(AUTHOR’S NOTE: What follows is an excerpt from my very first book “STADIUM FOR RENT: Tampa Bay’s Quest For Major League Baseball,” which was originally published in May 1993 by McFarland & Company. An updated, expanded 2nd edition of the book was published in 2015 by Mr. Media Books. It is available in paperback or ebook wherever great books are sold. — Bob Andelman)

“I’m no rabid baseball fan. I’m an average guy, maybe not even average. I’m not going to sit there and talk to someone about so-and-so’s batting average. That’s not my game. I’m a businessman.” — H. Wayne Huizenga, Chairman of the Board, Blockbuster Video, Florida Marlins

The death in 1989 of Miami Dolphins owner Joe Robbie, the man who brought professional sports to Florida, might have dealt a crippling blow for baseball expansion in the southern part of the Sunshine State had it not been for the emergence of H. Wayne Huizenga.

The Making of a Blockbuster: How Wayne Huizenga Built a Sports and Entertainment Empire from Trash, Grit, and Videotape by Gail DeGeorge. Order now by clicking on the book cover above!

Huizenga was the embodiment of the American dream. A college dropout who dreamed large, he bought a garbage truck in Fort Lauderdale and formed his first company, Waste Management Inc. It became the largest garbage company in the world, of course; Huizenga didn’t do anything small.

He left the company in 1984 with 4-million shares of stock worth an estimated $150-million. In February 1987 he bought into a Texas video rental company with a handful of retail outlets and a fuzzy notion of becoming a nationwide chain of video superstores. Two months later he took over the company and fine-tuned the picture. Soon, Blockbuster Video became as synonymous with renting videos as McDonalds is with Big Macs.

Blockbuster caught on quickly, expanding across the United States by building new stores or buying competitors. Almost every day, a Blockbuster Video store opened somewhere. By mid-1992 there were 2,935 stores in operation and more coming on-line daily. Other chains competed on a regional basis, but none could match the Fort Lauderdale, Florida, chain’s name brand recognition coast-to-coast. In 1991, with Huizenga as its chairman of the board and chief executive officer, Blockbuster Video grossed $1.5-billion in sales. Entertainment Weekly abruptly ranked Huizenga the ninth most important person in the U.S. entertainment industry.

And Blockbuster was mighty in other ways. Early on, Blockbuster management made a decision to avoid X-rated and even some R-rated films. Its refusal to stock The Last Temptation of Christ in the mid-’80s made news and deflated the grosses for the film’s producers. The chain stressed family values and themes. A movie that wasn’t stocked on video by Blockbuster after its theatrical run wasn’t going to earn much money.

Anyone who earns blockbuster bucks — U.S. News & World Report estimated Huizenga’s net worth at $600-million in 1991 — is going to have a few dollars left over. But Huizenga isn’t a man to spend money freely. He spends money only to make more. That’s why Huizenga bought half of Joe Robbie Stadium (JRS) for $5-million (and assumed responsibility for half its debt) and a 15 percent interest in the Miami Dolphins for $12-million in March 1990.

“When I approached Joe Robbie about buying into the stadium — or buying the stadium, because at first I wanted to buy it — he showed me drawings and a model of the stadium,” Huizenga says. “That stadium was designed for baseball from day one. The only thing was, the retractable seats weren’t put in. I looked at the economics of bringing baseball to the stadium. You put another 81 events in the stadium, bring another two and a half million people in, all of a sudden that made the stadium investment look very attractive.”

He called his good friend Carl Barger, a member of the Blockbuster board of directors and, more important, president of the Pittsburgh Pirates.

“The more questions I asked, the more [buying into the stadium] looked like a good thing to do,” Huizenga says. “When I signed the agreement with the Robbies, there was about a three-month lag from the signing to the closing. [During that time] I got more and more interested in baseball. So when word got out that we were going to close the deal, not only did we say we’re going to buy part of the stadium but we’re going to go forward and try to get an expansion team.”

One of the first people Huizenga told about his baseball plans was Frank Morsani, the man who tried to bring a team to Tampa Bay.

“I met with him in Jacksonville before he ever made his bid,” Morsani says. “I know Wayne pretty well. People say well, he had this thing with Barger already done. I don’t know whether he did or not unless he is an awful good con artist. We were on the Florida Council of 100 together and we had a meeting in Jacksonville. He and I spent a couple of hours together talking about it. He said, ‘You deserve baseball. For all you have done … but I have to put in a bid. I am not going to go to anything elaborate. I am not even going to do anything, just tell them we are here.’ That’s exactly what the man told me. I was concerned but I didn’t think we could lose.”

Order ‘Stadium For Rent: Tampa Bay’s Quest for Major League Baseball’ by Bob Andelman, now available in an expanded, updated and illustrated 456-page special edition, available from Amazon.com by clicking on the book cover above!

