every aspect of their career. We’re a main resource for all the life decisions they make. It’s a tremendous opportunity to influence people’s lives and guide them through a rocky transition.”

Imagine these kids coming out of college, many of whom have never touched wealth of any kind, kids whose lives have always been directed by parents, guidance counselors and coach, and who are suddenly transported a thousand miles from home and given a million bucks. They look to agents for help and direction.

Their careers may take off, but when they are injured, when they’re in the hospital, when they go through operations and rehab, agents live through all that with them, according to Randy Vataha, the agent responsible for football at Bob Woolf Associates. “It’s all part of their career, what they look to you for help,” he says. “You have to pump them up.”

Through his father’s eyes, Woolf saw professional athletes rise from modest salaries in the 1960s through the promise of free agency, new leagues and rising salaries in the ’70s. The ’80s brought the specter of salary caps and personal services contracts. And as that decade gave way to this one, athletes gained greater economic savvy and control, first in basketball, then football, and now in baseball.

“The players can appreciate much more for their work,” Woolf says. “Both sides are partners. Management is still making money and the players are also doing well.”

Woolf thinks the trend worth watching in representation involves corporations such as Nike, which now represents athletes in addition to using them for product endorsement purposes. “There’s a lot of integration occurring,” he says. “Corporations are integrating with the agency process, handling the players’ careers. The role of the agent is at an impasse because the players associations are so strong. There’s a tug-o-war. Who represents the client? Is it the players association or the representative?”

o o o

Contract negotiating during the early phases of the sports agent/free agency era wasn’t too complicated other than keeping track of the zeroes. In the old days, the player or his agent said, “I want this,” and the team said, “You can’t have it.”

“Negotiating is a lot of fun. It’s a challenge,” Randy Vataha says. “You don’t just go in and say, ‘My player wants a million,’ management offers $500,000 and you settle at $750,000. There’s all kinds of issues in terms of timing so the contract expires at the best time. Issues to be considered include when collective bargaining expires and when something new might come up. One player went from $450,000 to $2.4 million in one year because we got him in the last year before there was a salary cap.”

Computer runs, in-depth statistics and analysis are the agent’s stock in trade when they face off with management.

Half the ammunition agents use comes from salary comparisons within the athlete’s league. That information is typically provided by the players unions. The NFLPA, for example, began supplying salary data to agents in 1983, in exchange for the agents funneling their latest deals back to the union.

“Until the beginning of 1982, no player in the NFL had any idea what any other player was making,” Michael Duberstein says. “Nor did any agent know what salary trends were or did they have a glimpse at comprehensive salaries.”

Duberstein says that in football, once adequate salary reporting was available on both sides of the negotiating table, salaries accelerated and inequities in player compensation from team to team were eliminated.

“The role of the agent can be two-fold,” Duberstein says. “There can be a very passive role, essentially saying, ‘No, no, no – yes!’ knowing when to say yes. Or they can be a proactive agent, taking that information and coming up with creative ways to bend rules and get a contract.”

The other half of a negotiator’s ammo comes from the ingenious compilation of a player’s on-the-field stats.

“We have a research staff who are given a simple task: go find any statistical pattern that presents our players in a positive light,” Steinberg says. “Their job is to produce the most amazing statistical categories possible to buttress our salary demands.”

Steinberg’s staff produced this gem during a salary arbitration: Wade Wilson was the first quarterback in history to throw 6-plus yards per attempt and make the Pro Bowl in the same season. “That’s a not a statistic published in The Sporting News,” Steinberg says, chuckling.

There are other ways Steinberg uses stats. In negotiating Drew Bledsoe’s deal, he started with the assumption there is always a premium paid the first quarterback picked in the annual college draft, and an even bigger premium when the first player picked overall is a quarterback. Next, he pointed to the impact another client, Troy Aikman, had just had in winning the Super Bowl for Dallas.

For client Thurman Thomas, the Buffalo Bills star running back, he provides analysis of what happens every time Thomas touches the ball, how he consistently makes things happen.

“We put together statistics, bar graphs and colors that jump off the page,” Steinberg says. “At times we’ll make a compelling audio/visual presentation. We can also anticipate the arguments a team will make and refute them. Of course, the methodology has to be sound or the results can be questioned.”

o o o

For all his success in negotiating some of the biggest deals in sports, Leigh Steinberg is worried about the future of his men and the games they play.

Athletes, he says, must understand the fleeting nature of their careers and build other skills toward the day they can no longer throw a long bomb or hit a ball out of the park. “The big mistake for an agent is to simply classify a player as a function of his bank book,” Steinberg says. “The only certainty I have, in every athlete I represent, is that at a young age, he is going to have to transition into another line of work.”

As for fans, he says agents must be reminded that sports is fantasy.

“Sports exist as an entertainment industry,” Steinberg says. “It’s not like putting bread on the table. It’s a discretionary expenditure. To the degree we keep feeding fans stories of free agent salaries, we’re destroying the games. Agents have a responsibility to keep the games affordable.”

END, PART TWO

Part Three: Power Players

Read the sports headlines lately? The scores have been superseded in importance by salaries and free agency. Everyone’s getting rich except the guys footing the bill – the fans.

But read past the headlines. For every college player signing a first pro contract for $70 million, there’s a veteran quietly accepting an equally huge reduction in pay. It’s the first sign of reality hitting the sports salary spiral, indicating there is a ceiling on how high all this madness can go.

Whereas free agency at first seemed a license to steal for athletes and their agents, there’s obviously a price. What increases the fans don’t bear, the players apparently will.

Don’t believe it? Well, if someone who still makes hundreds of thousands of dollars but must accept deep, deep pay cuts can be described as a victim, that’s what the system has turned pitchers Jack Morris and Bobby Thigpen and quarterback Mark Rypien into.

Morris swallowed hard and watched his base salary slip from a career-high $5,425,000 in 1993 to $350,000 in 1994. Thigpen dropped from $3,416,667 to $200,000. At least they found jobs; Rypien was cast adrift after refusing a new contract that would have cut his pay by more than two-thirds, from $3 million in ’93 to $1 million this fall.

This is the side of contract negotiations no agent wants publicity for. It’s a bold slap of reality following years of player successes in gaining ever increasing free agency and a bigger piece of the revenue pie. Agents who spent the 1980s and early ’90s squealing, “Gimmee, gimmee, gimmee!!” without regard for the impact such wanton greed now have some serious explaining to do. Ditto for their unions, and, for that matter, the teams who eagerly made dollar commitments for today without considering the reverberations tomorrow.

All across pro sports, unproven rookies get the keys to the bank and yesterday’s stars are being unceremoniously shown the door. Athletes are being split into three camps: the haves and have-nots are being joined by the hads.

Many NFL stars fell into a black hole unintentionally created by their union’s last collective bargaining agreement (CBA) with the league. In an effort to gain greater free agency for players and yet avoid total anarchy, the union compromised with management. In exchange for allowing veteran players with more than five years experience and whose contracts expired beginning in 1993 to become free agents (four years experience as of ’94), the NFLPA agreed that teams could designate “franchise” players who were pre-empted from free agency as long as they were paid accordingly. “Accordingly” meant at least matching the average salary of the top 5 players at the franchise player’s position. The “franchise” tag sticks with the player until their contract expires or they retire. Then the team can tag a new player.

A second layer of top athletes, labeled “transition” players, were created as a bridge between the old system and total free agency. Teams were allowed two “transition” players by guaranteeing them the average salary of the top 10 players at their position.

Players and their agents had no say in accepting or declining the “franchise” or “transition” tag. And once the two transition players’ relationship with their current team ends, the teams don’t get replacements. According to the NFL Players Association (NFLPA), about half the NFL’s franchises designated transition players.

It sounds like an equitable system, but agents say it didn’t work. Most rue the day the terms “franchise” and “transition” were adopted.

First of all, the salary numbers were based on the preceding season’s totals, not the current negotiating season. And while other teams could bid on franchise and transition players, the athlete’s current team retain first right of refusal, meaning if it matched an offer, the player stayed put. Finally, teams were given great latitude with franchise or transition players. While player contracts expire annually on February 28, teams knew what it would cost to keep their designated stars months earlier.

“It worked to the detriment of all the transition players,” says Edward Sewell, president of the San-Francisco-based Professional Sports Center. “Having the transition title meant that none of those players – the best in the NFL – ever got any job trips or offers from other teams because the system, or the fraternity, said, ‘You don’t mess with my transition players and I won’t mess with yours.'”