Once he jumped in and formed South Florida Big League Baseball Inc., Huizenga entertained second and third thoughts about the cost. Every time another superstar ballplayer signed a multiyear, multimillion-dollar deal, Huizenga winced. For a man who ran his company by the bottom line, baseball’s salary structure looked insane.

“We hired [the accounting firm of] Arthur Andersen & Co., which had experience doing auditing for several different teams,” he says. “We ran the numbers and ran the budget. We looked at that and came to the conclusion that we wouldn’t be interested in baseball in any city but South Florida.”

Owning a sports franchise was not always a goal of Huizenga’s. A native of Evergreen Park, Illinois, and a one-time Cubs fans, he no longer followed the game. “I lived on the South Side and the Cubs were the North Side team, but I was a Cubs fan,” he says. “The only reason I really wanted to go after it was to be sure that we got it. There were two other groups looking for a team; I wasn’t sure they could get the job done.”

* * *

The expansion committee liked Huizenga instantly. They wondered aloud, did he plan to take on partners?

“My answer was that I preferred to do it alone,” Huizenga says. “If they wanted me to take in a partner, one from Dade County, one from Palm Beach, I would have considered that. Their response was, ‘No, we like the fact you’re going alone.’ That made me feel good.”

Weather wasn’t as easily dismissed. Huizenga acknowledged rain as a potential problem, but told the committee the harsh South Florida rains usually came in the afternoon, ending by 7 p.m. “There will be those times it doesn’t,” he told the committee. “We will have rain-outs, no question about it. We’ll just have to figure out how to make those up on days off.”

* * *

Huizenga’s attitude toward the expansion process foresaw a win-win-win situation for himself and Joe Robbie Stadium:

1) He might be selected to purchase an expansion franchise that would play 81 games at JRS.

2) Someone else from South Florida could be chosen and be convinced to play at least their first few seasons at JRS.

“On the one hand, we had a facility, such as it was,” Huizenga says. “But remember, it was a multipurpose facility. Baseball said, ‘We would prefer to have baseball-only, open-air, grass.’ The mayor of Miami said, ‘We’ll build that facility, well build it right down here on the bay.’ We thought the other guys may have had the inside track.

“[The Schmidt/Horrow group] said, ‘We’ll decide where to put the team after we get it.’ They figured they’d sign a lease with us once they got a team. And then maybe they’d build [their own stadium] five years later. You see, the other two groups knew we were spending the money to remodel our facility to get it ready for baseball. So if we didn’t get baseball, it would only make sense for us to lease them the stadium for a couple years, even if they were going to build their own facility. And we could recover some of our investment.”

3) Tampa Bay would host the only team in Florida, but in doing so would make South Florida number one in line for relocation of an existing team.

“That was our game plan from day one,” Huizenga says. “We assessed what would happen from reading the newspaper reports and listening to all the people that had been in this thing a long time. St. Petersburg had been in this a long time, Buffalo had been in this a long time. Denver — it seemed obvious that somebody felt obligated to put one out in the western part of the country rather than two more in the eastern part. There happened to be this time zone without a baseball team and whether that meant anything or not I didn’t know but everybody was making a big deal out of it. I felt that politically, Denver was going to get a team.

“I figured St. Petersburg would get a team,” he says. “And with the economics of baseball, some of the small market [teams] had to be sold. Carl and I had a conversation about small markets in big trouble and that people didn’t really realize the trouble they were in. Some teams make money, but a lot of teams don’t make money. It’s pretty bad for that guy at the bottom of the barrel. The bottom is in deep trouble.”

* * *

Once Huizenga made the National League owners’ short list in December 1990 to represent South Florida against Tampa Bay, Orlando, Washington, D.C., Buffalo and Denver in the battle for an expansion franchise, he became the pack’s front-runner, surprising even himself.

Tampa Bay, which had pursued a team for 14 years, found itself in the unaccustomed position of playing second fiddle to South Florida and Huizenga. Although the Tampa Bay area — and its two daily newspapers — didn’t take Orlando, Buffalo or Washington, D.C., very seriously, South Florida was a different threat entirely. It was a genuine metropolis, urbane, sophisticated and international; everything Tampa Bay dreamed of being.

H. Wayne Huizenga

Tampa Bay baseball fans, already thrown a curve when baseball picked Stephen Porter’s group to represent the region over hometown favorite Frank Morsani, shook their heads in dismay when “Captain Video,” Huizenga, paid Morsani $10,000 for the rights to use the name “Florida Panthers” if he were selected by the National League.

Unlike the battle of wits engaged between the Miami Herald ‘s Dave Barry and the Orlando Magic’s Pat Williams in 1989, the St. Petersburg Times and Tampa Tribune each went for H. Wayne Huizenga’s jugular. The slightest bit of controversy or bad news about Huizenga or Blockbuster Video — the Carl Barger connection, Blockbuster’s business dealings with Phoenix Communications and Major League Baseball — took on great significance. No matter how insignificant.

Huizenga denied that Blockbuster Video’s five-year exclusive deal with Phoenix Communications to sell licensed Major League Baseball videos improved his chances with the owners. Blockbuster also became a sponsor of national baseball telecasts in 1990.

And Huizenga’s 20-year personal friendship with Pittsburgh Pirates president Barger rocked the boat, too.

“All the bad stuff came out of Tampa/St. Petersburg,” Huizenga says. “Those guys did not get all their facts. They wrote from their emotions rather than from the facts. Okay, fine, they can write what they want to write. But they had Carl Barger influencing Danforth. I mean, not in a million years could that happen. You gotta know Doug Danforth. He’s chairman and CEO of Westinghouse. He was used to getting pressure all his life from people — ‘I need this, I want that.’ Doug Danforth was one of the leading CEOs ever in this country. He was not going to let somebody else make up his mind. Plus, it is not only the expansion committee that makes the decision. The ownership has got to vote. To think that Carl Barger, one guy, who’s not even an owner, just a president, an employee — to think that one employee on one team could go around and influence 26 owners — there was no way that could happen. Baseball guys couldn’t care less what some general manager or president tells them. Plus, it worked just the opposite for us, because Danforth was reading these same newspaper stories and he ended up keeping this thing at arm’s length. The other guys [Fred Wilpon, Bill Giles and Bill White] were friendly. They talked to me, they talked to Denver, they talked to St. Petersburg. But because Doug was worried about the perception, he wouldn’t even return phone calls.”

Barger wasn’t Huizenga’s only friend in the National League. Tom O’Donnell, president and publisher of the Fort Lauderdale-based Sun-Sentinel newspaper, which is owned by The Tribune Co., parent of the Chicago Cubs, introduced the Blockbuster Video boss to Stan Cook, president of the Cubs.

Huizenga dealt with expansion by deliberately keeping a low profile. He avoided the media as much as possible, concentrating on Blockbuster and his other businesses. He also steered clear of most rallies and other baseball events.

“You could have the whole community 100 percent behind you but the community doesn’t vote. Only the owners vote,” he says. “What’s the point of spending all your time and effort preaching to the choir?”

* * *

There remains considerable speculation that Huizenga was told early on he would receive one of the two franchises and that’s why he confidently invested $10-million out-of-pocket to convert JRS from football-only into a baseball stadium.

“The conjecture fits with what most people thought to be the economic decision analysis,” Miami Mayor Xavier Suarez says. “Anybody spending $10-million, plus a $100,000 application fee, probably had to expect the outcome. He had a very good idea that he fit the parameters of what they were looking for. But I lost my bet. I thought he’d begin work and not follow through. I didn’t see a lot of back-up use for all that [construction] without a baseball team.”

When Joe Robbie gave Huizenga his pitch about baseball in JRS, he showed the video magnate a model of the stadium in which the left field seats were removable for baseball. Unfortunately, Robbie had built left field with permanent seats, not knowing when or if baseball would ever come. Huizenga, once he owned a 50 percent interest in the stadium, decided JRS would be a whole lot more convincing as a baseball venue if the movable seats were in place.

“It’s difficult to take someone to the stadium and you look out there and you see the goal posts and say, ‘Just picture those left field seats coming out.’ Well,” he recalls, “somewhere along the way, we decided — ‘Why don’t we just spend the money and do it.’ “

Huizenga calls it “a roll of the dice,” but Ric Green, the Broward EDC’s sports director, says Huizenga would not spend $10-million on chance.

“Wayne Huizenga is a very smart businessman,” Green says. “He didn’t get where he is by not doing everything possible. He prepares 120 percent. I don’t want to claim the fix was in and I don’t want to cast any aspersions on Carl Barger. Everything that Wayne Huizenga could legitimately do I will guarantee you he attempted to do. His people over-prepare him for everything. I would imagine it would be foolish to not say he went to his good friend Carl Barger and said, ‘Who could I talk to?’ “

“I thought the team was going to St. Petersburg,” Huizenga says. “I thought that [converting JRS for baseball] was a long-term decision. Sooner or later we would get a team. Let’s say disaster happens somewhere, there was a fire in a stadium, an earthquake, and all of a sudden someone has to move. They’re going to have to have a place to go. The stadium in St. Petersburg is booked, because I figured St. Petersburg was going to get the team. So where else are you going to play? We’d be ready. Or if you wanted to buy a team and you could get permission to move it, okay, fine, you better do it quick. You wouldn’t want to buy a team and play in a town for two years saying, ‘We’re going to move two years from now.’ That wouldn’t work.”