Collusion?

“You use that word,” Sewell says. “I call it a gentlemen’s agreement. You have to prove collusion. It’s a strong word.”

“Any agent who believes that, we have the strongest anti-collusion language of any sport,” counters Michael Duberstein, NFLPA director or research, citing Article 28 of the collective bargaining agreement. “All they have to do is come to us and we will take action. Not one agent has come forward to say the clubs are colluding.”

Sewell hit the transition situation with two different clients: Ricky Reynolds in 1994 and Ronnie Harmon in 1993. A third client, Cris Dishman, was listed by the Houston Oilers as a franchise player. But because of management fraternity, Sewell says, the trio received little or no outside interest.

“Their teams took that to mean, ‘Oh, gee, you’re not that valuable to anybody but us. Therefore, we’re not going to pay you market value, we’re going to pay you whatever the minimum is at your position,” according to Sewell. “Plus they are able to keep these guys out of the marketplace, away from other teams, while they scratch their heads and decide whether they really want to sign him. So they got the best of every world. They lock their best talent in, kept ’em away from the marketplace and they were able to rescind the offer at any time. As long as the title stays with you, odds are you’re going to stay with that team because you don’t get offers to move.

“In Ricky Reynolds’ case,” Sewell says, “the Bucs kept him out of the marketplace starting in February when there were some choice jobs available. There was one in Seattle that Nate Odoms got. Ricky had plane tickets to Seattle but the Seahawks decided they would do the Odoms situation because it didn’t require any kind of match. In other words, when they negotiated the deal with Nate, they had Nate Odoms. Versus negotiating with Ricky Reynolds and waiting a week to see if the Bucs were going to match it. In that week, they would have lost Nate.”

By the time Tampa Bay lifted the transition tag from Reynolds and freed him to negotiate, Sewell says, all the available jobs at Reynolds’ position had vanished and his salary was in freefall. Whereas his transition value was $1.7 million, Sewell’s first offer for his client was a mere $750,000. Fortunately for Reynolds, Ray Perkins, the former Bucs coach who drafted him, had moved on to the rebuilding New England Patriots and still believed in his skills. Perkins persuaded his boss, Bill Parcells, to take a chance on Reynolds, who signed a deal worth in excess of $5 million for three years, including $2.23 million for ’94.

“We went from Diet Pepsi to Dom Perignon,” Sewell says.

Reynolds, of course, did better than his former teammate and co-holder of the Bucs transitional tag, Reggie Cobb. Cobb was entitled to a $2.6 million salary until the Bucs yanked his tag. Forced into the open market, the best he could do was $1.1 million with Green Bay.

“Helluva drop,” Sewell says. “Never get that back.”

Michael Duberstein doesn’t think agents such as Sewell understand the transition label.

“Transition players were imposed in the settlement by the league,” he says. “What they wanted was to protect some of their better players. They would not make a deal, there would be no CBA, without the ‘transition’ and ‘franchise’ system. It was because the owners were so scared they were going to lose all their best players. No one here proposed it or wanted it. The goal of the Players Association has always been total free agency when the player’s contract ended.

“Did it work out the way we anticipated? Most of the clubs didn’t use it. The reason is, they don’t want to guarantee that much money. By the time we hit ’95, very few clubs will be able to designate transition players, anyway,” Duberstein says.

Duberstein thinks the real problem agents have with the transition and franchise tags is it makes agents virtually unnecessary to players.

“I don’t see anything rational about an agent saying “transition” and “franchise” doesn’t work. All it did was guarantee them free money,” he says. “If I was a transition or franchise player who accepted a contract, I wouldn’t give an agent a penny. He didn’t do anything.”

The NFLPA encourages its members to pay their agents. But for transition and franchise players who accept a salary – without negotiation – equal to the top 5 or top 10 players at their position, Duberstein thinks there might be a case for withholding a commission. “In a situation where there was no negotiating, I don’t know what the (union’s) ruling would be,” he says.

The CBA has its positive points, particularly that so many players gained free agency when their current contracts expired. But labor and management wind up trading big salaries for loyalty. That’s a two-way street, however. The players are loyal to whomever pays them the biggest salary. And when a player’s salary gets out of whack with his or the team’s performance, the team’s loyalty to him ends.