As usual, Huizenga’s roll of the dice turned up lucky. Two hastily arranged exhibition games in late spring brought out 125,013 fans to JRS, a show of community support that backed up Huizenga’s open wallet. The numbers spoke for themselves.

Huizenga says the exhibition games let South Florida fans sent a message to Major League Baseball. And baseball heard them, loud and clear.

The spring games came after a bilingual, multicountry campaign to drum up support, including petition drives from Panama to Brazil, Key West to the Dominican Republic.

Volunteers inundated local sports agencies, offering to do anything they could do to help. A group called Baseball Maniacs formed in Fort Lauderdale. Pep rallies were held at the Bayside marketplace in downtown Miami. Sports bars across South Florida participated. So did the Cuban and Latin communities.

Suarez did everything he could — both as mayor and baseball fan. “One time I was watching ‘This Week in Baseball,’ “ he recalls. “They had a segment on broadcasting baseball games in Latin America. I sent copies of that segment to the expansion committee. I tried to convey that this would be very important for Major League Baseball. Forget Miami — this would be a stage to the world, I told them.”

Through the first few months of 1991, Huizenga says he understood South Florida to be running second to Tampa Bay in the minds of the expansion committee. “Everybody knew the Kohls had lots of money,” he says. “And everybody told me [Roy] Disney was in that deal. I don’t know if he was or not. But I kept seeing the propaganda out of Tampa, that their group’s net worth was a billion-five or something. And the guy in Orlando [Richard DeVos], he was a heavy hitter, worth a billion or so. So we weren’t the heavy guy in the pot, that’s for sure. I figured, we’ve got to keep plugging away and do our thing, see what happens.”

In late May, something happened to Huizenga, something painful. Despite explosive store growth and impressive earnings, Blockbuster’s stock tanked, dropping from $14.50 to $8.87 a share in nine weeks. Huizenga personally lost $115-million on paper, about the cost of a National League expansion franchise — not including players.

The Tampa Bay and Orlando media purred as it lapped up the bad news, making a final attempt to pump up local efforts for one last push. But Huizenga addressed investor concerns about his company’s future, convincing Wall Street it had panicked. Slowly, the price edged back up and Huizenga earned back $40-million of his loss.

Maybe Wall Street lost faith temporarily in the video star — but baseball didn’t. Rumors flew that Huizenga was in.

“I started getting phone calls saying, ‘Hey, I hear you guys are looking good,’ “ Huizenga recalls. “It might be an acquaintance. Or I might go to Wall Street on Blockbuster business and I’d bump into some guy and he’d say, ‘I was with somebody the other day who works over at the Mets or the Yankees and the word around there is you guys are looking good.’ Well, you don’t put much credit to something like that. When you stop and think that that’s some third-level person in the Yankees organization — they don’t know anything. But then a couple days would go by and I’d hear the same rumor two or three times and I’d say, ‘Whew, there’s too many rumors.’ “

* * *

Guys like Ric Green, the Broward EDC’s sports director, and his counterpart, Bill Perry III, executive director of the Miami Sports and Exhibition Authority, were easier to reach than Huizenga and his lieutenants. So they heard all the latest rumors.

Outrageous rumors had it that Huizenga made a deal with (University of Miami baseball coach) Ron Fraser to be his general manager, Green recalls. “They said he offered Blockbuster Video franchises to Bill White. Friends and reporters called me with this stuff. He was going to build a brand new stadium. He offered to put a dome on the stadium. Not one person was reliable. There was an article in [the failed sports daily] The National. They interviewed Mike Veeck — Bill Veeck’s son — who has a Florida State League franchise [The Miracle]. Mike was closely tied into this whole process because he owned the team that had the local baseball rights. Mike talked about how baseball will love South Florida. I told [Huizenga assistant] Don Smiley, ‘This is a great article, wouldn’t you say?’ and he said, ‘No, I hate it because baseball owners hate Bill Veeck.’ Oh, shit. Here you think you got some good publicity and … Oh boy.”

* * *

Anyone living in or visiting South Florida in May 1991 that didn’t know the region had a chance to get a baseball team must have had his head in the sand. The anticipation was palpable.

Instead of wondering where the two expansion teams would be placed, the question became who would be number two to South Florida. Would baseball place two new teams in Florida — with Tampa Bay second — or would it go with geographic diversity and make its second pitch to Denver?

“By the end of the whole process, everybody was saying South Florida didn’t have any weaknesses,” Mayor Suarez says. “I spoke to Doug Danforth and he said South Florida sounded good to him.”

* * *

All of the national baseball columnists weighed in with opinions on who would receive the two National League expansion franchises, all based on inside sources and educated guesses.

• Sports Illustrated announced Miami and Tampa Bay were a 1-2 punch for expansion.