“What big salary gets you is loyalty to yourself,” Sewell says. “It pushes you into a selfish mode. Unfortunate, isn’t it? The days that a fellow would always be identified with one team are over.”

Another creation of the latest NFL collective bargaining agreement was the league’s first salary cap.

Ken Staninger, president of the Montana-based Staninger Sports Agency, represents former Washington Redskins quarterback and Super Bowl XXVI MVP Mark Rypien. Rypien found himself on the wrong side of the salary cap this year. Although Rypien, who had taken his team to the playoff in four of six years, wasn’t burdened with either the franchise or transition tag, his agent’s negotiating hand was damaged by several factors. Rypien endured an injury-plagued ’93 season and, when he did play, he didn’t play well. The Redskins had a lousy season overall (4-12), eventually hiring a new head coach, Norv Turner. And the former Super Bowl champs were stocked with aging, over-paid players who tied up resources.

“It was a horrendous situation” for Rypien, Staninger says.

Earning a high draft pick and a shot at either Tennessee QB Heath Shuler or Fresno State QB Trent Dilfer, Rypien became expendable and that’s the way the Redskins handled him. The team offer its former star a 1994 salary offer of two-thirds less than he made in 1993 – and that was their second offer. It lacked any incentives whatsoever, according to Staninger. Rypien declined it and was released. But by then, as in Reynolds’ situation, every other team in the league had settled its starting quarterback position, leaving Rypien high and dry.

“What the Redskins did was a calculated move,” Staninger says. “They had Mark under contract. On February 1 they got a new coaching staff. At that time they were not sure they could draft the quarterback they liked. Then they decided they could. They kept Mark to the last possible date. Mark thought the cut they were asking him to take was unreasonable, that it was time for a complete change. The biggest reason we turned the Redskins down was they would not consider any incentives. We took that to mean we weren’t wanted.”

Staninger and Rypien’s frustration is the flipside of the good timing you hear so much about. Their timing couldn’t have been much better when Staninger insisted on a one-year contract in 1991 and Rypien subsequently took the team to the Super Bowl. “At the time, we were rewarded,” Staninger says. “Now, with Mark coming off his worst year, the timing couldn’t be worse.”

Again, the NFLPA’s Michael Duberstein thinks this is a case of an agent who just doesn’t get it.

“Players who used to get released after camp, just before the season started, and would have to scramble are now getting released in spring,” he says. “Now they have more time to find a place to play. . . The fact players are being asked to take less money is not unique to the salary cap.”

Maybe Rypien just became another overpaid superstar caught in the back-end vortex of outrageous salaries banging head-first into a salary cap. Before there was a salary cap, nobody worried about coming out the other side.

“Now I think some of these big deals are going to turn into nightmares,” Staninger says. “There are few guaranteed contracts. Next year, you’re going to see even more big players who will be released or asked to take huge cuts. The teams, the GMs, don’t like it any more than we do. But their hands are tied. This is not a unique year. You’re going to see it every year.”

+ + + +

Not everyone thinks there’s anything new or particularly worrisome in the expansive disparity between the multi-millionaires on a team and the rest of the guys putting on their uniforms one leg at a time. Don Fehr, executive director of the Major League Baseball Players Association, thinks it’s just a matter of separating the regulars from the utility players.

“That’s always been true,” he says.

Salary caps just exacerbate the differences, says the only man who stands between baseball players and the sport’s inevitable push toward a cap. “The biggest problem with a salary cap from a fan’s point-of-view is it inhibits your ability to improve the team. And everybody knows the way to improve a business is to make better investments ahead of time. That’s why basketball (which has a cap) doesn’t have anything like baseball’s balance. The big market teams always win and the salary cap multiplies their advantage.”

Fehr doesn’t see any harm in letting the free market determine player salaries from here to eternity. And pointing out baseball set an all-time attendance record in 1993, he doesn’t interpret that as fans complaining.

“It’s great gossip and people like to pontificate on it,” he says. “But I don’t think (salaries) affect customers.”

H. Irving Grousbeck agrees with Fehr on this point. Now a lecturer in management at Stanford Business School, Grousbeck made a lot of money in cable television and in 1992 toyed with purchasing the San Francisco Giants. But he backed away after studying the team’s books, salary and revenue prospects.

“It’s a very revenue-driven business,” Grousbeck says. “The Houston Astros had a $14 million payroll two years ago; one club today has a $50 million payroll. Some of the teams with $37 million payrolls are making money; some with $29 million payrolls are losing money.

“As a would-be owner,” he continues, “I hate to see the balance of power go to the players. And I hate to see the players grouse, but I don’t think it’s the death-knell for baseball. Am I concerned about player salaries? Not if I’m the Yankees. Not if I’m the Toronto Blue Jays. But the Giants are going to lose money this year because they play in Candlestick. If they played in St. Petersburg or Cleveland, they’d make a lot of money.”

But Grousbeck, a huge fan of the game, doesn’t think fans are being turned off by seeing star players become jillionaires. Would they rather hear less about it? “Sure,” he says. “Does it keeps fans from the ballpark? I don’t think so.”

Money is a part of sports these days. Apparently it’s not a serious depressant. If it were, it would dampen attendance everywhere. And there are plenty of places attendance is up, not down.

+ + + +

Salary inflation hasn’t yet hit the NHL as hard as it has other leagues, but it’s coming, if increased attendance, wildly successful expansion franchises and rising ESPN television ratings are any indication.

“It has been moving up,” says Greg Jamison, chief operating officer of the expansion San Jose Sharks, a team which reached the playoffs in only its third season. “Higher salaries have been paid out in the last two or three seasons.”

All of his players are represented by agents and Jamison thinks that’s for the best.

“I think agents are just one of the players in sports,” he says. “They’re a part of our business, just as players, owners and domed stadiums are. It all works together. I don’t blame agents for where sports is today. There are good agents and bad agents, just as there is good management and bad management. We’re all players and have to take equal responsibility. And equal blame, maybe.”

Jamison hopes hockey can learn from the salary cap stumbles of the NBA and NFL as it moves toward locking up a similar vehicle with its players union. “I think the successful leagues and teams have to work together,” he says. “The players are who people come to see skate and play to the best of their ability. But management, owners and athletes have to be on the same page. There has to be a common goal.”

The NBA cap works for Jamison, but as a football fan, he’s worried about the impact the new NFL cap will have on the San Francisco 49ers. “We’ve heard a lot about the 49ers having to let people go to stay under the cap,” he says, nervously. “Cap management is building stock in your team and being prepared for the future. Sometimes there’s player movement that’s not fully understood (at the time). Why is a player who is popular suddenly moved? Maybe he came out and said, ‘I’m not re-signing with the club.’ Maybe to retain value, they moved the player. I have a lot of respect for GMs in all leagues who have to maintain a mix of veterans and youth and know when to make a move. It’s an art form.”

Where is it all going? There’s no easy answer.

“Where’s the airline industry going?” Jamison retorts. “Every industry has to ask itself that. When I was a kid, a pack of gum was a nickel. What’s the ceiling on gum? I’m not trying to be trite. These questions – sometimes, in a free market, things try to shake themselves out. We try to do long-term planning. We try to anticipate (cost) increases here, revenues there. The league has goals; individual teams have goals. The Sharks’ goals are simple: we want to win every game; we want to sell out every game. We want the best players. We want them happy. And we want the fans happy.”

+ + + +

“The biggest problem I have with agents is the number of holdouts,” says Peter Hayes, managing editor of College & Pro Football Newsweekly. “Guys in their rookie year miss camp, marquee players hold out till the middle of the season. Most of these guys want the best deal possible. They want security. Nobody can begrudge them that. But I think it’s the agents controlling the player, filling his head with nonsensical things. It’s bad for the game. Football isn’t alone in this. All sports is full of this nonsense.

“I think the average fan who supports a team has a hard time understanding,” Hayes says. “It all comes down to performance. Emmitt Smith performs and they still love him. If the players perform on the field, the fans don’t care if they’re making $10 million or 10 cents.”

Hayes blames agents for damaging young players by pushing them into professional drafts too soon, thereby sacrificing their education and full college eligibility. “These guys who come out early – many go late in the draft or they don’t make it at all,” he says. “Where did they get the idea to come out early? Agents.

“I think a lot of good players are getting a lot of bad advice,” Hayes says.