• USA Today conducted two polls, one of a six-member professional panel, the other a survey of readers. Denver topped both polls as the No. 1 pick. The panel picked Miami as No. 2; readers chose Washington, D.C. One of the national newspaper’s panel members, baseball consultant Peter Bavasi, picked Tampa Bay and Miami.

• USA Today baseball writer Hal Bodley went with Denver and Miami.

• The Sporting News did a three-part study of the potential expansion cities. “If The Sporting News were picking the two expansion teams,” Paul Attner wrote, “they’d go to Miami and St. Petersburg. But if baseball decides to put only one club in Florida, Washington should get the second. What will baseball do? Pick St. Petersburg and Denver. And they better pray Denver can survive.”

• ESPN’s Peter Gammons first guessed St. Petersburg and Washington, D.C., then switched to Miami and St. Petersburg.

• Las Vegas oddsmakers listed St. Petersburg as a 1-5 favorite, Miami at 2-1, Denver at 4-1, Orlando and Washington, D.C. at 8-1 and Buffalo at 20-1.

• Sen. Tim Wirth, D-Colorado, chairman of the U.S. Senate task force on baseball expansion, said he received information indicating teams would be awarded to St. Petersburg and Denver.

• New York Daily News columnist Bill Madden wrote that Miami would beat out Tampa Bay due to a larger TV market and a single local owner. He foresaw the second team going to Denver.

• The Rocky Mountain News and Denver Post separately polled active ballplayers to learn which cities they preferred to see receive teams. Tampa Bay came out on top, followed by Denver, in both polls. Miami finished third in the polls.

• Baseball America columnist Tracy Ringolsby wrote, “Miami has made the strongest push at the finish to land a team, but St. Petersburg is the emotional favorite. The folks there put their money where their mouth is, building the stadium to prove a commitment. . . . Each time, the Florida folks accepted their role as patsy without causing legal headaches for Major League Baseball. Loyalty says it’s time to repay the kindness and give the folks the baseball team they have wanted for so long.”

* * *

“It’s a big mistake, I think, for baseball to expand. What they should do is let some of the weaker teams move to bigger cities. That’s not what the fans want to hear, but the economics of baseball have gotten so cattywonkus that the small towns can’t make it. Those teams are going to have to do something. That’s why I think St. Petersburg will get a team pretty soon.”

— H. Wayne Huizenga, Chairman of the Board, Blockbuster Video, Florida Marlins

The Florida Marlins and Colorado Rockies were born on June 10, 1991 — two days earlier than anticipated — dashing Tampa Bay’s hopes once again.

H. Wayne Huizenga — who paid Tampa’s Frank Morsani $10,000 for the rights to the name “Florida Panthers” but didn’t use it — told reporters he chose the statewide name “Florida Marlins” to take advantage of being the first baseball team in Florida.

His first major hiring decision as a team owner didn’t please or surprise Tampa Bay fans who felt the “fix” was in from the start: Carl Barger, Blockbuster Entertainment board member and president of the Pittsburgh Pirates, agreed to move south and take the helm of the Marlins.

“That didn’t seem to pass the smell test,” Porter group investor Mark Bostick says.

South Florida — which couldn’t care less what Bostick thought — fell at Huizenga the Conqueror’s feet.

“The baseball owners are very much like a club,” Miami Mayor Xavier Suarez says. “Huizenga was ideal for them. He was a very likable guy, low-key and soft-spoken. He was the kind of guy who would not come blustering into meetings, would not be too aggressive. And he put his money where his mouth was.”

* * *

(Missing out on expansion, St. Petersburg still refused to give up. The city began courting the financially troubled Seattle Mariners, a team frustrated by low attendance and miniscule media revenues.)

* * *

At the 1991 baseball winter meetings in Miami Beach, St. Petersburg assistant city manager Rick Dodge learned that winning an expansion team did not make a good sport out of Florida Marlins chairman H. Wayne Huizenga when it came to the neverending talk of a team relocating to St. Petersburg.

Not over my dead video rewinder, Huizenga told fellow team owners in a private meeting.

Huizenga figured he beat St. Petersburg fair and square. (Never mind that he hired his pal, Pittsburgh Pirates president Carl Barger within days of being awarded the Marlins.) If he was going to plunk down a $95-million fee just to get into the National League and invest another $30-million to get an undoubtedly lousy team up and running, he wanted some guarantee of at least temporary exclusivity in Florida. It wasn’t going to be easy or cheap to build fan support those first few years; an established team that might relocate and start play in St. Petersburg in 1992 would steal the Marlins’ bait.

In December and January, the video king threatened to renege on his deal or sue baseball unless a team moving to St. Petersburg paid a compensatory territorial fee to him estimated at $15-million.

Didn’t take long for that declaration to leak to the press. Huizenga and Marlins president Carl Barger denied they made such demands but too many baseball insiders confirmed the story for it not to be close to the truth.