Soon, they may get their advice from a new source: sporting goods manufacturers. Nike hit the industry first, formalizing its informal relationships with Bo Jackson, Deion Sanders, Alonzo Mourning, Harold Miner and several other superstar athletes last summer into Nike Sports Management. Former CBA commissioner Terdema Ussery is president of the subsidiary.

“Our focus is to work with a select few Nike athletes on everything but their playing contracts,” says public relations director Keith Peters. “We work on everything in their portfolio, from business advice to finding other endorsements. It’s our charge to go out and market them.”

Mourning was represented in his last Charlotte Hornets contract negotiation by agent David Falk, who handles Michael Jordan. But instead of sticking with Falk for the rest of his business, he dribbled over to Nike. “He worked with David Falk on his Hornets contract, paid the going rate,” Peters says. “All the rest of his business and accounting, soup to nuts, is what we do for Alonzo.”

Traditional player reps are dismayed by Nike coveting their turf and predict the company will not get off the ground in its new venture. Too much potential conflict of interest, they say.

“Nike says they’re going into the business. I think that’s a grave mistake,” Ken Staninger says. “Nike may try to cherry-pick the superstars of the future. And it would make sense if Nike is successful that Reebok will follow suit. But if they’re out competing with us, we’re not going to be too excited talking about a Nike contract when we have a superstar. You don’t want to support a company competing with you. And you’re always going to be concerned about client interference.”

“To the degree that a lot of agents do more than just player contracts,” Peters says, “perhaps they feel they’re competing with us. But to date, we have not negotiated a player contract. There may be a misunderstanding about that.”

Nike gets a pretty good deal by avoiding player contracts. No worries about certification, no outside control over its fee schedules and its athletes are already household names. The company also doesn’t waste time and money chasing raw talent or developing it. “We’ve become aggressive in a selective way,” Peters says. “Each year we hope to get one or maybe two baseball, basketball or football players, the kind of athlete it makes sense for us to invest resources in and who has the potential to stand above the crowd and be attractive to other sponsors.”

Peters figures Nike Sports Management’s competition are the full-service sports agencies and agents: IMG, ProServ, Falk and Leigh Steinberg. And he knows Nike won’t be the last manufacturer to go this route. “I wouldn’t be surprised if some of (our competitors) were to do it,” he says.

Staninger doesn’t like it one bit.

“Nike is so big,” he says. “I don’t know why they’d want to get into this aspect of the business.”

+ + + +

What do fans think of all this? Many are pissed. They want their favorite teams well-stocked with top talent, but mostly they want a return of debate over RBIs, shots on goal and free throw percentages, not option years and incentive clauses.

“Most people hear salaries – three years, $5 million; two years, $8 million – we just can’t comprehend them,” says Ken Silverstein, a veteran sports radio talk show host who spent eight years with Houston’s KTRH before joining WFNS in Tampa Bay. “These numbers roll off our tongues like we’re talking about Monopoly money. We see it coming out of our pockets because we see prices going up – tickets, hot dogs, parking. Fans understand that; they don’t like it.”

Rising sports ticket prices in football, basketball and hockey are right on the cusp of forcing the middle class out for good. Instead of season tickets or partial season tickets, the average family of four might spring for one or two games a year as a special outing. “It’s pretty mind-boggling what it costs for a family of four – or two,” Silverstein says. “Sports has become a very white-collar thing. It’s not good, but that’s where it’s going.”

“I have very mixed feelings,” says Dan Gutman, lifelong baseball fan and author of several books including Baseball Babylon (Penguin) and It Ain’t Cheatin’ If You Don’t Get Caught (Penguin). “On one hand, utility second basemen hit .210 and get million-dollar salaries. That’s outlandish. On the other hand, the players were screwed by owners for 100 years. Now it’s their turn to get even.”

In general, Gutman finds the emphasis on salaries a bore.

“I don’t want to read about arbitration and how much this guy is going to get paid. It’s not what sports is all about,” he laments. “I speak to a lot of fans. The overwhelming feeling is that the high salaries have hurt the game. It puts players out of touch. They don’t dive for balls.”

Still, he says, baseball ticket prices haven’t exploded the way they have in other sports, so as long as Gutman can still get a $6 general admission seat at Veterans Stadium in Philadelphia, he’ll keep his gripes about Darren Daulton’s million-dollar deal to himself.

end