“We heard that he went to the commissioner and was very direct about it: ‘If you allow Seattle to come here, I am going to withdraw my deposit or sue baseball,’ “ Dodge says. “I heard this from a couple of different people. People who have been friendly to us in the NL, we saw them shifting to protect Huizenga’s supposed interest. We knew it was a serious issue.”

Barger was quoted as saying with regard to a possible Mariners relocation to St. Petersburg, “We’re not going to take this sitting down.”

He wasn’t the only one, either. Steve Ehrhart, president and chief operating officer of the Colorado Rockies, was equally pissed off. “There’s going to be hell to pay on this,” he told the Tampa Tribune’s Joe Henderson. “Jeff thinks he can just come in there in a great market and line his pockets . . . while the rest of us are struggling. Well, he can’t have his cake and eat it too . . . We were prohibited from dealing with Seattle before we got this team, and we did inquire. We could have bought the Mariners for a lot less than we paid for this.”

Huizenga had every right to protect his interests. And baseball owners greedily clung to their individual shares of the video king’s expected cash contribution, afraid to contradict this powerful rookie member of the club. But Tampa Bay civic, political and sports leaders kicked up a fury. Screw you, H. Wayne, and the remote control you rode in on. Campaigns to boycott the Tampa Bay area Blockbuster Video stores were plotted. The Hillsborough and Pinellas county legislative delegations looked at ways of punishing Huizenga and Joe Robbie Stadium through legislation. And the bad publicity caromed across the country.

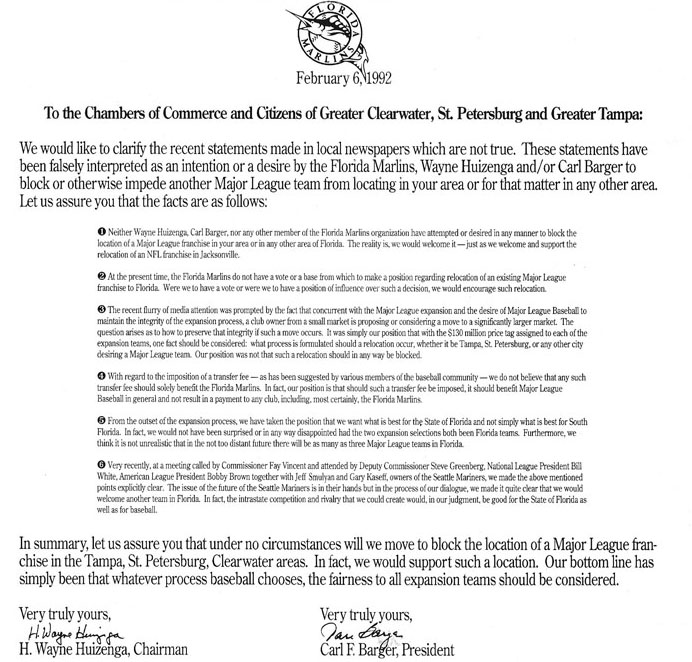

Although it’s doubtful they truly had a change of heart, Huizenga and Barger held a press conference at the Florida Suncoast Dome February 7 and bought newspaper ads in the St. Petersburg Times and Tampa Tribune to clarify their position.

“We spoke that day independent of the press conference,” Jack Critchfield recalls, “a personal, man-to-man reiteration of what they were saying publicly. They understood that Tampa Bay was not part of their market, that there would be no reason for them to oppose a team here and, in fact, they hoped that Florida had at least one, if not two more. Mr. Huizenga had a genuine concern that he paid too much for the franchise. He is a good man, and his record in business had been one of integrity. What they did was in their best interest. I think they would never have opposed a franchise here had they known it would be public knowledge. The fact that it became public put them in an untenable position and they had to go out and mend fences. They were silent on the issue from that point forward.”

Dodge was less enamored of Huizenga than was Critchfield. He heard the video king’s words, he just didn’t believe him.

“Very impressive guy,” Dodge recalls. “He said that he wouldn’t object and wouldn’t stand in the way and that there may have been some misunderstandings, but it wouldn’t be that way in the future. We all kind of looked at each other. Right. Sure. You wanted to believe him but he raised the issue of Seattle in the commissioner’s eyes. [Before coming to St. Petersburg,] Barger or somebody claimed that Smulyan had met with us. That got Smulyan in trouble with the commissioner; In fact he got fined. Heavily. When he met with us we assumed Jeff had [the commissioner’s] permission. But he didn’t inform the American League or the commissioner. The commissioner fined him $100,000.”

Smulyan would neither confirm or deny the fine. But Barger was right: Smulyan had finally met face-to-face with representatives of the City of St. Petersburg.

* * *

( The Seattle Mariners were eventually sold to Nintendo of America, the Japanese video game manufacturer, and the team remained in the Pacific Northwest. Not long after the sale was approved, a press conference was held at the Florida Suncoast Dome to announced that a local group led by businessman Vincent Naimoli had an agreement in principle to purchase the San Francisco Giants and relocate the team to St. Petersburg.)

* * *

When it came right down to brass balls, only two factors decided the future of the San Francisco Giants: television revenues and H. Wayne Huizenga. In that order.

In 1992, baseball was not the hot broadcast property it was four years earlier, when the game’s owners signed a $1.06-billion, four-year deal with CBS-TV and a $250-million deal with ESPN. Ratings were down. The game moved too slowly and dragged on too long for an audience choosing between baseball, American Gladiators, Geraldo Rivera and The Simpsons. ESPN notified Major League Baseball late in the ‘92 season that it would not renew its option for 1994 and ‘95, buying out the contract for $13-million instead. And CBS — which tried to renegotiate its deal in 1992 — made it quite clear that while it might renegotiate a new broadcast contract for the ‘94 season, the price would be at least 25 percent less than the original deal.

The idea that baseball might allow a franchise to leave the No. 5 television market in the country, San Francisco, for the No. 13 market, Tampa Bay, was pure idiocy to CBS. The introduction of CBS executive (and San Francisco native) Larry Baer to the behind-the-scenes machinations of the San Francisco bid left no doubt from where the real power and influence of this deal came. It wasn’t Bob Lurie, Vince Naimoli, Mayor Frank Jordan, Walter Shorenstein or Bill White. Baseball was warned that a bonehead move of the Giants out of San Francisco could cause the ‘94 broadcast offer to be in the neighborhood of $500-million, or 50 percent less than the old deal. That’s power.

To a team, this could mean a per team, annual drop in national broadcast revenues from $5- to $10-million. Television was the financial villain in all of this. Not the baloney about baseball’s traditions and resistance to team relocation.

Further stirring the money pit was Captain Video.

In the final stages of the 1991 expansion derby, Huizenga was assured that if he paid out the $95-million franchise fee demanded by the National League, he would be guaranteed at least one year of exclusivity — no competition from another team in Florida. It was an important part of the deal for Huizenga, who understood the desperate need of an expansion franchise to be loved and cherished by as many people as possible in its first undistinguished seasons.

The first time Huizenga felt this promise might be broken, during the 1991 winter meetings, he told fellow baseball owners that if they moved the Seattle Mariners to Tampa Bay, they could kiss his $95-million goodbye. They caved in and bent over backward to structure the Nintendo of America bid that wrestled the Mariners away from a frustrated Jeff Smulyan.

When the Giants issue arose just weeks after the Mariners transfer was done, Huizenga’s political situation was more delicate than ever at home. A hero to South Florida, he was ill-considered in the central and northern reaches of the Sunshine State for his success in winning an expansion franchise at Tampa Bay’s expense, for the perception that he derailed the Mariners from the Florida Suncoast Dome, and for his two-headed handling of the Giants opportunity.

Publicly, Huizenga encouraged Bob Lurie to come to Florida even before Vince Naimoli made his first offer for the Giants. (“Not only would we not stand in the way, we sought him {Lurie} out and encouraged him to come,” Huizenga said.) Publicly, Huizenga talked about the dollars-and-cents value of an in-state rivalry. (“We are pleased for the fans in the Tampa Bay area and pleased that the team is in the National League. This will help in building a friendly cross-state rivalry.”) Publicly, Huizenga said all the right things.

Privately, Huizenga and Marlins President Carl Barger reportedly turned every screw they could think of to keep the fourth most populous state in the country to themselves. And every time they howled with indignation at the charge of backstabbing, an owner called Rick Dodge, Jack Critchfield or Vince Naimoli to reconfirm that the Marlins were indeed lobbying opposition to the Giants deal.

“I had a lot of theories,” Dodge says, “but I heard often enough that Wayne Huizenga said he was promised an ‘exclusive’ to Florida for a number of years. He is not going to say that and baseball is not going to say that because that is collusion. I think there was a promise made. I’ve heard it from enough people in baseball to believe it. If that’s true, that is a whole other issue. What we found inconsistent were things like Carl Barger saying he was surprised that Bob Lurie moved quickly on this deal without getting approval. Huizenga said, in advance of us going to San Francisco, that he had called Bob Lurie and invited him to move the franchise. It was real simple. They wanted to protect their exclusivity as long as they could and they didn’t want to have an experienced, powerful club in the same state to compete against. They also wanted to see this market eventually have to pay an expansion fee that the Marlins could share.”

Critchfield wanted to believe Huizenga. He had met the man, discussed matters with him face to face and he truly hoped Huizenga was being straight with him. Wouldn’t an in-state rivalry help the Marlins? Wouldn’t Huizenga save on travel expenses by a relocation of the Giants to the Tampa Bay area?

“He stated clearly that if a vote came they would vote for it,” Critchfield says. “What he left unsaid was that they certainly would have liked to see that there was never a vote. They wanted at least one year before they had any competition in Florida. I couldn’t get inside Mr Huizenga’s mind. It was unfortunate that he gave the impression publicly and to me that they’d do nothing to resist relocation; in fact, there appeared to be evidence that they did. I tried to understand why. While I disagreed with the way he handled it, I suspect that if I were a new owner and if I realized that I paid far too much for a new franchise in a community that may or may not support it, with a stadium that probably needs a roof on it, and I lost even a million dollars of projected revenue, then I couldn’t be very happy about it. Especially if someone in baseball legally or illegally gave me reason to think that they would see to it that I had no competition. I was unhappy and I was disappointed it wasn’t handled better by the Marlins in general and that obviously is Mr. Huizenga.”

Huizenga made it no secret that he overpaid for the Marlins. And he resented anyone who might reduce his income by siphoning off media or other revenues, which was exactly what he feared a Tampa Bay franchise might do. But it was exactly that attitude that disquieted Tampa Bay partisans. Making matters tougher for Huizenga, he was unable to take that position public because much of the state of Florida — from the governor on down — didn’t believe that stonewalling a major economic opportunity for Tampa Bay meant operating in the best interest of the state.

Hard evidence of Huizenga’s alleged complicity was hard to come by, but rumor and innuendo were thick. St. Petersburg Times sportswriter Marc Topkin called it “the Energizer Bunny of rumors, because it keeps going and going and going.”

• “We didn’t get into this thing anticipating that we were going to have competition 250 miles away before we even threw out our first pitch,” Marlins President Carl Barger told Topkin.

• New York Daily News columnist Bill Madden reported that Huizenga “defected from the growing group of owners seeking to oust Fay Vincent after the commissioner promised he would use his ‘best-interests-of-baseball’ powers to block the move of the Giants to Tampa-St. Pete if the owners approved it.”

• The Miami Herald — another Huizenga-friendly daily — reported that the Marlins owner wanted to place his Triple A farm team in Charlotte, North Carolina. To do that, Huizenga flew to Charlotte in September and reached an agreement in principle with the man who owned the Class A Charlotte Knights and territorial rights — George Shinn. The deal would have put at least $1-million in Shinn’s wallet and an NL owner in his pocket at a time when he was negotiating to buy the Giants and keep them in San Francisco. But the baseball commissioner’s office nixed the deal, awarding the Triple A rights in Charlotte to the Cleveland Indians and banishing the Marlins’ top farm team to Edmonton, in western Canada.

• And in a curious move, Blockbuster Entertainment purchased 236 stores in the Sound Warehouse and Music Plus chains for $185-million. The seller? Shamrock Holdings, a firm controlled by Roy Disney, late of the unsuccessful Tampa Bay expansion group. To the business world, the transaction meant Blockbuster was simply diversifying. To Tampa Bay baseball fans, it portended something more sinister, such as a payoff for the apparent pullout of Disney’s cash from Steve Porter’s group in 1991.

Tampa Bay’s baseball fans reached the breaking point with Huizenga on October 22, 1992. Spurred on by WFLA radio talk show host Jay Marvin and organized by local resident Jim Cohen, 75 people protested Huizenga’s meddling by creating a scene in front of a Blockbuster Video store in St. Petersburg. They lined the sidewalk on Fourth Street N, waving an array of signs aimed at Huizenga: “This Ain’t Your World, Wayne!” “Just Say Yes, Wayne.” “No Support, No State $.” “Wayne is Being a Pain!” “Blockbuster Chairman is Against TB Giants.” “Hey, Wayne: Vote Yes on Tampa Bay Giants or No Videos!” “Shame On You Blockbuster!” And even one non-aligned sign: “Will Work for Season Tickets.”

Passing motorists honked their horns in support of the protesters, several of whom lined the store’s driveway entrance and pleaded with Blockbuster customers to turn in their rental cards. Many did.

Marlins President Carl Barger didn’t get the point.

“It’s getting a little old,” he told St. Petersburg Times reporter Tom Tobin. “Blockbuster is a publicly held company. Blockbuster has nothing to do with the Marlins just because Wayne Huizenga has an involvement. No one loves baseball more than I do {but} I think to take baseball to those extremes is kind of sad.”

A competitor of Blockbuster in St. Petersburg, Network Video, printed T-shirts to establish a distinction between the two companies: “Network Video supports baseball for Tampa Bay. The OTHER video store doesn’t!”

“If what we heard about Mr. Huizenga was untrue,” Dodge says, “he was the most maligned person inside baseball.”

The Party Authority in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware and Maryland!

The Party Authority in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware and Maryland!